Why is it so difficult for the U.S. to implement a wealth tax?

Share Now on:

Why is it so difficult for the U.S. to implement a wealth tax?

While the House has approved part of President Joe Biden’s domestic policy plan, the rest will have to wait as lawmakers wait to confirm how much it may cost.

On Friday, the House passed Biden’s $1 trillion infrastructure package, but postponed a vote on Biden’s social spending agenda, an estimated $1.8 trillion plan that would extend the child tax credit by one year, establish universal pre-Kindergarten and expand Medicaid.

The social spending plan, also known as Build Back Better, has already been pared down from its initial $3.5 trillion price tag and would span 10 years.

Lawmakers have proposed different ideas to pay for the president’s current plan, which include taxes that would target wealthy Americans and corporations. In late October, Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden from Oregon released one that would specifically go after the country’s very richest.

The Billionaires Income Tax plan would affect taxpayers with more than $1 billion in assets or more than $100 million in income for three consecutive years.

His plan would raise $557 billion over 10 years, according to preliminary estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation released on Friday. Although the plan was not included in the White House’s social-spending package framework, Wyden continues to tout the plan, stating that the JCT’s estimates show that “the tax code is simply not equipped to tax billionaires fairly, or ensure they pay any taxes at all.”

Under the plan, billionaires would have to pay taxes on the unrealized gains of tradable assets like stocks, and take yearly deductions for losses. They would be able to carry forward any losses, and in some cases, carry back losses for three years. When it comes to non-tradable assets like real estate, billionaires would have to pay capital gains tax, plus an interest charge.

Bridget Crawford, a law professor at Pace University, said the tax on unrealized gains works like this: “If I bought Microsoft for $1 a share, and it’s currently worth $10 a share, even though I haven’t sold it, the Wyden plan would tax me on $9 of gain. Current law says, ‘Well, Bridget Crawford doesn’t get taxed until she actually sells it.’”

More than 100 national organizations, including Americans for Tax Fairness and Health Care for America Now, signed a letter in support of Wyden’s plan, saying that it would “end the scandal of tax-free billionaires by taxing their main source of income, the annual growth in their wealth.”

The demand for a wealth tax

In the U.S., there are now 745 billionaires who cumulatively hold $5 trillion in wealth, according to the Institute for Policy Studies and Americans for Tax Fairness.

Meanwhile, wealth inequality, which the pandemic put into stark relief, continues to grow. IPS and ATF said that billionaire wealth collectively grew by 70%, or $2.1 trillion during the pandemic, a period that saw record job losses and unemployment.

A majority of Americans, roughly two-thirds, say billionaires should pay a wealth tax, according to a poll from The Hill and Harris X.

Another poll, from the Pew Research Center, found that a growing number of U.S. adults disapprove of the fortunes of billionaires. About 30% of Americans during the summer said that billionaires are “a bad thing for the country,” up from a quarter of Americans in January 2020.

Frank Clemente, the executive director of Americans for Tax Fairness, said Wyden’s plan is calling for billionaires to pay taxes as their assets increase in value, because when you’re really rich, you don’t have to sell them.

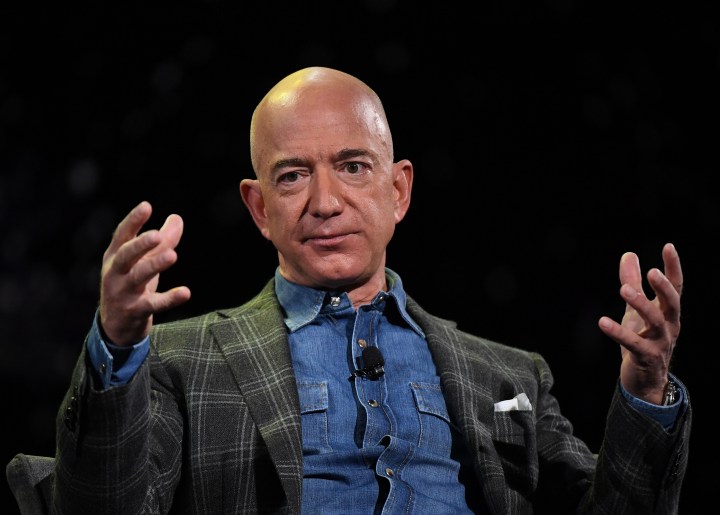

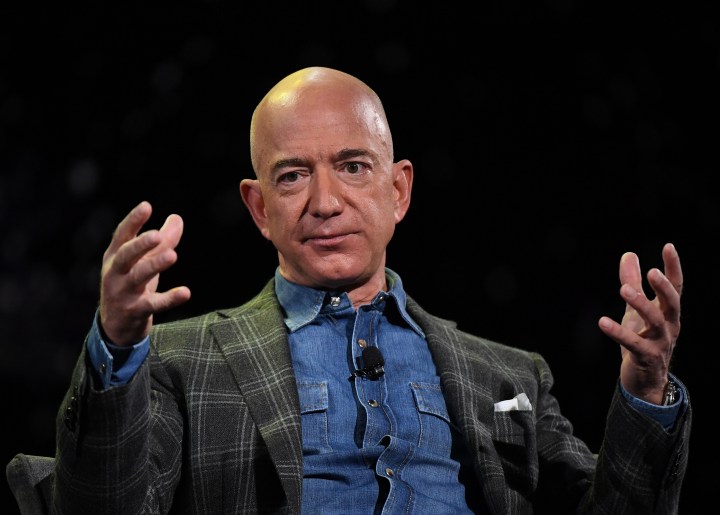

“If Jeff Bezos is getting paid $83,000 a year, but his stock value went up $20 billion that same year, unless he sells his stock, he’s only being taxed on the $83,000,” Clemente said.

Wyden’s plan isn’t the first wealth tax Democrats have proposed. Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, along with several other party members, introduced the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act earlier this year.

This plan would impose a 3% total annual tax on wealth above $1 billion, and a 2% annual tax on the net worth of households and trusts between $50 million and $1 billion.

The complications that come with wealth taxes

Despite support for a wealth tax, we’ve yet to see one come to fruition. Some experts say that it would be difficult to implement one effectively, both because of the U.S. tax code and because of lobbying efforts by the ultrawealthy.

Crawford of Pace University said a plan like Wyden’s is “administratively complex and easy to evade.” She added that taxing unrealized gains assumes that stock values tend to increase.

“Well, what if the value of the stock actually goes down in the next year? I sold it for a loss. So there would be a tremendous amount of paperwork associated with this accounting. I would have to take a snapshot every year of my portfolio,” she said. “Can it be done? Yes, of course. But it is not the way the U.S. system is set up.”

She pointed out that an “understaffed and under-informed IRS” would be tasked with carrying out this law.

Crawford added that Florida had an intangible tax that took a snapshot of a person’s assets on a particular date. She explained this encourages strategic behavior since some people give their assets away that day, only to get them back the next day.

Steve Utke, an associate professor of accounting at the University of Connecticut, also said it would be tricky to value non-marketable securities, which can’t be traded on a public exchange, like artwork or your family business.

He said this raises questions over who should appraise it — if billionaires are employing their own, the appraiser has an incentive to be favorable to him or her.

When it comes to plans such as Warren’s wealth tax, Crawford said she thinks that it would be held up in litigation over its constitutionality, even though she personally believes it “passes constitutional muster.”

The constitutional argument against it is that direct taxes have to be apportioned based on a state’s population, Crawford explained. So if a state has 15% of the population, then 15% of a direct tax’s revenue has to come from that state. “Direct taxes” is the key phrase here, and legal experts have argued that Warren’s wealth tax would be considered one.

“It is easy to say that one is anti-wealth concentration. The rhetoric is easy to get behind. The reality is much more complicated,” Crawford said.

Utke pointed out that several European countries have tried wealth taxes throughout the years, only to dispense of them later on.

Revenues generated from these wealth taxes are generally very low, which was one of the justifications for their repeal, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

To remedy wealth inequality, Crawford said that instead, the estate and gift tax exemption should decrease to Obama-era levels.

The Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 doubled the exemption amount from $5.49 million per individual to $11.8 million. What this means is that you’re allowed to transfer this amount of wealth without facing a 40% tax. In 2009, the estate tax exemption stood much lower at $3.5 million per person, while the gift tax stood at $1 million per person. The maximum tax rates on amounts above both of these thresholds stood at 45%.

She also said the U.S. should implement a carryover basis regime, which has been enacted into law before. Because of lenient rules surrounding capital gains on inherited property in our current system, people who sell theirs aren’t taxed as much as they would be under a carryover system.

“It’s working within the current system that people know and expect,” Crawford said. “And it’s merely reverting back to laws that have been implemented before. There’s a blueprint on how they work.”

But Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, economists who helped Warren develop her own proposal, have been vocal that one could work. When it comes to the failure of the European Union’s wealth taxes, for example, they’ve written that these taxes had “myriad exemptions, deductions and other breaks,” and pointed out that the EU tolerates tax competition among member states in the European and “tax evasion to a foolish degree.”

In an interview earlier this year with Marketplace, Warren said we would already have implemented a wealth tax if the super wealthy hadn’t expended resources lobbying against one.

“Billionaires and super millionaires talk a lot louder in Washington than everyone else. They make a lot more campaign contributions. They hire a lot more lobbyists,” she said. “They finance a lot more think tanks. And they make it really tough for some folks in Washington to think about a 2-cent wealth tax on their great fortunes.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.