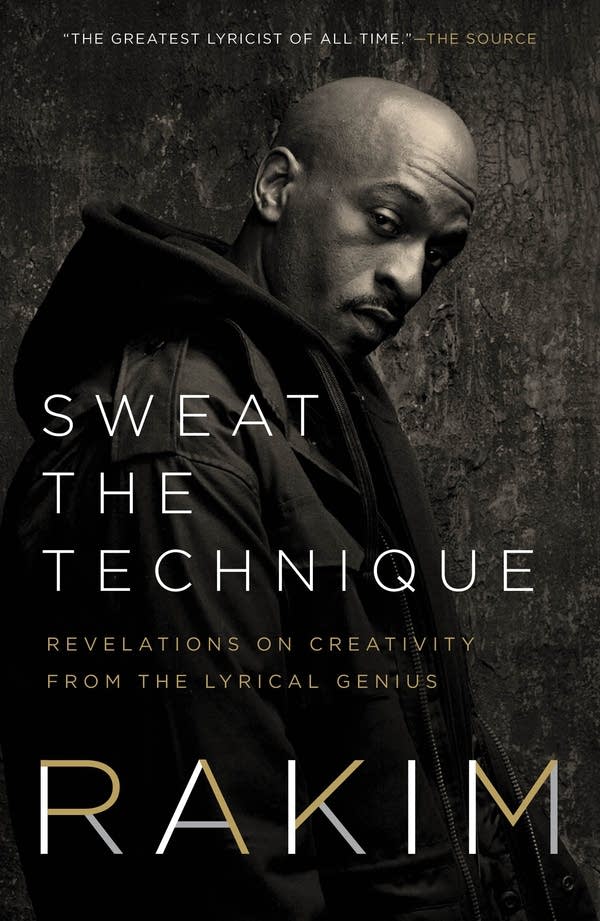

Thoughts on creativity from lyrical powerhouse Rakim

The influential emcee reflects on his life, his creativity and his career.

The following is an excerpt from “Sweat the Technique: Revelations on Creativity from the Lyrical Genius,” a memoir by hip-hop lyricist Rakim. Click the audio player above to hear Rakim’s conversation with Kai Ryssdal about finding his own style and the advice he’d give to newer artists.

I was six the first time I saw hip-hop. It was the summer of 1974. My big brother Stevie took me to see it. They didn’t call it hip-hop or rap back then, but it was already a lot more than just a sound. It was a whole experience. Late at night, in Wyandanch Park, they had a DJ with a big sound system that was plugged into a street lamppost and B-boys dancing and guys on the mic spitting little rhymes. These guys were the early rappers, and these parties were the beginning of hip-hop. The parties were happening in the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn, uptown—all over New York. DJs were taking disco, soul, and funk records—anything that was high-energy and powerful and danceable—and isolating the breakdown, the part where it’s just rhythm, percussion, and drumming that makes people want to dance with some force. Any record could become part of a rap DJ’s set because DJs weren’t concerned with the whole record. They focused on those breaks and mixed two copies of the record back and forth so they could extend the break and change the power of the record entirely.

I always believed there was a hip-hop way of thinking, because listening to this music was like taking musical steroids. It was sonic confidence.

Everyone learned the sonic power of the break from DJ Kool Herc, a Jamaican immigrant from the South Bronx who started spinning parties in the rec room of the building where he lived. In August of 1973 his sister Cindy wanted money to buy clothes for school, so she told Herc to throw a party and charge admission. Down in that rec room he became one of the fathers of rap. He had a big system with Godzilla-sized Shure speakers, so his music was loud. He spun on the breaks and sometimes he got on the mic and said little rhythmic phrases into an echo chamber. Stuff like “Kool Herc! Go to work! Go to work!” Simple stuff. “Y’all feeling all right?! To the beat, y’all! B-boys, are you ready? B-girls, are you ready?” He said “B” for “break,” for the dancers who’d go off on the breaks. They weren’t rhymes. They were like the zygotes that were the beginnings of the monster that would become MC’ing.

Herc spun parties all around the New York City metropolitan area, including on Long Island at Wyandanch Park. I was really young, but I was there, and I can still see his gigantic speakers that looked like fifty-five-gallon garbage cans. They were so loud they shook the ground like the music was creating an earthquake. Herc went all around the city, spreading the gospel of hip-hop. His formula was to extend the breakdown part so the serious dancers could get down and perform for the crowd. It wasn’t music meant to get boys and girls dancing together. It was music meant to get boys dancing instead of fighting in gangs. New York had a gang issue before early rap came along, and it mostly ended when the gangsters transitioned into music. A lot of early dancing was about warring crews battling by break-dancing without ever touching each other. Symbolic violence was a lot better than killing. But the new culture scared most club owners, so Herc and the other pioneering hip-hop DJs were playing for people who loved the music and would follow it anywhere. They went into the parks, and at those parties they started building a culture.

It quickly became a way of life for a lot of people in the hood in late-1970s New York City. The culture stretched beyond the music and included break-dancing or B-boying and graffiti art, and you could dress hip-hop with a Kangol hat and Adidas shell toes or Puma Clydes. I always believed there was a hip-hop way of thinking, because listening to this music was like taking musical steroids. It was sonic confidence. It made you bop harder, stand up straighter, stick your chest out more. It fed your ego. At a time when a lot of people in the hood were getting strangled by poverty, hip-hop came along and offered a boost of confidence and a jolt of fun. It was music from the hood for the hood, meant to make people feel good. And it spread like wildfire. In my elementary school years, everyone I knew around my age loved hip-hop. It was almost like the shared religion of our tribe. I loved every aspect of the culture and tried my hand at all of it. When I wasn’t trying to DJ, I would pop-lock with my friends for hours, then go get the canvases out and do some graffiti, then get with some rappers and kick freestyles. As soon as I knew what rap was, I was in love.

Once, Maniack, a local DJ who was friends with my brother Stevie, brought his equipment to our house. I was so young I wasn’t really tall enough to reach the turntables. Stevie and him sat there drinking beers and spinning records while I watched every little thing they did. I microscoped the whole situation. Stevie and Maniack decided to run out to get more beer, but first they took the needles off and hid them. They were hiding them from me, but I knew where they put them. As soon as I heard the front door close, I went over to the shelf, reached behind the picture frame, and grabbed the needles. I pulled out two milk crates and stood up on them to screw on the needles, and I got some records going and started trying to cut back and forth between them, but somehow I hit the pitch control knob so one of the records started going really fast, and I didn’t know how to change it. I panicked a little because the sound was going crazy. Before I came up with a solution, my brother and Maniack walked into the room and looked at me like What the hell is going on?

“Boy, get off them turntables! Stop playing around!” Stevie yelled.

“Nah, man, let him finish,” Maniack said, more curious than angry. “I wanna see what he does.”

He showed me how to change the pitch so the record played at the right speed, then I was able to chill out and start mixing. I was so good they were shocked at how much I’d picked up just from watching them.

I was seven when I wrote my first rhyme. I had seen guys on the block rhyming and wanted to try it. I wrote, “Mickey Mouse built a house / he built it by the border / an earthquake came and rocked his crib / and now it’s in the water.” Now I had the DJ’ing bug. With some life experience and some work on my vocabulary, I could start bringing things together.

Adapted from “Sweat the Technique: Revelations on Creativity from the Lyrical Genius” for Life Copyright © 2019 by Rakim. Published by Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.