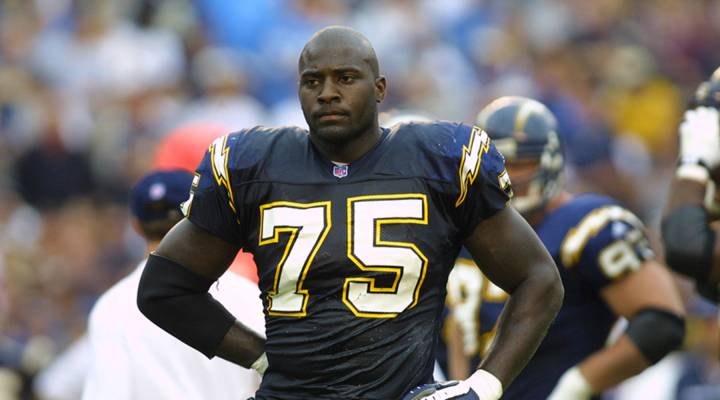

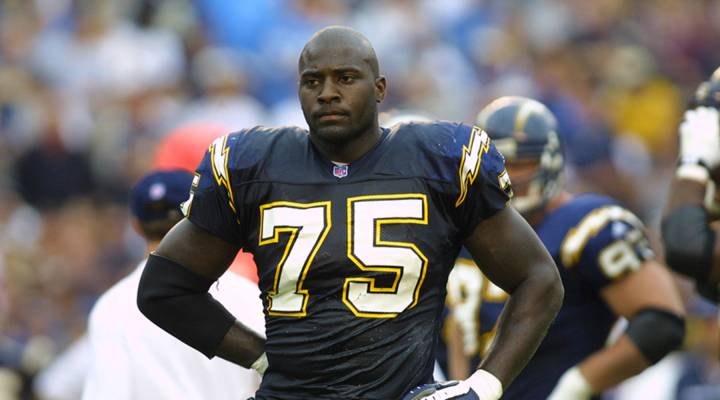

Former NFL player Marcellus Wiley on the economic realities of football careers

Former NFL player Marcellus Wiley on the economic realities of football careers

Making it into the National Football League can dramatically change a player’s economic circumstances, but the average NFL career lasts just 3.3 years, and life post-retirement can be challenging. Marcellus Wiley played 10 years on four teams in the league, made it to a Pro Bowl, then found his way to ESPN and now Fox Sports in his retirement. Given that Wiley went to Columbia University, a school that lacks a strong football program, the idea that he’d even make it to the pros seemed like a long shot. Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal talked with Wiley about his new book, “Never Shut Up: The Life, Opinions, and Unexpected Adventures of an NFL Outlier.”

Kai Ryssdal: So, about this book, first of all, it’s a great read, totally fascinating. I have to ask you about the subtitle though: “The Life, Opinions, and Unexpected Adventures of an NFL Outlier.” Since when are you an NFL outlier? Man, you played in that league for 10 years, you made a gazillion dollars.

Marcellus Wiley: Yeah. I guess that’s not so unique. But to get there was a unique experience coming from Columbia University, not the yellow brick road to the NFL.

Ryssdal: Let’s go back farther, let’s go back before Columbia, right? Because first of all, getting drafted out of Columbia, which has a terrible football team — apologies to all the fans —

Wiley: Way to speak the truth! (laughter)

Ryssdal: I know, right? You grew up like 3 miles down the road, in South Central L.A.

Wiley: I did. Born and raised in Compton. South Central L.A., right here in the heart of this city, in the heart of a lot of gang activity, the drugs, the poverty. I decided to be more responsible with my talents and only had two: academics and athletics.

Ryssdal: And size, right? I mean, you’re a physically gifted dude, too, right? That’s got to be thrown in there.

Wiley: Yeah.

The cover of Marcellus Wiley’s new book.

Ryssdal: Not my favorite story about you growing up down there, but maybe the most illustrative story, is the first concussion you ever had was not on a football field.

Wiley: No, it wasn’t. Crazy enough, when the concussion lawsuit came around for NFL players, they asked me, would I join it? And one of the reasons I didn’t join is because my first concussion was not football related. It was being on a park, 7 years old, on the swings, and all of a sudden, I see some gangsters coming up, acting like they’re my friends, “Oh we gonna push you little man, we gonna push you little homie.” So finally they pushed me off, and I flipped in the air, and in the air I think I’m just going to land in the sand and now take off running. Big boulder. I saw it coming. Ffwwp. Next thing I know, I’m in my grandmother’s house, a big hole in my head, nine stitches later. And that was another childhood experience, another day.

Ryssdal: So here you are now, I mean you’re somebody in the world of football and media and entertainment. The catch of course is, that for every one of you who plays 10 years, gets out reasonably healthily and has a career afterward, there are probably a dozen guys who don’t, who are done at 26 and can’t find their way through.

Wiley: Yeah, and that’s the sad part. With a degree, if they have it —

Ryssdal: If they have it, right —

Wiley: — from a school that is not going to be respected in the real world. And this is something that is a touchy subject for a lot of people, but I don’t understand it. These players get sold and told, and next thing you know, they’re in these football factories with a worthless degree to the real world. And then they’re three years in the league, they make $400,000 —

Ryssdal: Most of which they’ve blown.

Wiley: — they’ve blown. And then they’re in the real world, like, which way is up?

Ryssdal: So let’s go from one tricky issue to another one: the politicization of the NFL today with Colin Kaepernick and “take a knee” and those protests.

Wiley: Yeah. I wouldn’t have taken a knee if I were an active player, but I certainly would have been in full support of the cause. What would have occurred with me is what Colin Kaepernick started to do, which is, “OK, I’m going to give a million dollars of my own money for social injustice in my community. I want that matched by my owner.” And then I would have called a teammate or friend on every NFL team, 32 teams, ambassadors. “You’re the Colin Kaepernick of the New York Giants,” whoever that may be. Now we have $32 million, and I want that matched from the owners. I don’t think an owner with their business savvy would ever say, “You know, 80 percent of our league is African-American, and you know, these ambassadors have come up with a great economic plan for us to support. But you know, we don’t really want to support it. Get out of here.” The owners support every single cause that I’ve ever come upstairs with.

Ryssdal: Last thing, which gets to the concussion on the playground in Compton when you were a kid. Not the content in the playground part, but what football does to your body. You have a son who’s 3 now?

Wiley: Yeah he’s 3.

Ryssdal: You say in this book you don’t want him to play football.

Wiley: I don’t want him to play football at all. But I’m not going to tell him who he is and what he has to be. If he gets to the high school level and he’s like, “Dad, I want to play football for real, like NFL level, that’s my goal,” I’ma talk to him and let them know every level of pain, all of the emotional rigors and toll it takes on you, every experience. Let him know it’s a Wednesday, you’re a sophomore, and your friends are outside, and you’re sitting there bleeding from the elbow in class, and your fingernail is ripped off, and you’re sitting there trying to write. I mean, just let him know. I went through that process fueled by necessity. I needed the money, I needed the opportunity, but my son won’t. So what’s your drive? What’s your passion? Are you ready for those rigors? And if he answers yes, he has my blessing and support, but certainly, I’ll still have a basketball on the other hand.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.