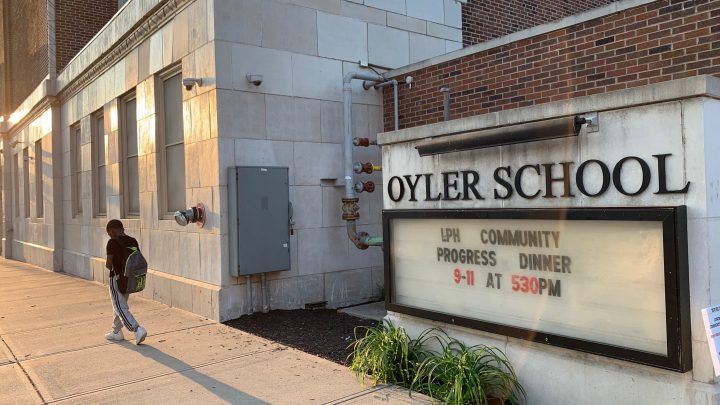

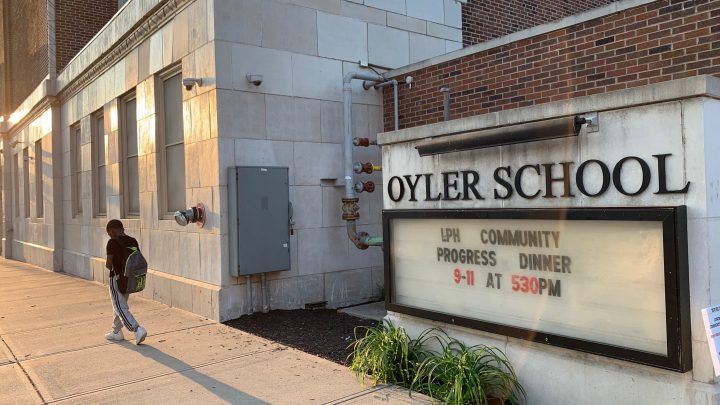

Cincinnati’s Oyler School tries to rebuild its neighborhood

Cincinnati’s Oyler School tries to rebuild its neighborhood

Jami Luggen’s office at Cincinnati’s Oyler School is stacked floor to ceiling with plastic bins full of backpacks, school supplies, deodorant and shampoo. A few sparkly prom dresses hang from the coat rack by the door.

“Things that I know we need at the last second,” she said. “A kid’s leaving, ‘Oh Ms. Jami, I’ve lost my gloves and my hat, can you make sure I have that?’”

Usually, she can. Oyler is known as a community learning center, founded on the philosophy that a school is only as successful as its neighborhood. Luggen is the resource coordinator, and it’s her job to connect students and their families with everything from the school’s wide array of health and social services to an extra pair of gym socks. But about five years ago, kids started coming to her for something she couldn’t stock on her shelves: a place to spend the night.

“It started out with a lot of high school kids that were, for whatever reason, homeless,” she said. “And they would have nowhere to go.”

So she worked the phones, calling shelters, finding other parents to take kids in — even sometimes bringing students home with her. “Then it got to the point where we had so many kids, I felt like my entire time was trying to find places for students to live,” she said.

Oyler had run up against a hard reality: that transforming a school — even on the grand scale that Oyler had been transformed — may not be enough to spark the transformation of the surrounding neighborhood.

Oyler is in Lower Price Hill, one of Cincinnati’s poorest areas. Oyler used to be a K-8 school, and very few of its students went on to finish high school. But in 2006, with a mix of public and private funding, Oyler added a high school, along with a health center and counseling services. The school completed a $21 million renovation in 2012, eventually adding vision and dental clinics, a food pantry and free clothing store. Standardized test scores have continued to lag, but Oyler’s graduation rate has steadily ticked up to a high of 85% last year.

“We had some hope that if the school was itself an attraction to people to come to the neighborhood, that the neighborhood would kind of organically improve,” said Darlene Kamine, who helped lead the turnaround as founder of the Community Learning Center Institute. “But the housing stock and the community was so distressed that it just couldn’t happen quite in that organic way.”

The next step was to rebuild that community.

At the end of a school day, Kimmi Washburn waved her last preschooler out the door before clocking out. In some ways, Washburn is the embodiment of Oyler’s progress. After having a baby at 17, she was in the second class to graduate from the high school. She got an associate’s degree and became an assistant teacher. Her daughter is a fourth grader at Oyler. And Washburn, 26, is about to become a homeowner.

A few blocks from the school, Habitat for Humanity staff and volunteers are renovating a three-story brick house built in the 1880s, one of seven vacant homes the group has bought in Lower Price Hill. To qualify to buy the house, Washburn had to take classes in personal finance and home maintenance. Almost every Saturday since February, she’s joined the crew, helping install insulation and paint walls.

“When I stop being so sore, I love it,” she said. “But I have to earn sweat equity.”

The Habitat homes are part of a much bigger plan to revitalize Lower Price Hill, led by Adelyn Hall, the Community Learning Center Institute’s first director of housing and neighborhood development. She was brought on in 2015 to help stem the housing crisis.

“If you don’t have a home, there’s so many things that you cannot be successful at, education being one of them,” she said. Step one was partnering with city agencies and nonprofits to make sure kids had a safe place to sleep every night. Step two was working with developers, landlords and local businesses to create long-term stability.

School staff, community leaders and residents packed the Oyler cafeteria last month for an update on the plan. Thirty-four million dollars have been committed so far to rehab 130 units of rental housing, add trees, lighting, a new riverfront park and more.

Tameca Ballard-Thomas recently moved into another Habitat for Humanity house and came to the meeting to see how she might pitch in.

“I want to help with the green space and the neighborhood watch and whatever,” she said. “I’m just jumping in because I’m vested now. I’m here. I have property here.”

Back at her future house, Washburn put on a hard hat and walked through her future kitchen.

“I have two Lazy Susans,” she said, spinning a tray inside a cabinet. “I’m thinking one for bakeware and one for pots and pans.”

It’s a big upgrade from the Section 8 apartment she’s been renting a few doors down. She and her boyfriend share a bedroom with their daughter Haylee. For a while, Washburn did their laundry in the bathtub.

“There used to be prostitutes in the building,” she said. “So before, the building basement got locked up and you had to have a certain key for it.”

When the new house is finished later this fall, Washburn will take out a zero-interest mortgage from Habitat and pay just $500 a month. It’s only a little more than she’s been paying for her cramped apartment. Within a few years, the plan is to double the homeownership rate in Lower Price Hill.

“Maybe there will be less pollution because we’ll all have our own garbage can,” Washburn said. “Maybe more families actually care about being parents to their children. Less stress, more positivity, more Oyler graduates.”

That’s the idea. Children with stable housing tend to do better in school and are much more likely to graduate.

Of course, just renovating blighted buildings and moving people in won’t be enough. The cost of housing isn’t the big problem in Lower Price Hill, according to Hall of the Community Learning Center Institute. A typical apartment rents for around $700.

“If you look at the prices, you think, ‘OK that’s pretty affordable,’” she said. “What we’re having is an income issue.”

The median income is less than $15,000, and the unemployment rate is around 20%, based on the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data for 2017.

Another big part of Hall’s job is to help bring jobs back to Lower Price Hill. The neighborhood was once known for its heavy industry. That created a lot of pollution, but also steady employment for people in the community.

“Through disinvestment throughout the decades — the ’80s weren’t really kind to any urban area — it lost a lot of business,” she said. “So what we have also worked on simultaneously around housing is employment and bringing in businesses that make a commitment to hire residents.”

Nehemiah Manufacturing is a big win in that effort. The company opened a 180,000-square-foot facility last year on a notorious brownfield, where a toxic barrel-cleaning plant burned to the ground 15 years ago. Nehemiah has hired more than 70 people from the neighborhood so far.

Gabrielle Duncan, 20, is one of them. She slipped on a hair net and safety glasses one morning last month and stepped onto a factory floor, where workers were busy filling bottles of Downy Wrinkle Releaser and packaging Boogie Wipes. She took her post at a heat-sealing machine, pumping a foot pedal to close up trial packs of Pampers.

Duncan is a line captain at Nehemiah. It’s known as a second-chance employer, with a mission to hire people who often struggle to find jobs because of addiction, mental health issues or criminal records.

“I don’t have a record, but being down here, almost everybody you know has a record,” she said. “So I’m all for it, because I’ve personally seen people change. I know people can change.”

Duncan went to Oyler from ninth to 11th grade. She dropped out after getting pregnant.

“Right around the time that I was allowed to work after having my baby, Nehemiah opened up, so I ventured this way, because I live right up the street,” she said.

Instead of a traditional human resources department, Nehemiah has three social workers on staff who help with transportation, housing and child care. They’re helping Duncan find her first apartment. Company leaders say the extra cost pays off in lower turnover.

McAndrews Windows & Glass is another new employer. The company replaced the windows at Oyler School during its renovation.

“We could tell at that point in time how bad the neighborhood was, but you could see it starting to slowly improve,” said Troy McAndrews, the company’s president.

McAndrews relocated to Lower Price Hill back in March, drawn by the quick access to highways and downtown. Four of its 40 workers are locals, including Derek Hope.

“It’s convenient because I live across the street,” Hope said. “So that’s a win-win for me.”

One thing Lower Price Hill has going for it is its history. Much of the housing is ornate brick Italianate architecture from the late 1800s.

Steve Smith saw the charm when he started investing in the neighborhood in the 1990s. He’s CEO of the Model Group, an affordable housing developer. But he said he made a mistake when he developed his first project here.

“When we bought the buildings, they had apartments all the way down to the first floor along State Street, which is the commercial corridor,” he said. “All of those storefronts along State Street were bricked in, and we left them bricked in. We didn’t know.”

Now they know that it takes more than affordable housing to improve a neighborhood. The plan is to renovate his company’s Section 8 housing and add retail shops along that business corridor. A new nonprofit grocery store will open soon down the street.

“A neighborhood is like an ecosystem,” Smith said. “You need places for people to live, you also need places for people to work and play, you need a mix of incomes in a neighborhood.”

In the last decade, the Model Group has helped transform another nearby neighborhood, where houses like the ones in Lower Price Hill now sell for more than half a million dollars. To avoid displacing current residents, Smith said, the key is to preserve affordable housing before a neighborhood gets trendy.

“There’s so many vacant buildings, there’s room for everyone,” he said. “We can do addition without subtraction.”

Lower Price Hill is still a long way from trendy. A lot of the funding for all this development still has to be raised.

“We have the committed partners in the right places,” Hall said. “Some are farther along than others in having the dollars needed to get hammers swinging, but hopefully in the next two to three years, you’ll really see a transformation in the neighborhood.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.