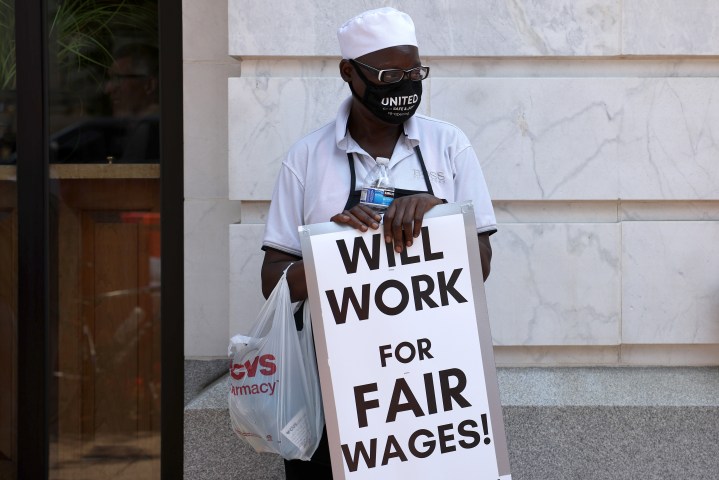

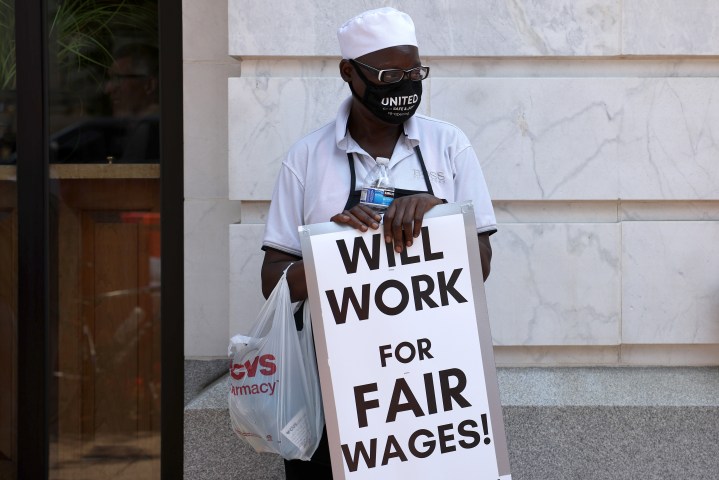

“The balance of power is shifting”: Ritholtz on the future of work and wages

“The balance of power is shifting”: Ritholtz on the future of work and wages

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee wraps up its June policy meeting Wednesday, and employment will likely be a big topic of discussion for Fed Chairman Jerome Powell. The conversation surrounding the more than 9 million job openings in this economy is the subject of a blog post by Barry Ritholtz, co-founder, chairman and chief investment officer of Ritholtz Wealth Management.

“Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal spoke with Ritholtz, also a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion, about why so many businesses are having trouble hiring and the future of work. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: We are asking, you say, the wrong question about so many jobs being available in this economy. Discuss.

Barry Ritholtz: Yeah, whenever I hear people say, “We can’t hire people,” they’re leaving out half of the question, which is “at these wages.” Hey, you know, ask anybody who’s tried to hire, and someone eventually says, “Maybe we need to up our wage offer.” And suddenly they’re flooded with [applications]. And we’ve seen that time and again in this economy.

Ryssdal: Take it beyond wage, though. There are some pandemic-specific things that you talked about in this post that are really germane to the future of employment and, and to some degree wages in this economy. Talk about that.

Ritholtz: Sure. So there’s two big factors that we’re looking at. One is clearly autonomy. And one of the things we learned from the work-from-home year validated for a lot of corporations who didn’t believe it that employees can manage their time, they can be productive. From the labor side, people have said, “You know what? I really like having control to set my schedule, to if I decide that today I’m not going to shave or shower, well, too bad. I’m going to work today in my pajamas.” And that level of autonomy is worth a substantial amount. I think that some of the hey, we’ve been too generous with unemployment benefits, you can find some examples of where that makes a difference on the periphery. But the flip side to that is the quits rate. That’s telling you this is much more than merely unemployment benefits. And that quits rate, it’s at all-time record highs. And that’s really quite telling.

Ryssdal: All right, so step back for a minute here. And I’m asking you this as a guy who runs his own company, you who is the definition of management and capital. You point out in this post, and Neil Irwin’s done it in The New York Times as well, that the dynamic between capital and labor, you think, is now just fundamentally changed.

Ritholtz: Yeah. Back in March, I noticed that the balance of power is shifting. And you know, the pendulum swings back and forth. But there is so much money around and corporate America has become so large and so profitable, that it just reached the point where labor is able to say, “Hey, you know, I’m not interested in this job. And apparently, neither are most of my peers. So if you want any of us to work for you, you better step up and pay wages.”

Ryssdal: All right. So look, $64,000 question. Do you think this lasts, or, as one imagines the economy reverts to the mean at some point in the next 18 months to two years, does this flip back and capital is in charge again?

Ritholtz: So what’s been fascinating about wages over time is that they tend to be sticky, which is why it’s that stairstep up instead of a smooth curve up. So wages go higher. And then, if we eventually succumb to the next recession, or I should say, when we eventually succumb, people tend not to see their wages cut. What you tend to see is layoffs. People look at wage increases as if they’re inflationary, but especially at the lower end of the salary scale, and certainly at minimum wage, it’s been lagging the overall economy by so much. It really is sort of a reset to catch up where wages might have been had we had that smooth curve, which hey, that’s unfortunately not how economics works.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.