What Amazon’s union battle in Alabama means for workers

Share Now on:

What Amazon’s union battle in Alabama means for workers

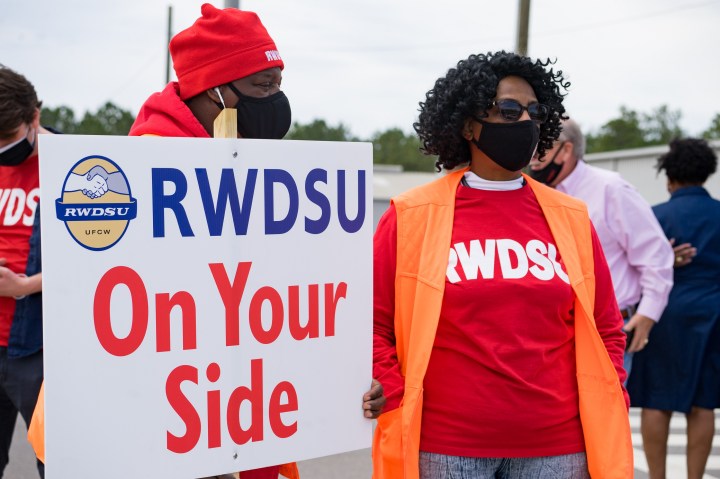

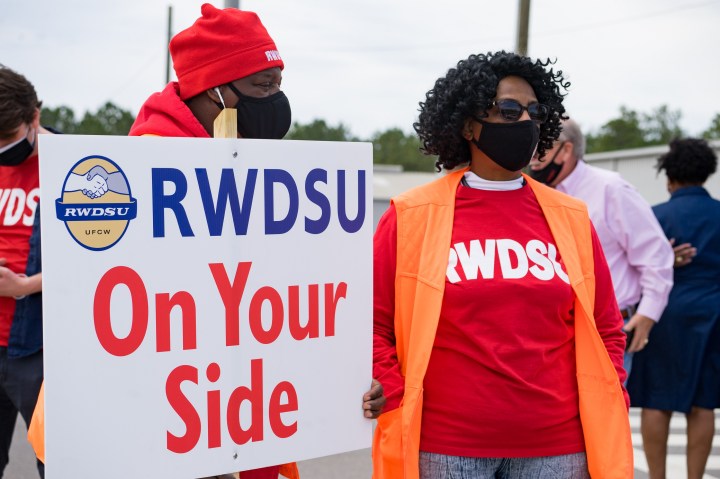

Workers at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, have until March 29 to vote on whether to unionize, a decision that could represent a significant victory for the U.S. labor movement.

Nearly 6,000 workers will decide if they want to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. A majority yes vote would make Bessemer the first Amazon warehouse to unionize.

On Wednesday, the Senate Budget Committee held a hearing on income inequality, which included testimony from Bessemer employee Jennifer Bates on why workers are organizing.

“We do it because we hope, with a union, we will finally have a level playing field. We hope we will be able to talk to someone at [human resources] without being dismissed. We hope that we will be able to rest more,” Bates said. “We’re hoping we get a living wage — not just Amazon’s minimum wage — and be able to provide better for our families.”

Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos declined an invitation from Sen. Bernie Sanders to testify.

The company has used its wage levels, which currently start at $15 an hour, as a selling point to discourage unionization. In Bessemer, workers told the Guardian website that Amazon has held anti-union meetings and used intimidation tactics.

Amazon, in response to Marketplace’s request for comment, said: “It is important that all employees understand the facts of joining a union and the election process. We hosted regular information sessions for all employees, which include an opportunity for employees to ask questions.”

Joseph Slater, a law professor at the University of Toledo, said a victory could encourage workers at other Amazon plants to unionize.

“It’d be symbolic both in terms of taking on a huge international employer, and in terms of being a successful organizing attempt in [the South] — a part of the country that has not seen that many successful union organizing attempts,” Slater said.

Employees who have attempted to unionize in the past have allegedly faced retaliation from the retail giant. In 2019, the company fired an employee who led unionization efforts in Staten Island, New York, and had been outspoken about working conditions. Amazon has denied the accusations.

Slater said that unions would be able to help workers at organizations like Amazon feel protected when they bring up day-to-day issues — like assembly lines moving too quickly or unfair break policies.

“One of the things that unions do is that they are a mechanism by which the people who actually do the work can give their opinions about how the work can be done better,” he said.

Ruth Milkman, a labor sociologist at the City University of New York, pointed out that one of the main objectives in these organizing efforts is to give workers a voice without fear of retaliation.

“The opportunity to speak without fear about whatever concerns you have in the workplace is just as important as the economic benefits that come with unionization,” Milkman said.

The Brookings Institution noted that Black workers have been overrepresented on the COVID-19 front lines. Last October, Amazon disclosed that almost 20,000 workers had been infected.

Black workers make up 27% of Amazon’s workforce (compared to 13% of workers overall in the U.S.). At the Bessemer warehouse, union organizers estimate that 85% of workers are Black.

Slater said that in the event of a victory, he thinks Amazon would recognize the union fairly quickly, but the bargaining process could take a while.

“The main legal consequence of a union being recognized is that the employer now has, what is called in labor law, a duty to bargain in good faith with the union to try to form a contract,” Slater said. But according to the Economic Policy Institute, employers can end up stalling the first union contract for years, and some unions never obtain one.

Washington has weighed in on the labor battle, with lawmakers from both parties expressing solidarity with the Amazon workers. Republican Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida penned an op-ed last week that argued “Amazon has waged a war against working-class values,” while Sanders, a Vermont Democrat, said Bezos “must not interfere in this election.”

And President Joe Biden — whose campaign website listed strengthening public- and private-sector unions as a priority — recently tweeted that “every worker should have a free and fair choice to join a union.”

“Unions built the middle class. Unions put power in the hands of workers. They level the playing field. They give you a stronger voice for your health, your safety, higher wages, protections from racial discrimination and sexual harassment,” Biden said in a video.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.