How government-mandated “guardianship” enabled the Osage murders

Share Now on:

How government-mandated “guardianship” enabled the Osage murders

We’re reading and watching “Killers of the Flower Moon” for Econ Extra Credit this month. The 2017 true crime book, and its new feature film adaptation, shine a light on the conspiracy to murder Osage people for their oil rights in early 1920s Oklahoma.

Before anyone was linking the title “Killers of the Flower Moon” with Leonardo DiCaprio or Robert De Niro, I had read David Grann’s nonfiction book and was shocked and fascinated. As a business reporter who has covered the fraught modern legal arrangement known as guardianship, I was angered to read about how guardianship was used to rob and exploit members of the Osage Nation at industrial scale. Before seeing the film, I had wondered if any of these corrupt guardians would make it into Martin Scorsese’s rendering of the history. Yes, they assuredly did.

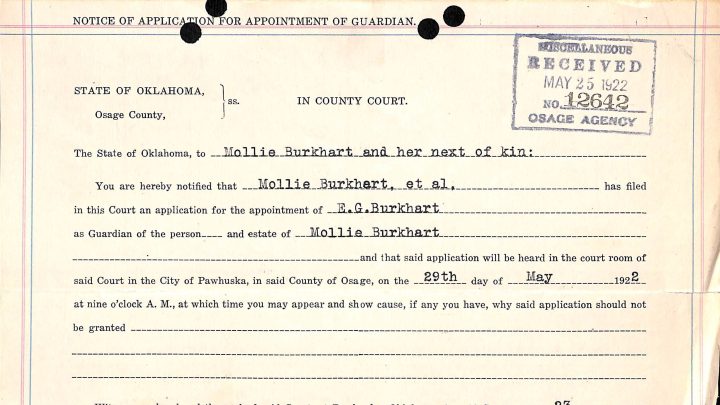

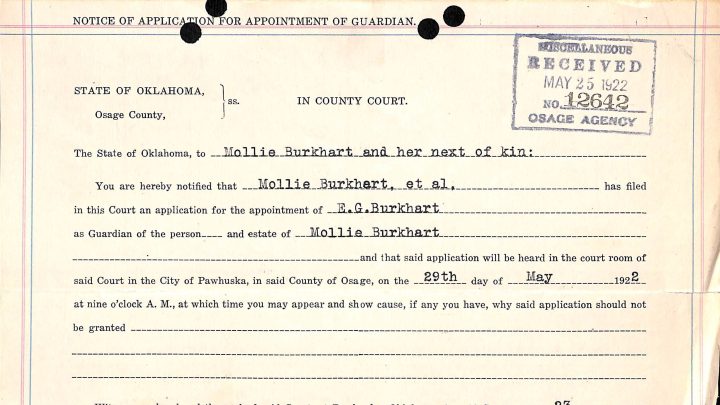

After Osage people were driven from their land into parts of Oklahoma that were poor for farming, a treasure of crude oil was discovered. The Osage people negotiated mineral rights, and some tribal members became among the richest people on earth for a time. But under federal law, many Osages were not free to do as they wished with the wealth. Under a particular system of guardianship imposed by the government, Osage people without some white ancestry were deemed “incompetent” and assigned a non-Native lawyer, businessman, politician or rancher as a kind of financial manager. The guardians were empowered to say yes or no to purchases as small as a tube of toothpaste. It was paternalism at a grotesque level. In the book, Grann refers to a guardian who viewed an Osage adult as “a child six or eight years old, and when he sees a new toy he wants to buy, he buys it.” Congress passed a law in 1921 reaffirming that Osages without any white ancestry would remain legally “incompetent.”

Guardianship without oversight was an invitation to widespread corruption. Guardians used their power to create, Grann writes, “an elaborate criminal operation, in which various sectors of society were complicit.” A terrible irony in all of this is that the federal government’s legal duty to protect Native Americans, underpinning the guardianship arrangement, did not extend to protecting Osage people from the conspiracy to kill tribal members for their oil rights.

I spoke to Jean Dennison, a citizen of the Osage Nation and a professor and co-director of the Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the University of Washington about this form of structural racism.

“You have this moment in time where you have corrupt people taking advantage of the fact that the federal government has created a void of justice in the Osage Nation where the governance systems that existed for the Osage had been stripped away from us,” Dennison said. At a time when the government should have helped the Osage Nation rebuild its own justice systems and help to punish criminals from outside the tribe, Dennison said Washington concluded instead that the Osage people “can’t handle their own affairs themselves.”

In “Failed Protectors: The Indian Trust and ‘Killers of the Flower Moon,’” a law review article, Matthew L.M. Fletcher of Michigan State University College of Law explores how the federal government doctrine to protect the “Osage Nation and its citizens should have forced the United States to act quickly, at least when non-Indigenous people began to swindle and murder Osage people. But under the government’s theory of the duty of protection, there was no obligation at all.”

It took an awful long time for the federal government to get serious about investigating the Osage murders. J. Edgar Hoover pushed for an aggressive federal investigation in part to try to make a name for his fledgling Bureau of Investigation, later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. But the BOI took action only after Osage tribal leaders made a formal request for help and paid $20,000 to the Department of Justice. Meanwhile, guardianship for Native Americans didn’t end until 1934, despite extensive evidence of abuse. In modern times, Fletcher writes that Congress has generally waived immunity so that Native people could sue the federal government for the mismanagement of Indian assets.

Outside this context, the contemporary use of guardianship offers a necessary system of protection for those who are actually vulnerable, including children, people with diagnosed dementia or people who are incapacitated. Over the years, AARP, the seniors’ lobby, has worked to ensure that states require due process for establishing guardianship (called conservatorship in some states). And even now, guardianship can sometimes be abused. As “Marketplace Morning Report” has reported, most financial exploitation of seniors is not by unknown scammers but by family members, another argument for guardianship systems with strong oversight.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.