47 economists filed an amicus brief in Trump's tariffs case. What'd they say?

Having a trade deficit isn’t actually that major of a problem, the economists argue.

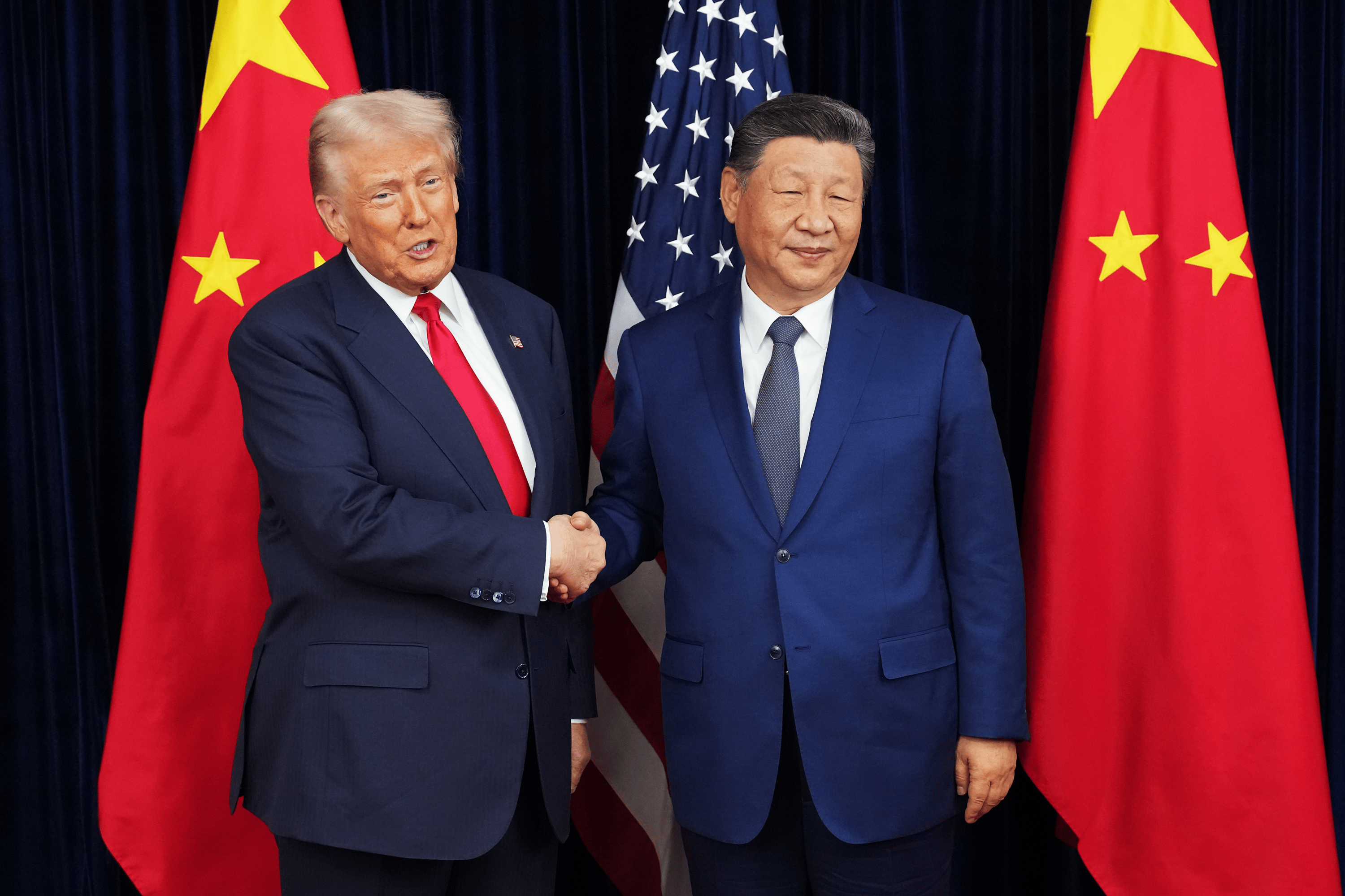

Presently, there’s a closely-watched case at the Supreme Court that deals with the legality of President Donald Trump’s tariffs by calling a trade deficit an emergency.

One of the friend of the court, or amicus curiae, contributions to the high court's understanding came from a group of 47 economists from across the ideological spectrum, including four Nobel laureates in economics, two former Federal Reserve chiefs, and one Treasury Secretary.

To help understand a teachable moment embedded in the amicus brief, “Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio was joined by Marketplace correspondent and host Sabri Ben-Achour. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

David Brancaccio: Sum it up. What is the basic argument that this group of hotshots are making?

Sabri Ben-Achour: They are basically trying to take down the economic rationale for these tariffs. In order for the president to exercise these powers under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, there has to be an emergency — something that is an unusual and extraordinary threat to national security or a threat to the U.S. economy. The emergency given by the White House — one of them — is trade deficits, and these economists say, "That is not an emergency. It is not unusual, and it is not a threat."

Brancaccio: But the administration argues — right, Sabri? — that trade deficits have hollowed out U.S. manufacturing, the idea that we import so much, and that cuts out demand for U.S.-made goods, and people lose jobs in the U.S., and our factories decline.

Ben-Achour: Trade deficits, these economists argue, do not have anything to do with that, do not have anything to do with a country's manufacturing base. If you replaced every single import with a U.S.-made good right now, the size of the U.S. manufacturing base, as a percent of GDP, would still be half of its peak from the ‘50s. And they point out that the U.S. doesn't actually manufacture less than it used to; it just does it a lot more efficiently and with fewer jobs.

Brancaccio: A big portion of the president's tariffs were based originally on the size of the particular trade deficit with a given country. Is this group of economists and a Treasury secretary and nobelists, they're saying that those two things are not connected?

Ben-Achour: Yeah. The level of tariffs that we have on other countries or that other countries have on us [are] completely divorced in the data from the trade deficit.

Brancaccio: Just so it's clear, because maybe it seems somehow dangerous to send money out of the U.S. to buy imports, more money than some foreign countries send to the U.S. for "Made in the USA" goods and services, isn't that something that's broken that a president should fix?

Ben-Achour: Yeah. It sounds like it, right? But there's a quote from Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow that these economists refer to. He said, "I have a chronic deficit with my barber who doesn't buy a darn thing from me." They say that to demonstrate it is OK to have a trade deficit with countries, it's normal. The specific reason it is OK is that all that extra money we spend to buy stuff from the world, we get it back. That money comes back to the U.S. in the form of investment in U.S. companies, in U.S. Treasuries, and other things. So, a trade deficit is actually another way of saying the world is investing a lot in the U.S.

Brancaccio: We've been talking about this group of famous economists and so forth who are lending their two cents to the case. Do you think these arguments might make their way into the Supreme Court's eventual decision?

Ben-Achour: Well, I am not a constitutional lawyer, but the administration argues that its rationale for declaring an emergency is just not reviewable. And even Justice Sotomayor conceded that declaring an emergency would be an area where the administration gets a lot of deference. I would just add that this brief is basically implying that nearly the entirety of this tariff policy is based on a misunderstanding of international economics.