Get your foot massages in China now, before the cheap labor runs out. That message brought to you by Wang Feng, demographer and one-child policy critic. Wang wants to raise the volume on this 30th anniversary of the policy. Born in China and now a professor at the University of California, Irvine, Wang blames the policy for a series of consequences that weren’t so unintended. And he notes the original document indicated the one-child policy would be temporary; time, he says, to phase it out.

Interview excerpts

Why is China so populous in the first place?

Mainly, a spectacular improvement in standards of living. And decline in mortality.

Between the early 1950s and early 70s, on average the Chinese person gained about 1.5 years in life expectancy. Per year. So we are talking about life expectancy increase from below 40 to close to 70 years old.

It’s not that the Chinese had more births. They always had about 5 children on average per couple. So it’s because of the mortality decline that drastically improved the survival chances of those children that China suddenly had a population explosion. What happened in China is not unlike other parts of the world at that time.

Why did Chinese leaders consider population control in the first place?

There was a shortage of consumer goods. Consumer durables were rationed in the 1970s: Matches, soap, eggs, sugar, cotton, cloth. Just think about it. Most of the stuff increasingly became more and more scarce.

It was mostly a problem of the economic system. Not a population issue. But the growing population did not make those problems go away. It made those problems more apparent. That also drove the determination of the leadership to accelerate and have a more forceful birth control program.

The early birth control programs were voluntary. Did they achieve their goals?

As early as the 50s, urban areas had voluntary birth control programs. The Chinese government actually supported abortion. Contraceptives were provided as early as in the 50s and 60s.

Then in the 1970s, the government began a not-very-coercive program. They advocated later marriage, longer birth intervals and fewer children, nationwide. And in one decade, China’s fertility level was more than halved. That was really the golden age of fertility decline, well before the one-child policy.

The one-child policy came soon after leader Mao Zedong died and Deng Xiaoping took power. Did the political climate influence the adoption of the policy?

Political legitimacy of the post Mao leadership was clearly at stake. If you look at the major achievement or the source of political legitimacy during the Mao period, it was national independence. Industrialization. So it was aggregate achievement. But what the planned economy failed to do was to deliver a decent increase in per capita standard of living.

So at the death of Mao, when China’s new leaders looked around its neighbors — and realized how far behind the standard of living in China was in comparison to Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea — they realized political legitimacy rested on how they could deliver a rapid increase in standard of living. And that has to be measured on a per capita basis. So in this calculation, population became the denominator for everything.

How did the policy become a policy? Hearings? Votes? I assume no presidential signing ceremony?

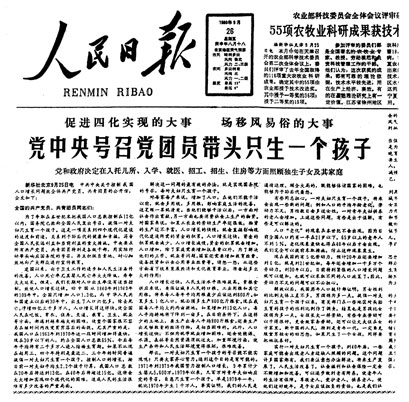

It came through almost through the backdoor. Not as a law, not an act, not even an announcement as a document, but as an open letter to the members of the Communist party and the Communist Youth League. To call for their support of the national economic growth agenda, and have only one child per couple.

It was not a formal document. But its real effect was no less than law.

Who wrote it?

It was a collective effort of scientists, social scientists and government officials. The letter reflected ambivalence. It admitted openly this would be a policy of only one generation. And it would involve the sacrifices of the Chinese population. And it would have a number of undesirable consequences, including rapid population aging, and effect on Chinese kinship and family structure.

They realized this was not a policy to last forever, but an emergency policy. There were no better choices. The original document anticipated the policy would be phased out in 20, 30 years — which is now.

The economy has changed, the demography has changed. However the policy has not changed.

Proponents of the one-child policy say it prevented 400 million births.

For sure it’s a bogus statement. Let’s look at a very simple comparison: Thailand, which has per capita income not too much higher than China now. Back in 1970, Thailand had a fertility level of five children per couple, about the same as China. And last year that number fell to 1.8.

About the same as China’s. So both countries fell at the same trajectory, one with a policy, one without?

About the same. So unless you say Chinese people are necessarily different from other populations, it’s very hard to argue all this fertility decline is due to the government policy.

We cannot rewrite history. But based on everyone else, and what we know about the reproductive desires of Chinese couples now, fertility would have declined for sure in China.

Lots of young couples tell me they don’t even want two children. Why not?

The surveys we have done find a sense is economic uncertainty: the cost of education, cram schools the fees to get into elite schools, and then getting children into good universities and buying them apartments in the city.

This could be uniquely Chinese. For some reason all Chinese parents want kids to do better than themselves. It’s very deeply ingrained in the society, in the culture that the parents want their children to be successful and live a good life and be better than themselves.

It’s awfully different from the North American model: “Good luck in college, son. Don’t come back.”

The bond between parents and children is never ending in China, until one ceases to exist. Chinese parents pay for education well beyond 18. They’re also responsible for buying the apartment or building a house in the countryside for the son to get married. And then take care of the grandchildren.

You’ve warned China will have fewer young people down the road. Implications?

China has entered a demographic watershed, because of the deep fertility decline. China is now seeing declining numbers of elementary school students, of college entrance exam takers. And of young new entrants into the labor force.

Between 2010 and 2020, the annual size of the labor force aged 20-24 will be shrunk by 50 percent. A drastic decline. And this trend will continue. So the time of abundant, cheap Chinese labor is over.

Economists debate this. in your view, has the labor shortage started yet?

It has already started. A couple years ago labor shortage was reported in certain locales. And now the decline in young labor has already started.

You’re telling me this country of 1.3 billion people is running out of workers?

It’s relative to the Chinese population and relative to the Chinese economy. When you look at the of the Chinese labor force or the total number of young laborers it’s sizable.

But remember the economy is also very large. So we are looking at the ratio of the young labor force to the whole labor force. And that is going to decline very rapidly.

You are not going to see so many beauty parlors and places where you get foot massage, because they have trouble finding workers.

OK, whoa. This is serious.

They are already having problems getting young laborers from the rural areas.

It’s not just the shrinking in the size of the young labor force. But also the pulling effect from the changed Chinese families. When most families have only one child, that only child might not want to move away, to be a migrant laborer. They might want to stay nearby. And as time goes by, aging Chinese parents would need their support. Not just money, but daily assistance and emotional contact.

So the continued large migration flow is also going to slow down.

What’s the profile of the one-child generation? We all call them “Little Emperors.”

It’s a very unfortunate generation. I think they are very stressed because their parents basically they put all their eggs into one basket. That’s their only child and they want their child to succeed.

It’s not just that they get all the resources, are spoiled, but also their parents expect them to succeed. It’s not easy to be a single child.

And what’s waiting ahead for them when their parents grow older will be extremely challenging.

Help me understand the aging thing. Is China gonna morph from a young, vibrant place like Silicon Valley, to an aging locale, like say Arizona or Florida?

At the aggregate level, there are fewer and fewer taxpayers in relation to the pension collectors. At the individual level you will have really these only children taking care of their parents and their grandparents.

Many families still prefer baby boys over girls, and can use sex-selective abortion. This makes for a huge surplus of men down the road, yes?

Since the start of the one-child policy in 1980, China has had an abnormal sex ratio, in the range of 120 boys to 100 girls.

So you have these excess males — or shortage of girls — due largely to sex selective abortion. That is a demographic force that will be going against men in terms of finding marriage partners. That will make the marriage market in terms of balance between men and women increasingly competitive.

We are already seeing this. The last couple census have shown for educated, urban men by age 40 almost all are married. Like less than 1 percent still single. But if you look at remote rural areas among men with less education, one in 4 are still single at age 40. So the marriage market will get more intensive and competitive. And men of lower social ranks, less economic resources are going to be left out.

Will we then see more human trafficking, bride buying from lower-income places?

Clearly, people will go to the next periphery. But to buy a bride you need resources. The poorer men in remote villages, they don’t have the information, the resources to do that. So there will be many men who will not have wives.

You’ve laid out these problems associated with the one-child policy to Chinese leaders. Have you convinced them to relax it, or phase it out?

So far the leaders have been dragging their feet. For every year of dragging feet, China adds 5 million more single children, and 5 million more families with just one child. These families are the foundation of Chinese society.

Politicians are all nearsighted. Not many would do something for the long run to sacrifice for the short run. It’s understandable. I think it’s the nature of demography.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.