Building a diverse workforce by investing in college

Shayla Thacker had a rough start at the University of Minnesota. There were the usual freshman adjustments, like living away from home for the first time and a heavier workload.

“Then in the classes, there’s not too many students that kind of fit my profile,” she said.

Thacker, now 22, is African-American and was raised by a single mother whose income fell below the poverty line. She’s also the first in her family to go to college.

“Just finding other students to relate to, it wasn’t a natural process to connect with some of my peers,” she said.

But Thacker had one big advantage. She was part of a scholarship program aimed at reshaping Minnesota’s workforce. Along with $4,000 a year for school, she was paired up with a professional adviser to help get her through college.

“She went above and beyond to make sure I stayed in school,” Thacker said. “I knew that, wow, I really have someone that is invested and really cares about my success.”

The scholarship program is called Wallin Education Partners. It was created more than 20 years ago by the late Winston Wallin, a businessman who’d made his name at Pillsbury.

“It was obvious to Win that there was a demographic problem coming for the workforce,” said Steve Lewis, an economist and chairman of the board.

What Wallin saw coming was that the numbers of black, Latino and immigrant students in the state were growing, and too many of those students were not making it through school. Though Minnesota has been known as having one of the better school systems in the country, the educational achievement and attainment gaps for students of color are among the worst. Around a quarter of black and Latino adults in the state have college degrees, compared to half of white adults.

“We’re going to have a major deficit of college and university-trained people if we don’t do something about the high school and college completion rates for the current demographic of students,” Lewis said.

To qualify for a Wallin scholarship, high school seniors in the Twin Cities need at least a B average and a score of 19 out of 36 on the ACT. Their families have to earn less than $75,000 a year, though the average is less than $25,000. And, this is key: Unless they choose one of the country’s historically black colleges, they have to enroll in a school in Minnesota or one of its neighboring states.

“What we were really interested in is homegrown talent, and if a student goes to college in the five-state area, they tend to stay in our community and work and live here,” said Susan Basil King, executive director of Wallin Education Partners.

Fostering the local workforce is part of Wallin’s pitch to a growing list of corporate partners. Fortune 500 companies like General Mills and U.S. Bank, as well as medical device maker Medtronic, now fund a crop of Wallin Scholars each year and offer them paid summer internships.

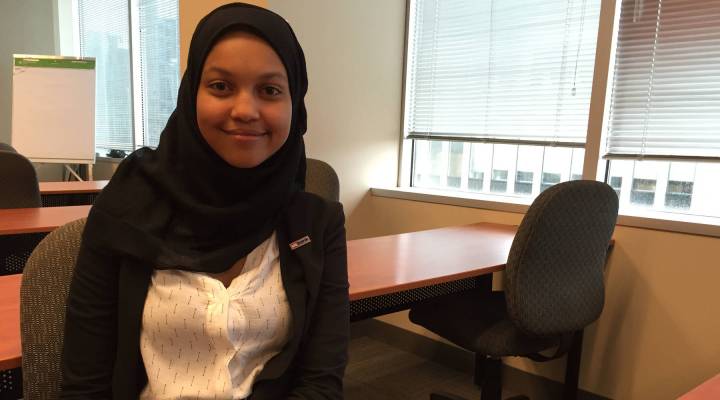

At U.S. Bank, Fatima Ahmad, 18, sits in a row of interns in the wealth management department, sifting through market data in an Excel spreadsheet.

“I had no idea how to do this four weeks ago,” she said.

Ahmad just finished her first year at the University of Minnesota. The daughter of Somali refugees, she stands out in her long skirt and headscarf in a sea of young white guys in collared shirts.

“My summer has been filled with doing everything from marketing to data entry to analyzing revenue,” she said. “Being able to help on that is an experience that you don’t get to have in college per se.”

More than 90 percent of Wallin Scholars graduate from college, according to the program. For companies like U.S. Bank, the hope is that students like Ahmad will come work there after they finish their degrees. The investment isn’t philanthropy; it comes out of the bank’s talent development budget.

“Diverse organizations make more money, are stronger, have better results — also have better working environments and more engaged employees,” said Jennie Carlson, U.S. Bank’s executive vice president of human relations. “For us, the customers of the future and our workforce need to match.”

Right now, they don’t. Despite its efforts, U.S. Bank is still predominantly white, especially at the top. Business leaders say recruiting minority employees from out of state can be tough. After a few winters, many don’t stay. But out of the 4,000 Wallin Scholars who’ve graduated since the program started, 80 percent are still living and working in the Twin Cities.

Shayla Thacker, 22, landed a full-time job at U.S. Bank after graduating from college in May.

One of them is Thacker, who talked about the isolation she felt her first year of college. She finished her degree in May and landed a full-time job training to be a commercial loan portfolio manager at U.S. Bank.

Her office on the 22nd floor of the U.S. Bank tower has a sweeping view of downtown St. Paul. Inside, she has pictures of her younger siblings. Thacker helps her mom support them by paying for things like summer camp and school clothes.

“They definitely help motivate me to really push for success and be their example,” she said.

Minnesota could have lost Thacker. She had planned to go to college out of state, but turned down Georgetown and Penn to go the University of Minnesota.

“The more time that I spend here, I see the more benefits of it,” she said. “I like to say that maybe one day I’ll just get a winter home somewhere, but I can stay here for the rest of the time.”

Just what Win Wallin was hoping for when he started the program in 1992. And he lived to see, very directly, the impact of his investment. When he was being treated for cancer six years ago, at the end of his life, one of the doctors he met in the hospital had been a Wallin Scholar.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.