Teachers still haven’t recovered financially from the recession

Teachers still haven’t recovered financially from the recession

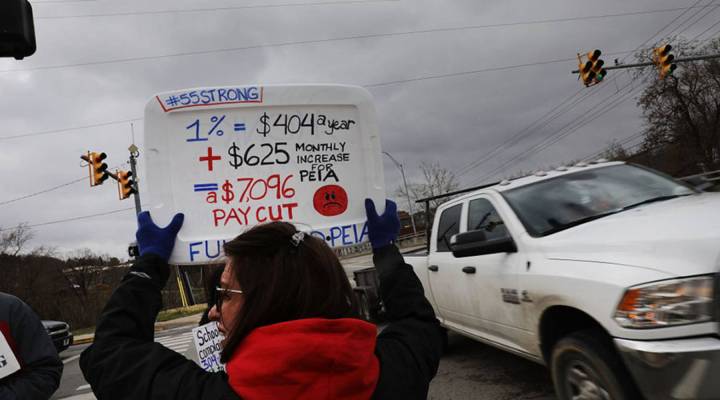

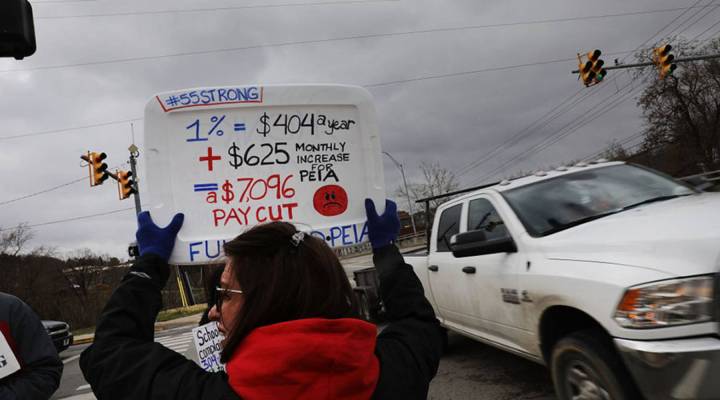

In recent weeks, teachers have been protesting, staging walkouts and marches in Kentucky, Oklahoma, West Virginia and Arizona. Teachers are upset about working conditions, pay and benefits, which in some cases have been stagnant or worsening for years.

One major contributing factor is recession recovery — 29 states have less funding per student now than they did in 2008. And with about 60-65 percent of school funding going to teacher salaries, that’s meant pay and benefits cuts and wage stagnation that doesn’t take into account years of experience or cost of living increases.

Nancy Belinge, a high school history teacher in the Orange Unified School District in Southern California, said she and her colleagues took a pay cut from 2008 to 2015 in the form of fewer paid work days.

“It was really hard to make ends meet at home, raising three kids,” she said, “It was difficult.”

Belinge’s district did give teachers a 2 percent raise in 2016, and old textbooks are now being replaced with new editions. But Belinge says she still worries about her financial future — she had to sell her house and start renting. In the last year, her health insurance out-of-pocket costs have doubled.

Each state and district handles school funding differently. Mike Griffith, a school finance consultant at the nonpartisan Education Commission of the States, said that during a strike, there’s a lot at stake for both teachers, the districts and the states.

“Coming out of the recession, I think a lot of states were thinking that they’d have additional dollars to fill the cuts that they made,” Griffith said. States rely on sales tax revenues for some school funding, and those taxes haven’t picked up in the decade since the recession began. “The money just hasn’t been there,” Griffith said.

The result? Flat spending or reduced spending. That means lower salaries or stagnant salaries, reductions to benefits and, often, declining conditions in the classroom — those beat-up textbooks and ancient computers you might have seen in teachers’ posts about the strikes.

Another big side effect of slow recovery from the recession is that it’s harder to find teachers. Griffith said that teacher shortages have moved beyond the norm.

“There’s always been a difficulty in smaller school districts in this country to get a qualified math teacher, science or special ed teacher,” Griffith said, “but they’re starting to see these shortages across the board, and we’re also starting to see it in larger districts or suburban districts that haven’t had these problems.”

Many teachers say they don’t have the resources they need in the classroom. Maggie Maslowski, anEnglish teacher from Joliet, Illinois, started her teaching career in a private school in 2003 teaching kindergarten through eighth grade. She made $19,000.

“If I wanted to decorate my room, I would have to buy my own stuff,” Maslowski said.

Some parents at the school were in a position to make donations and ease the burden, but the pay just wasn’t enough. In 2007, Maslowski moved to a public school, and things got better. Her salary doubled, but the financial crisis brought about changes.

The state stopped paying for buses for field trips. And spending on new technology was also put on hold.

Maslowski recognizes that even with these issues, the situation at her school is better than most. Teachers receive annual raises and health insurance, although out-of-pocket expenses have increased.

Teachers who are striking in their districts and states risk lost wages and, in some cases, being fired.

There’s a lot on the line for states, too. Griffith, the school finance consultant, said that states have done a lot of budget maneuvering to try to come up with funds for schools while avoiding tax increases. What they’re trying to figure out, Griffith said, is “‘How do we solve this problem without additional dollars?'”

If you would like to share your thoughts about the impact of state funding on teaching, email weekend@marketplace.org.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.