Why doesn't the U.S. have a wealth tax?

A wealth tax could raise a lot of money and burden a privileged few. Trouble is, the U.S. Constitution basically bans it.

The U.S. has been home to some weird taxes: There have been taxes on tattoos, playing cards, wild blueberries, and hot air balloons. Missouri even tried out a bachelor tax on single men in the 1820s. But the federal government gets most of its money from the income tax administered by the IRS.

“I'm one of the few people out there who is a fan of the IRS,” says Janet Holtzblatt, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. She said she actually loves filing her taxes. “Oh my god, yes! I used to coincide doing my taxes with the Oscars. So two of the biggest thrills in my life.”

Holtzblatt gets excited about all the good her taxes will do for society.

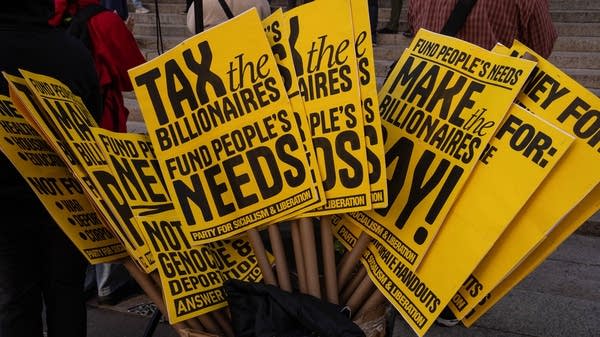

Recently there has been a lot of discussion of a different kind of tax: a wealth tax, which is, essentially, a tax on property instead of income. In a lot of ways, this makes sense. Many of the wealthiest people don't make a big income; their money is tied up in houses, or stocks, or superyachts, or art collections. That's got politicians like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren calling for a tax on wealth.

There's just one problem: A wealth tax is basically banned by the Constitution. The line in question: “Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states." It doesn’t sound like much, but it essentially means if the government were to collect a wealth tax, it would have to make sure the amount of money coming out of each state from the tax was in exact proportion to the population of that state relative to the national population. “Even with AI, the math is just impossible,” said Beverly Moran, a law professor emeritus at Vanderbilt University.

How did that line get there?

“When we think about how the Constitution came to be, there was a long struggle,” explained Moran. “North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia… What did all those states have in common? They were slave-holding states. They were agricultural states. What they were afraid of was taxes on land and taxes on slaves, both of which would be wealth taxes.”

In order to get the Southern states to sign on to become part of the union, the northern states agreed to essentially ban federal taxes on property. States and localities can tax wealth and they do: property, cars, boats, business equipment. But nationally, it’s a no can do. As a result, Jeff Bezos didn't pay any federal income taxes in 2011 and Elon Musk didn't pay any in 2018.

That doesn’t not sit well with Beverly Moran. “Why is there no wealth tax in the United States? If this is a democracy, why is there no wealth tax?”

After all, Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax proposal claims the tax (on those with more than $50 million) would only affect about 75,000 households in the U.S. and could bring in a lot of money.

Moran said as it stands, the Constitution would have to be amended for that to happen, or a Supreme Court ruling would have to allow it. But even if that happened, Janet Holtzblatt of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center isn’t convinced it would work.

“A wealth tax is really, really difficult to administer,” she said. “And that's been the challenge for many European countries that have tried to do wealth taxes in the past.”

In 1990, 12 European countries had a wealth tax in place. Only three of them still do. Holtzblatt said one reason for this is that countries that put a wealth tax in place — even a really small wealth tax — saw people's reported wealth drop off a cliff. In Switzerland, a 1% wealth tax eventually resulted in a 43% reduction in reported wealth. Some ultra wealthy people just moved countries to avoid paying; that's reportedly part of what prompted France to cancel its wealth tax.

Also, figuring out how much people should pay isn’t easy. Income tax is very straightforward: You take a percentage of somebody's paycheck. But how do you figure out the value of a Rembrandt, or a wine collection, or a Louis XIV footstool? It requires specialists and time.

“And that raises policy and administrative issues,” said Holtzblatt. Those issues that require manpower, which is a tall order these days. The IRS has just had its budget cut by 20% and its staff reduced by about 25%.