A look at the economics of early voting and caucus states

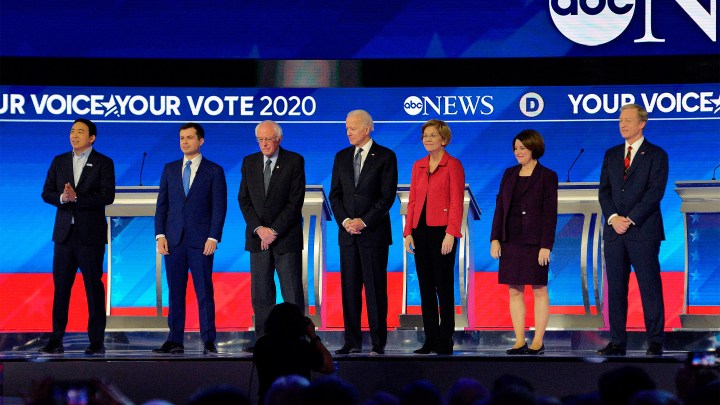

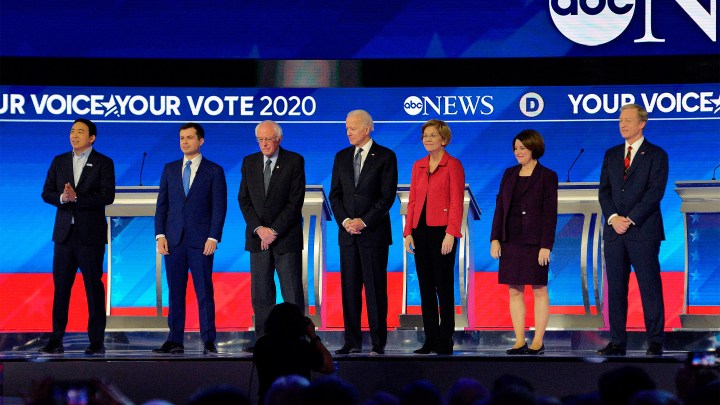

The 2020 election is shaping up to be a bitter partisan battle, and it will be waged in part over how people feel about local economic conditions and their own personal finances.

Some basic facts aren’t in dispute: unemployment is near a 50-year low, at 3.6% (January 2020), according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Job growth has continued every month for the past decade at a rate well above what’s needed to absorb new entrants into the workforce; it averaged 211,000 per month from November 2019-January 2020.

Beyond that, each of the early primary and caucus states — Iowa (Feb. 3), New Hampshire (Feb. 11), Nevada (Feb. 22) and South Carolina (Feb. 29) — has specific economic dynamics that shape voters’ concerns, and candidates’ pitches for votes.

As of December 2019, unemployment was significantly below the national average in Iowa (2.7%), New Hampshire (2.6%), and South Carolina (2.3%). Nevada’s unemployment rate was close to the national average (3.8%).

But the states diverge significantly on job growth. The U.S. added 2.1 million jobs in 2019 — a 1.4% increase year-over-year. But, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Iowa lost jobs on net (down 0.2%), while New Hampshire had virtually no net job growth, (up 0.9%, which is not statistically significant according to BLS). South Carolina grew employment by 1.3%, close to the national average, while job creation in Nevada surged ahead at 1.9%.

Iowa and New Hampshire have less dynamic economies, with aging labor forces, and population stagnating or declining in many rural and small-town areas. Iowa’s big cities are attracting more business and population, while New Hampshire’s southeast corner benefits from the growth and dynamism of the Boston metro area nearby.

South Carolina, meanwhile, has grown a number of industries in the past few decades, with new housing boosting urban and suburban areas; tourism and resorts growing in places like Hilton Head on the Atlantic Coast; and large manufacturing operations locating in Spartanburg (BMW) and the Charleston area (Boeing). Even with the recent slump in manufacturing tied to the U.S.-China trade war, South Carolina added jobs in construction, logging, leisure and hospitality last year.

Nevada’s economy was hit hard during and after the Great Recession by the foreclosure crisis and crashing property values. But the state has rebounded in the decade since, led by strong growth in tourism and casinos, and continued in-migration of retirees and immigrants. In the past year job growth has continued to be strong in leisure and hospitality, construction and e-commerce.

The Democratic candidates making their economic pitches will likely keep issues of income and income inequality front and center. Nationwide, wage gains have slowed in the past year (average hourly earnings rose 3.0% year-over-year in December 2019).

Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina follow the federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour. That’s left workers in low-paid jobs in retail, health care, leisure and hospitality, maintenance, logistics, construction and manufacturing at or near the bottom of the income scale nationwide.

Last year, House Democrats passed legislation to increase the federal minimum wage to $15/hour by 2025 (it hasn’t increased since 2009). The bill is opposed by Senate Republicans and the White House.

As a result, minimum wage hikes at the state and local level have been the primary driver of income gains for low wage workers in recent years.

Nevada’s minimum wage — currently $8.25/hour — will rise to $9/hour in July 2020, and will reach $12/hour by 2024.

Unions representing hotel and restaurant workers, health care and government employees in Nevada, including the Service Employees International Union and the Culinary Workers Union, have pushed for the higher state minimum wage. Those unions represent a large number of black and Latinx workers. The unions have also won significant wage and benefit improvements for their members in recent contracts — a fact they will no doubt tout on campaign stages with progressive Democratic candidates leading up to the Nevada caucuses later this month.

Correction (Feb. 11, 2020): The voting date for South Carolina was misstated, the text has been updated.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.