Human biases are baked into algorithms. Now what?

Warning: A tweet below contains an expletive.

Algorithms, the computer programs that decide so many things about our lives these days, work with the human data we feed them. That data, of course, can be biased based on race, gender and other factors.

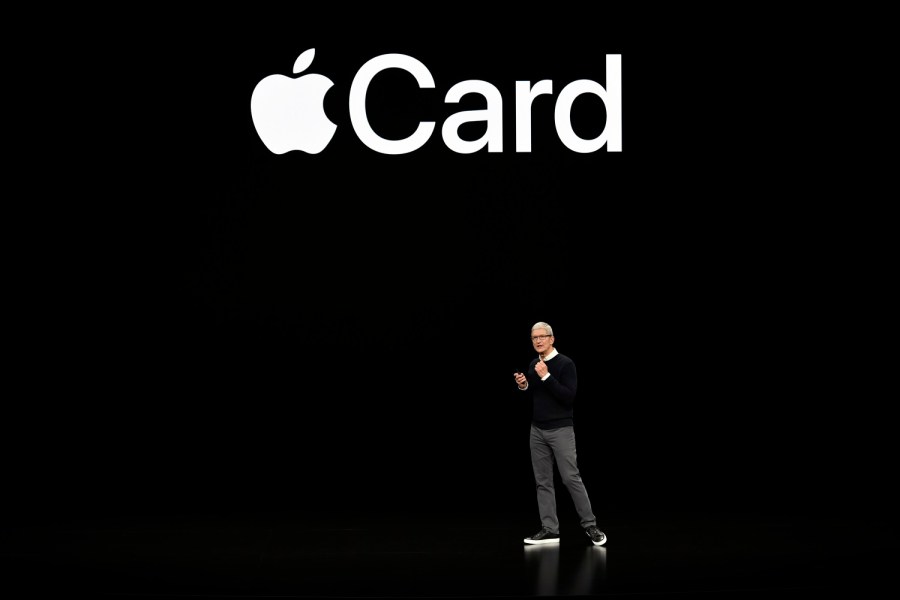

Recently, regulators began investigating the new Apple Card and Apple’s partner, Goldman Sachs, after several users reported that in married households, men were given higher credit limits than women — even if the women had higher credit scores.

I spoke with Safiya Noble, an associate professor at UCLA who wrote a book about biased algorithms. She said women having little financial independence or freedom over centuries is reflected in the data algorithms use to evaluate credit. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Safiya Noble: You’d look at that history happening by the hundreds of thousands of transactions a month or more. That starts to become the so-called truth or the baseline of data that gets collected into these systems. This is one of the reasons why women still have a very difficult time, and I think the Apple credit card was a perfect example of the flawed logics. The unfortunate part is this happens a lot to working-class people, people who aren’t rich and who may or may not even know what’s happening to them.

Molly Wood: When you look at bias in algorithms, is it bias that is introduced by the builders or by the data?

Noble: It’s both, because there’s an assumption by the builders that the baseline data that they’re using to train their algorithms is reliable or that it’s just the truth — that’s what happened. And yes, that is what happened, but it happened because of discriminatory public policy. It’s also about the interoperable data that’s moving from one system to another system behind the scenes, the way that financial services, companies and insurance companies are trading, buying, selling data about us and making profiles about us that, quite frankly, probably are not very reliable.

Wood: It sounds like you’re saying that this is a problem that is compounded in a whole bunch of different ways. I might be a programmer working on an algorithm, but I’m working with a flawed dataset that has maybe been passed through multiple companies and contains many errors that the consumer will never be able to correct because they’ll never see them. It feels a little intractable as a problem.

Noble: I think it is intractable, and I think we are entering a new era of need for consumer protection from these scenarios that are happening again every day all over the world, quite frankly. It’s very difficult to figure out how you’re going to reconcile. We know that people have a hard time just correcting things on a credit report. Well, times that by potentially dozens of companies that are making data profiles about us, that are determining whether we have access to a mortgage, to credit, small business loans. We might even see in the future college admissions, high school admissions, all kinds of predictive analytics being used in determining whether we will have an opportunity or not. I think this is something we’ve got to pay attention to right now.

Wood: Is it possible to construct algorithms that don’t perpetuate bias? Is this even a problem that technology can solve?

Noble: This is not a problem that can be solved by technology, because there is no perfect state of mathematics that’s going to solve these social inequalities. The way that algorithms get better is when society gets better, when we don’t discriminate, when we have ways for people to be restored after they’ve been discriminated against. When you compound that by decades or even centuries of discrimination, you’ve got to address those fundamental baseline issues. The technology is not going to be able to mitigate that long legacy of data and information that’s feeding it. These are the things that I think when we hear people say, “We’re trying to make an unbiased algorithm,” we might want to raise an eyebrow and say, “How is that even possible?”

Wood: Because you’d have to invent in some ways a history or equalize data that can never be equal?

Noble: You would certainly have to mitigate or account for the legacies of discrimination and then figure out how you’re going to resolve making some type of predictive analytic or algorithm that reconciles that. Maybe there’s a restorative field of algorithmic design that might emerge where we can truly mitigate inequality on a mass scale. It doesn’t happen just at the level of math; it happens in the real world with access to affordable housing, access to good jobs, health care, education. You have to think about all the systems in our society and simultaneously address those things, too.

Wood: What are the stakes? How pervasive is this technology already in ways that we aren’t necessarily aware of?

Noble: The technology, I think, for people in the United States and throughout Europe, certainly parts of South America and the continent of Africa, is increasingly ubiquitous. If you are using the internet, if you are using internet-connected devices — smartphones, computers, all kinds of electronics — you are in this internet of things that is trying to figure out who you are and aggregate you into groups that can be sold to advertisers. There’s a constant 24-by-7 level of extraction that’s happening from the public in order to capitalize upon our emotions, upon our sentiments, our curiosities. I think that we might find ourselves in a place down the line where there’s a well-curated life experience that happens through all the data that’s been collected about us and our families. We certainly see things like banking and financial services using our social networks to determine our creditworthiness. That means a lot for people who are, let’s say, first-generation college students, people trying to aspire to the middle class whose whole community — whole neighborhood, whole family — has been working poor, and algorithms deciding that you’re going to stay in that state. I think we’re going to see more and more of these systems intruding upon the quality of our lives. We need to just take a moment, and we need to really think about why this is OK. We certainly wouldn’t let other industries, like pharmaceutical industry, for example, experiment with drugs and roll it out in CVS and Walgreens on the weekend and say, “Let’s see what happens.” We need that oversight on these technologies. They shouldn’t really just be made and rolled out on the public and then we find out the consequences later.

Wood: We are moving at full speed, it seems like, toward an algorithmically determined society. What do you think some of the solutions might look like, or the protections?

Noble: I think we’re going to have to reconcile that we need public policy, we need anti-discrimination laws that are specific to the tech sector and the way that tech is predicting decisions or foreclosing opportunities or opening up opportunities. We need to be able to see into those processes, but it’s not enough just to make the code transparent. I’m not sure that it’s particularly valuable for an everyday consumer to see 10 pages of computer code, and now that they can see that say, “Oh, now I understand what’s happening. It’s completely transparent.” That’s not the solution, just the total transparency. I think people need to understand what does it mean that the GPS tracker that’s on your phone is combined with the data that comes through your Fitbit, and your biometrics is communicating with your insurance company and might be available to your employer. All of the ways that this data gets commingled and developed. You wake up and you’re not really sure what’s been handed to you, what’s been afforded to you, what opportunities can come your way, because you really don’t know the decision-making processes that are involved in all of this predictive analytic work. That’s something that I think we’re just in the beginning stages of thinking about regulating. Quite frankly, it’s difficult, because our policymakers aren’t even entirely sure how these systems work. I’m not even convinced, in fact, that all of the tech companies as they’re interacting with this data, know entirely what will happen. It feels like a bit of a mass experimentation on the public.

Related links: More insight from Molly Wood

Goldman’s CEO went on to say that the bank would, over time, deliver more transparency to users about how credit is decided. Another big complaint about algorithms these days is that they help spread and amplify misinformation and divisive content.

Several Democratic presidential candidates have talked about ways to regulate Big Tech, including breaking up giants like Facebook, Google or Apple. One of those candidates, tech entrepreneur Andrew Yang, put out a tech policy proposal recently that calls for a new department in the U.S. government that would regulate social media and other algorithms. It would require that sharing and political ad algorithms be either open source or shared with something he calls the Department of the Attention Economy.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.