With China no longer buying, U.S. soybean farmers face tough choices

China is typically the destination for over a quarter of the U.S. soybean harvest. Now, U.S. farmers have a choice between selling at lower prices domestically or storing crops in hopes of a trade deal.

The U.S. soybean harvest is here. According to the USDA, 5% of this year’s crop is already out of the ground and the agency is forecasting record yields.

Where all that soy is headed is a different question. China, typically the destination for over a quarter of it, still is not buying.

It’s day two of the soybean harvest on Brian Warpup’s 4,000-acre farm. This morning, he was behind the wheel of a semi-truck.

“Yeah, I am literally hauling soybeans to market, yes,” Warpup said. From Warren to Decatur, Indiana. Don’t worry — he’s got both hands on the wheel.

Normally he’d sell just about all of his soybeans straight off the farm after harvest. “However, with the subdued prices that we have right now, I kind of want to store them a little bit in hopes that price will eventually go up,” Warpup said.

Prices are low now because China, normally the top international buyer of U.S. soybeans, is sitting this harvest out so far.

Warpup’s family farm is scrambling to make room in its grain bins to store much of its soy crop by selling off its corn harvest early. He’s banking on a trade deal to make that worthwhile. But waiting it out isn’t an option for every farmer. They can’t just build new storage overnight.

“It’s hard to build a new bin right now because there's so much demand. So, there’s a bit of a supply chain shock,” said Kyle Jore, a soybean farmer in northern Minnesota.

He’s also an economist with the agriculture consulting firm Watts and Associates. If this waiting game goes on much longer, he said, storage will run out.

“For those producers that are in a really tight cash position or didn’t have a lot of working capital, it could be quite dire,” Jore said.

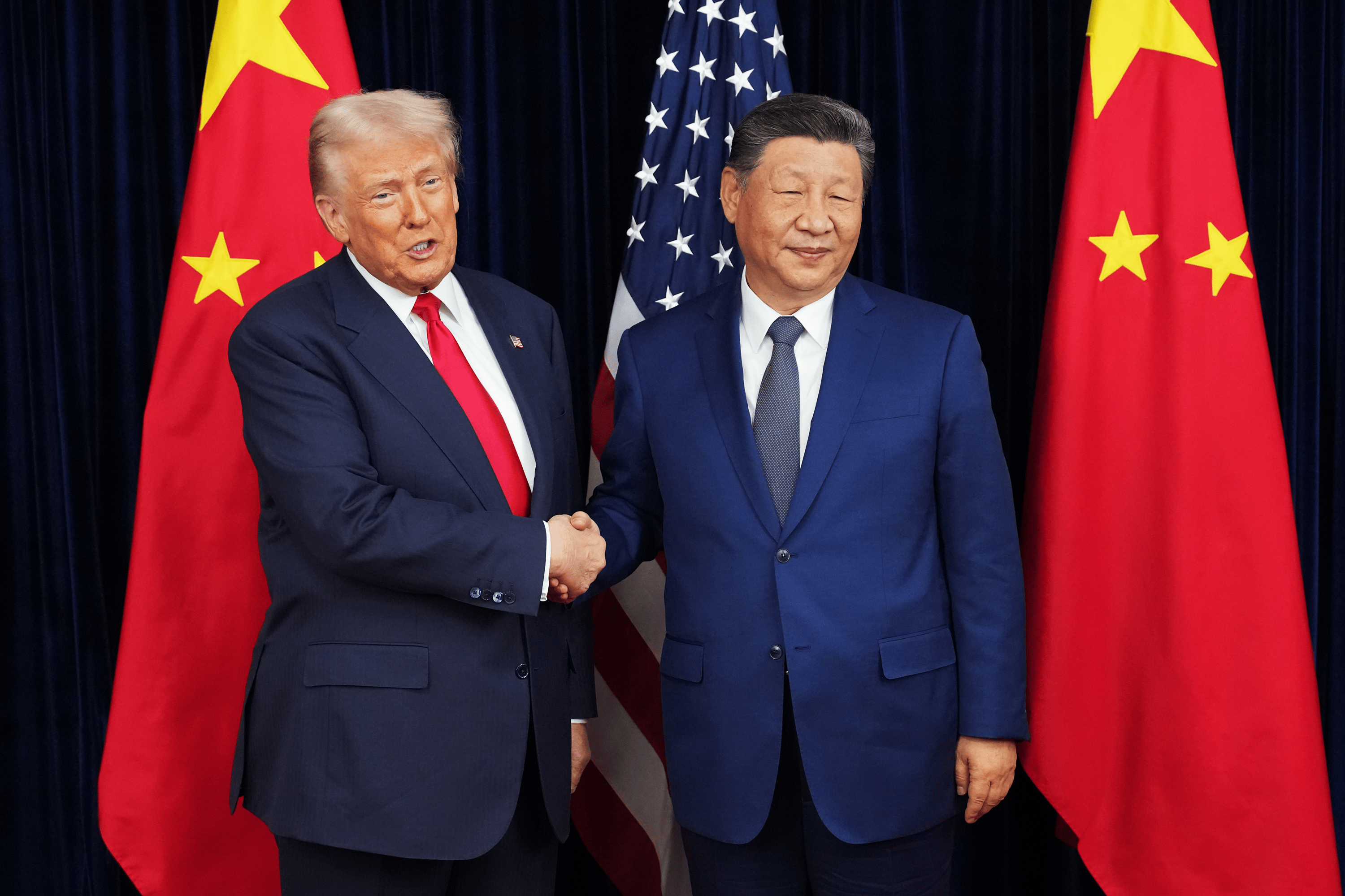

American farmers have been here before. Just like during President Donald Trump’s last trade war, some farmers are expecting the USDA to step in and make them whole.

“As much as you don’t want that to be the way that farmers make their money, I don’t think they’re gonna have a lot of choice,” said Jonathan Miller, a corn and soybean farmer based in western Kentucky.

Unlike last time, he said, farmers are also getting squeezed by inflated input prices.

“I suspect this could get ugly,” Miller said.

Ugly meaning farm bankruptcies and a stagnating U.S. ag sector.