As ransomware and other cyberattacks grow, cyber insurance struggles to keep up

As ransomware and other cyberattacks grow, cyber insurance struggles to keep up

Given the prevalence of hacking incidents — before and after the Colonial Pipeline breach — more and more companies are purchasing cyber insurance to manage their risk. But are the pockets of large insurance companies deep enough?

A new report from the Government Accountability Office looked at the client list of a major insurance broker and found that the number of companies that bought policies grew from 26% to 47% over a four-year stretch.

Insurance gives companies that get hacked access to money for paying ransom.

“If you do have insurance, you can look at the policy and see what they’re gonna pay up to,” said ransom negotiator Tony Cook, head of threat intelligence at GuidePoint Security. “That helps you go to the table with a little bit of knowledge of what you can work with.”

Thing is, there so many attacks these days. So for insurance companies, it’s like covering a bunch of teenagers with sports cars.

“Now with ransomware and some of these other attacks,” Cook said, “it’s almost like you just handed everybody the keys to a Ferrari on the autobahn and said, ‘Good luck.’”

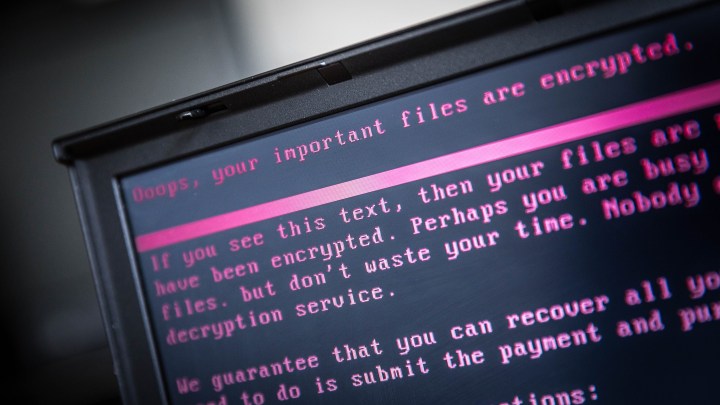

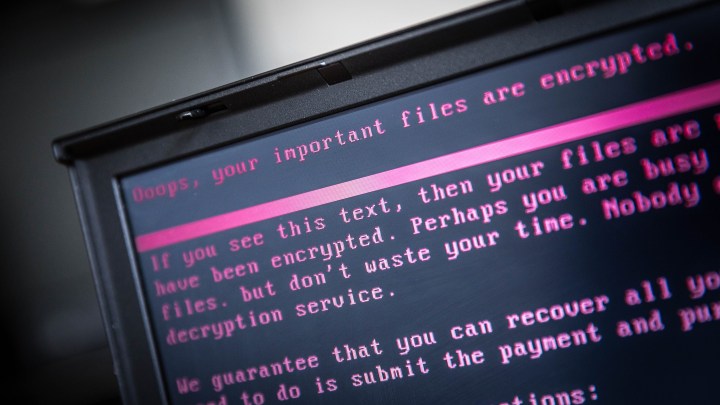

What’s driving all this, as it were, is how lucrative cybercrime is. A hacker lures an unsuspecting worker to click on a link, locks up everything on the company network, then demands money in exchange for the key.

The annual global cost of cyber breaches may be double that of natural disasters, the GAO report said, citing the Geneva Association, a think tank for the insurance industry.

“The more people pay ransoms, then the more people will conduct ransomware,” said Josephine Wolff, a cybersecurity policy professor at Tufts University. “As more of these attacks get launched, and we think maybe about half of the victims pay ransoms, there are more people interested in getting into this type of crime.”

Especially when there are very public events. Four years ago, the so-called NotPetya attacks crippled the drugmaker Merck, the company that makes Cadbury chocolate, a division of FedEx and the shipping giant Maersk. Total estimated cost: $10 billion.

“It’s one of these incidents that spurs so many claims that insurers start feeling like, ‘We’re not gonna be able to cover all of these. There were too many people affected. It was too expensive. We need to not be on the hook for all of this,’” Wolff said.

According to an April estimate from credit-rating agency Fitch, for every dollar an insurance company made in cyber premiums, it paid out 47 cents in claims two years ago. Last year, payouts jumped to 73 cents.

“Cyber policies generally were very profitable in the early days,” said Vincent D’Agostino, head of cyber forensics and incident response at the cybersecurity firm BlueVoyant. “The advent of ransomware has completely turned that upside down.”

So the industry responded.

“There are corresponding moves to raise prices,” said Philip Edmundson, founder and CEO of Corvus Insurance. “To non-renew accounts considered too risky, to scale back on certain terms of coverage.”

The average cyber policy costs $1,485 per year, according to AdvisorSmith Solutions, an industry research group. Insurers price products based on risk, and in general they rely on historical data, such as how much car crashes or windstorms have cost in the past.

“But in this case, that is not so helpful,” Edmundson said, “because the threats are increasing and the severity of the threats are growing, and we don’t have a good sense of where that ends.”

Think about it: What if a hack took down Google? Verizon? The power grid?

“We are trying to predict a weather that hasn’t happened yet,” said Julie Bernard, insurance sector leader for cyber-risk services at Deloitte.

“There really still is not enough money in the marketplace,” said Jon Bateman, cybersecurity policy fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “If there were a devastating cyber event on the scale of a hurricane, we would probably have to ask Congress to pass some kind of emergency appropriations the same way they do after Hurricane Katrina.”

Given this risk that’s bigger than even the insurance industry can handle, experts say things have to change. The government may have to ban ransom payments to deter the bad guys. Or force companies paying ransoms to report them, so there’s data.

For now, though, reforms are moving slowly because there isn’t enough urgency, Bateman said. “Nothing is exploding yet.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.