Is this ‘full employment’ yet?

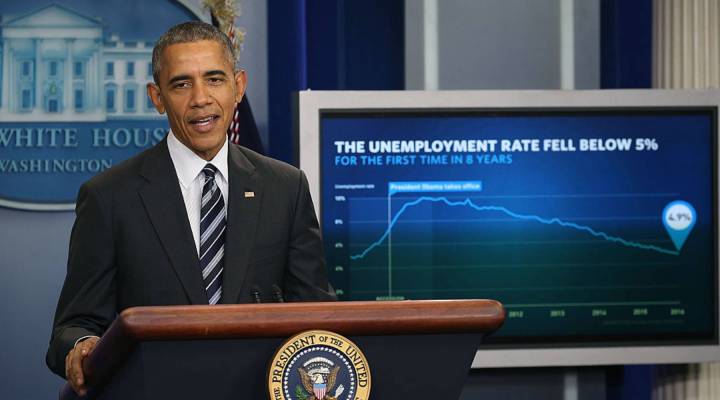

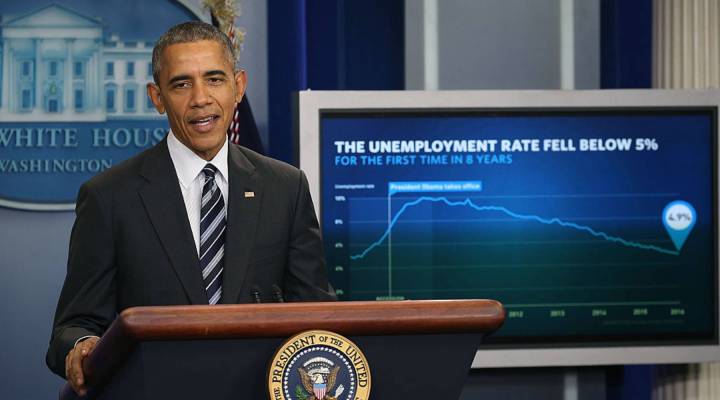

January’s employment report from the Labor Department was a mixed bag.

Here are the key takeaways:

- -Job gain of 151,000, below economists’ expectation of approximately 190,000. Also well below the 283,000 per month average rate of job creation for the last quarter of 2015.

- -The unemployment rate fell 0.1 percent to 4.9 percent, the lowest level since February 2008.

- -The labor force increased by approximately 500,000; Labor Force Participation Rate rose 0.1 percent to 62.7 percent.

- -Average hourly wages rose $0.12, or 0.5 percent in January, compared to 0.0 percent change in December. Hourly earnings rose 2.5 percent year-over-year, before adjusting for inflation.

- -Job sectors that increased employment included manufacturing (29,000), retail (58,000), health care (37,000), food and drinking establishments (47,000) and financial services (18,000).

- -There were job losses in federal and state government, education, mining — particularly oil and gas — and temporary help.

At 4.9 percent unemployment, the economy is now in a zone that many economists and Fed governors would consider “full employment.” The technical term is “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment,” or NAIRU. It’s a point of equilibrium where most workers can find the jobs they want and are qualified for, and most employers can find the workers they need. With full employment, wages tend to rise steadily, as employers increase the incentives they offer (pay, benefits, and other accommodations, such as flexible scheduling) to attract and retain the workers they need. Workers, meanwhile, feel reasonably confident that they will find new jobs if they quit voluntarily to seek better opportunities.

Full employment does not mean that every person who wants a job has one. There’s always churn — labor-market friction, with people switching jobs — as well as structural mis-matches — unskilled workers or those with poor work histories who have trouble finding anything, and positions requiring specific skills or credentials that employers have trouble filling.

But on balance, full employment means “people who have the skills and want to work are able to get a job,” said Dean Baker at the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Economist Aparna Mathur at the American Enterprise Institute said at this point — even with baseline unemployment at 4.9 percent — there is too much slack in the labor market to meet Baker’s definition.

“We know there are about 6 million people who are still saying, ‘We are involuntary part-time employed. We would prefer to have full-time jobs, but we’re just not finding them,’” said Mathur. She also pointed to historically-high levels of long-term unemployment (compared to other recession-recovery cycles prior to the Great Recession), teen and minority unemployment, discouraged workers and those who have dropped out of the labor force altogether.

“What we really want is all these people who are looking for jobs, to find jobs,” Mathur said. “And that will really start showing up in the wage data.”

At “full employment,” or NAIRU, standard economic theory predicts that employers will have to raise pay to attract and retain the workers they need. If the unemployment rate dips significantly below that level, economists begin to worry about distortions emerging in the economy, with severe labor shortages driving accelerating wage inflation, which in turn drives consumer price inflation higher in a way that can be difficult to control.

The last time the U.S. economy hit an ideal balance of employment, unemployment, real wage increases and manageable price inflation was the end of the 1990s economic boom, in late 2000, when unemployment fell below 4.0 percent, Baker said.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.