Why baseball stadiums are all a little bit different

Why baseball stadiums are all a little bit different

Next time you’re watching a major league baseball game, take a second to notice the where it’s being played. Is the stadium in the suburbs or the city? What kind of materials is it made from? Is it enclosed or fully open to the sky?

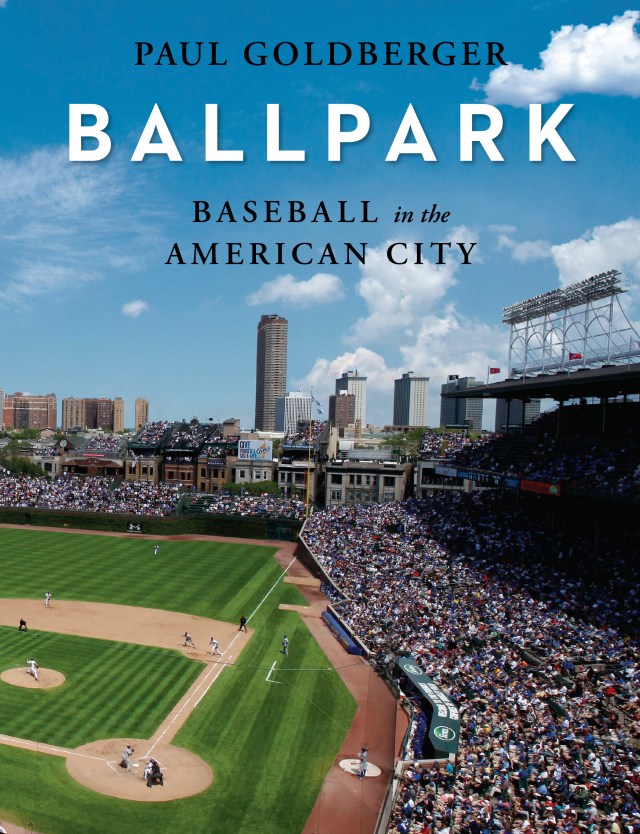

In his new book, “Ballpark: Baseball in the American City,” architecture critic Paul Goldberger makes the case that the history of ballpark design is a manifestation of our changing relationship with cities. He talked with Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal about some of the forces that have shaped ballpark design. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: We should say, first of all, this is not, as you point out in the book, it’s not an encyclopedia of all the ballparks in America and the world.

Paul Goldberger: Definitely not, no. It’s not a guidebook, it’s something different altogether.

Ryssdal: Well, OK. I was gonna tell you what I think it is but you tell me … you tell me what you think this book is.

Goldberger: Well it’s a book about baseball parks as American public space really, and how the history of ballparks and the history of American cities are kind of deeply intertwined.

Ryssdal: And the root of that intertwined-ness, if I can coin a phrase, is the part of the word in the title of this book “park.” It’s a little park, it’s a little garden space, it’s a little greenery in the middle of what are often really dense urban environments.

Goldberger: Absolutely. It’s why baseball parks are very different from any other kind of athletic facility, really. Baseball is technically played in both infinite time and infinite space. You know, only the diamond is exactly prescribed; the outfield, it is what it is. And in fact, the eccentricity and idiosyncrasy of ballparks was part of the nature of baseball, as it grew up.

Ryssdal: Take us to the point where cities and ballparks sort of came to be one.

Goldberger: Well, it really goes back to the beginning of baseball, which, despite the myth of Cooperstown and Field of Dreams, is as much an urban sport as a rural one. And people started playing baseball on the edges of cities, in open space, and then more and more people were interested and they started charging people to come in and watch people play baseball, and thus the baseball park was born.

Ryssdal: Not to jump too far ahead in history, but there’s Fenway, there’s Tiger Stadium, there’s also Wrigley Field.

Goldberger: Yes, there is. It’s on the cover of the book.

Ryssdal: It is. I know it’s on the cover the book, but I want to pull up a quote by Mr. Wrigley himself who said: “Baseball is too much of a sport to be a business, and too much of a business to be a sport.” Somehow, these men — and they were all men — found a way to make it work to the tune of, today, billions and billions of dollars.

Goldberger: Yes, absolutely. Wrigley, though, had a really interesting take on it which is that he did not invest very much in his team itself, which was maybe not so smart. It took a long time before the Cubs were doing very well. His whole idea was that if you give the people a pleasant place to go out on an afternoon, they’ll come, and they care more about that than about whether the team wins or loses. I don’t think that was really true. But the “give the people a pleasant place to come” part certainly was true and right. And I think it’s one of the reasons Wrigley Field is so beloved.

Ryssdal: This is a little bit sideways, but Wrigley Field, Yankee Stadium, Dodger Stadium, here in town, even though it’s certainly the younger by decades of the fields I mentioned so far … they have become points of civic pride to this day.

Goldberger: Absolutely, yes. Which is why, happily, they still have their names and they don’t have names that are for sale to the latest corporate bidder. You know, whatever one can say about the Yankees, at least they didn’t sell the name of the place.

Ryssdal: I should tell you, full disclosure here, I grew up a Yankees fan. Although, not for nothing, the new Yankee Stadium — if I could just take you on a completely personal detour here — for my money, it has no soul. It has no soul.

Goldberger: I don’t love it, either. Although I think, in the end, it’s a pleasanter place to go to a game than Yankee Stadium had been, because the old Yankee Stadium was really gone. It was destroyed in a terrible renovation in the ’70s.

Ryssdal: Yeah I remember that one as kid.

Goldberger: If it had been kept, I would have had a very different opinion about whether the new Yankee Stadium should have been built at all. But since it was really gone anyway, and turned into one of the worst concrete relics of the ’70s, I figured we might as well start over.

Ryssdal: All right, so I’m mixing my decades here. But talk to me, then, about Camden Yards. So, we went from the Wrigleys, and the Fenways, and it was all great. And then we went to the ’50s and ’60s, where you had the enclosed stadiums and the concrete and all this, right? And then, in 1992, along comes Camden Yards, which was a revelation.

Goldberger: Total revelation. Baseball is the only thing that’s changed 180 degrees because of one place, and that was Camden Yards in Baltimore where the management of the Orioles in the late ’80s said they wanted something that had the feeling of an old-time ballpark. The formula has been replicated in a couple of cases. I think even improved on, and built on I think Pittsburgh is fantastic, actually, and even better, PNC Park. San Francisco, I think is really wonderful, what’s now called Oracle. There’ve actually been quite a few that have taken the Camden Yards model and gotten even farther with it, and done things even better and very unique to their cities.

Ryssdal: So next time I’m in Dodger Stadium, which is a mile from here — which I love, by the way, I mean, there’s nothing like, you know, 7:10pm start at Dodger Stadium.

Goldberger: Dodger Stadium is one of the greatest places there is to go to a ballgame. It’s maybe the worst place to get into and go out of, but once you’re in your seat, it is, I think, pure, absolute pleasure.

Ryssdal: So, what should I, as Joe Baseball Fan and mildly interested in architecture, what should I be looking for?

Goldberger: Well, you look for that really wonderful kind of nice geometric, 1960s vibe that has, actually, almost a little bit of a kind of Disney Tomorrowland vibe to it. And in fact, they were influenced by Disneyland, which was only five years old when this was going up.

Ryssdal: Oh yeah, makes total sense.

Goldberger: A baseball park really should feel like it’s in that place, and that place alone. When you’re in Pittsburgh, you see the bridges and the skyline. When you’re here, at Dodger Stadium, you see the mountains toward Pasadena. I love that. That’s one of the things that makes being in a ballpark so special.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.