Braille versions of textbooks help blind college students succeed

Braille versions of textbooks help blind college students succeed

When it came time for college, Kayla Weathers said she thought she was prepared.

She attended public school for all of her educational career up to that point, except for her last two years of high school, when she attended the Georgia Academy for the Blind in Macon. Weathers is blind and uses a white cane to get around. But still, she said her first semester at Dalton State College in North Georgia was difficult.

“I didn’t do terribly, like I didn’t flunk out or anything, but I was, like, I need to, you know, have more confidence,” Weathers said. And although it wasn’t the only reason she struggled to adjust, it didn’t help that she had trouble with the course materials.

For blind students, some classes can feel out of reach because textbooks and exams may not be readily available for those courses in a braille format.

But now a major braille publisher in Atlanta is working to make higher-level classes more accessible to college students.

The AMAC Accessibility Solutions and Research Center at Georgia Tech was founded in 2006. Its braille production center is one of the only places in the U.S. that caters to blind and visually impaired college students.

Weathers said in addition to gaining more independent living skills, she had to learn how to advocate for herself, such as requesting accommodations from professors. As part of her adjustment, Weathers learned to explain to professors, at least a semester in advance, that she would need class materials to be transcribed to braille or provided in an electronic format that she could listen to. During exams, a professional scribe sat next to Weathers so that she could dictate her answers to the scribe, so that the professor could understand them.

“It’s kind of funny. I tell people I’m a visual learner even though I’ve been totally blind my entire life, but to really understand something, especially academically, I would prefer to read it and have it under my fingers because I feel like it sticks in my head better,” Weathers said.

Weathers went on to make history in December 2016 as the first fully blind student to graduate from Dalton State.

The University System of Georgia, which consists of 28 public colleges and universities, has an average of 350 students each year who are blind or visually impaired.

Since universities are not required to collect information about students with disabilities and the type of disabilities they have, it is hard to quantify how many students may need vision-related services.

But the American Foundation for the Blind estimates there are about 245,000 college students nationwide who are blind or visually impaired nationwide.

Many schools send requests for braille transcription to the AMAC Accessibility Solutions and Research Center at Georgia Tech, which has a printing press. Guy Toles, AMAC’s braille services manager, said his department processes about 400 orders per year, including requests for science, technology, engineering and math courses.

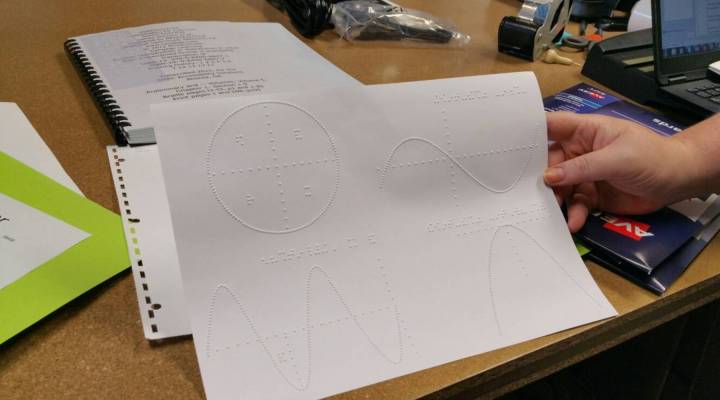

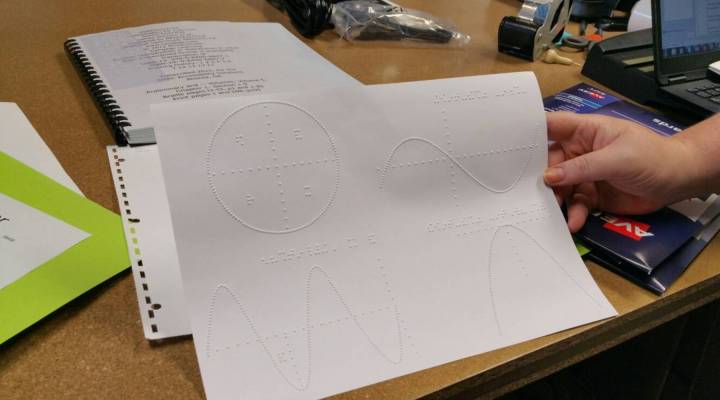

“Those subjects require advanced codes, the need to see things in a spatial arrangement, but then also, the maps, charts, diagrams and figures that have to be recreated in order for the braille reader to feel and understand a concept,” Toles said.

There are eight people at AMAC dedicated to braille transcription services. But most of the transcription work is produced by an unlikely group of outside contractors: prisoners and ex-convicts.

Becky Snider is public relations manager of the American Printing House for the Blind’s National Prison Braille Network in Louisville, Kentucky. Her group helps teach inmates how to read and transcribe braille materials. She said prisoners tell her they enjoy the human connection of the work they do, and it offers them a practical skill.

“There’s a child out there in a classroom who now is able to participate fully in a classroom because of something that [they’re] doing,” Snider said. “I think it raises self-esteem and gives people a sense of purpose.”

The prison braille program has doubled over the last decade, expanding to more than 30 states.

Braille books are more expensive than most college textbooks. Converting just five chapters of a science book, the average order, into braille can cost up to $15,000. But once it’s on hand, braille reprints cost about 5 percent of the original cost, or about $500.

Since braille takes up more physical space, Toles said a math book that is 1,000 pages could easily be “5,000 braille pages.”

Toles shows off a biochemistry textbook, which includes diagrams of molecules that mimic a collage art project. Strings of yarn and strips of paper are embedded amidst the braille.

“The types of subjects that I see students who are blind and vision impaired are enrolled in now from an aeronautical school, to some of the highest levels of math, computer coding. I think that’s a sign that equal access is only going to improve,” Toles said.

And that’s what Weathers is working on now. She’s applying to graduate school. She said one day, she wants to teach other blind students how to navigate college.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.