Schools spend billions on security measures. But which ones are effective?

Schools spend billions on security measures. But which ones are effective?

Michelle James is considering sending her daughter to Archbishop Wood High School in Bucks County, Pennsylvania next year. So on a recent morning, they went for a visit.

James was thinking about her daughter’s safety.

“It makes me emotional,” James said. “So I don’t like talking about it. But active shooters, things like that — you’ve got to worry about that stuff nowadays. I’m dropping my child off, I want to make sure she comes back home.”

Last week’s shooting at Saugus High School in southern California was the 70th school shooting in the United States this year, according to data from the Center for Homeland Defense and Security at the Naval Postgraduate School. Schools are spending increasing amounts on safety and security: by 2021, some $2.8 billion annually, according to research firm IHS Markit.

But there isn’t much evidence about whether the security measures they’re putting in place are effective.

Archbishop Wood High School’s leadership knows that safety is important to parents. There’s a staff member posted at the main entrance of the school who checks in visitors. Students swipe into the building with their ID cards. Once they’re on school grounds, the kids are watched by 32 cameras.

“They’re all over the place,” said Gary Zimmaro, president of Archbishop Wood. “They’re in the gyms. They’re in the cafeteria. You walk down the hallway, we can see you. You walk outside, we can see you.”

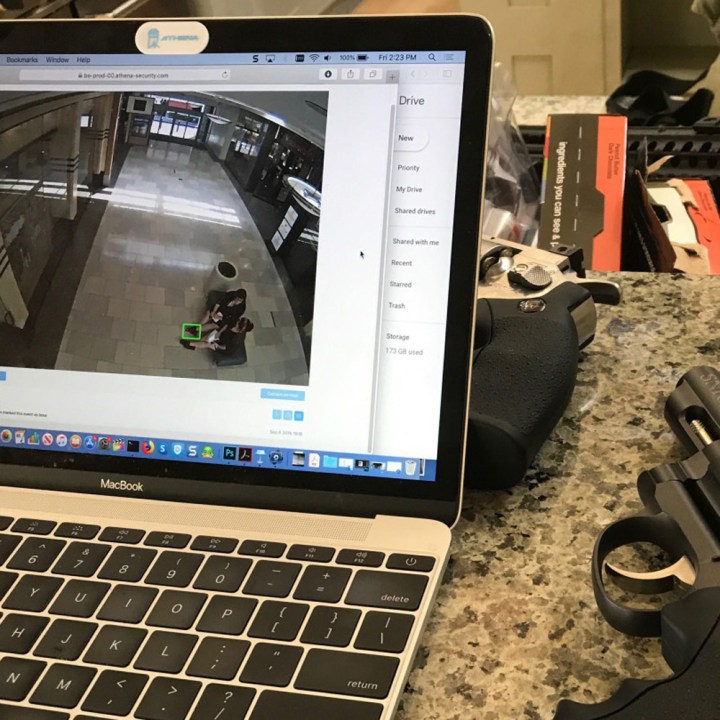

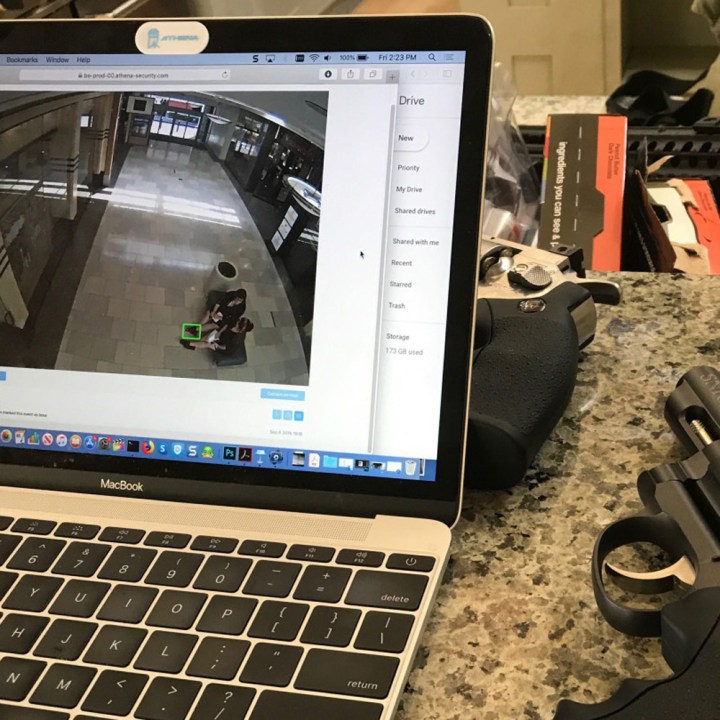

A company called Athena Security can also see you — and what you might be carrying. The startup uses artificial intelligence software to monitor the school’s cameras and detect if someone’s holding a weapon.

Archbishop Wood has to compete for students with local public schools. So it wants to give parents all the reasons it can to spend $9,400 a year to send their kids there. Zimmaro said high-tech security can give the school a competitive edge.

“We are surrounded here with very good public school districts,” Zimmaro said. “Part of our job is to make sure that we’re competitive and compliant with the same thing that they’re doing.”

“And actually, they don’t have Athena,” he said. “We do.”

Archbishop Wood was Athena’s first client. One of the school’s retired teachers is the mother of Athena’s CTO, Chris Ciabarra. (Ciabarra also gave the school an $85,000 gift for a career counseling center.)

Now, the startup has about 50 clients. It sees any place with security cameras as a potential customer — malls and churches as well as schools. The company charges an initial fee of $400 per camera, followed by a regular monthly fee of $100 per camera.

The company doesn’t make the cameras itself — just the artificial intelligence software that monitors existing networks. In order to put the “I” in its AI, Athena needs to train the software by showing it lots of footage of people holding weapons.

But there isn’t much footage like that in the public domain, and almost none is from the perspective of security cameras 10 to 12 feet in the air. So, Athena has been creating its own footage.

Ciabarra provided the set — his home in Austin, Texas — and acted as director.

“You’re gonna come in from outside with a gun,” he told an actor. “The camera’s gonna be filming you here.”

The actor (hired from Craigslist) charged into the room waving a realistic fake gun around.

“Get down on the ground!” he yelled. The rest of the group ran in different directions.

Ciabarra yelled “Cut!” and gave the actors instructions for another take, this time with the gunman wearing a hat. The idea is to give the AI as many variations as possible so it can pick out the gun no matter what the person holding it looks like.

Athena’s software still makes mistakes. On average, every camera misidentifies an ordinary object as a weapon twice a day. It might see someone holding a cell phone at an odd angle and flag it as a gun. So humans look at every image the software identifies as a weapon.

There’s not a lot of information on how to effectively prevent school shootings. The U.S. doesn’t collect data on existing security measures at the more than 100,000 schools nationwide.

But schools still feel pressure to do something, according to Tim Servoss, who studies school security as a professor of psychology at Canisius College.

“That might involve getting some super high-tech facial-recognition software, so you can identify potential threats,” Servoss said. “That might involve purchasing bulletproof smart boards for your classrooms. But there isn’t any evidence those things are effective.”

Congress has appropriated $1 billion over ten years for school safety equipment, as well as training to prevent violence. But in order to cover the cost, the appropriation eliminated funding for research to determine what’s actually effective.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.