Tariffs on products vs. tariffs on countries: an explainer

The Trump administration’s tariffs roughly break down into one of two categories. What do each of them mean for the global economy?

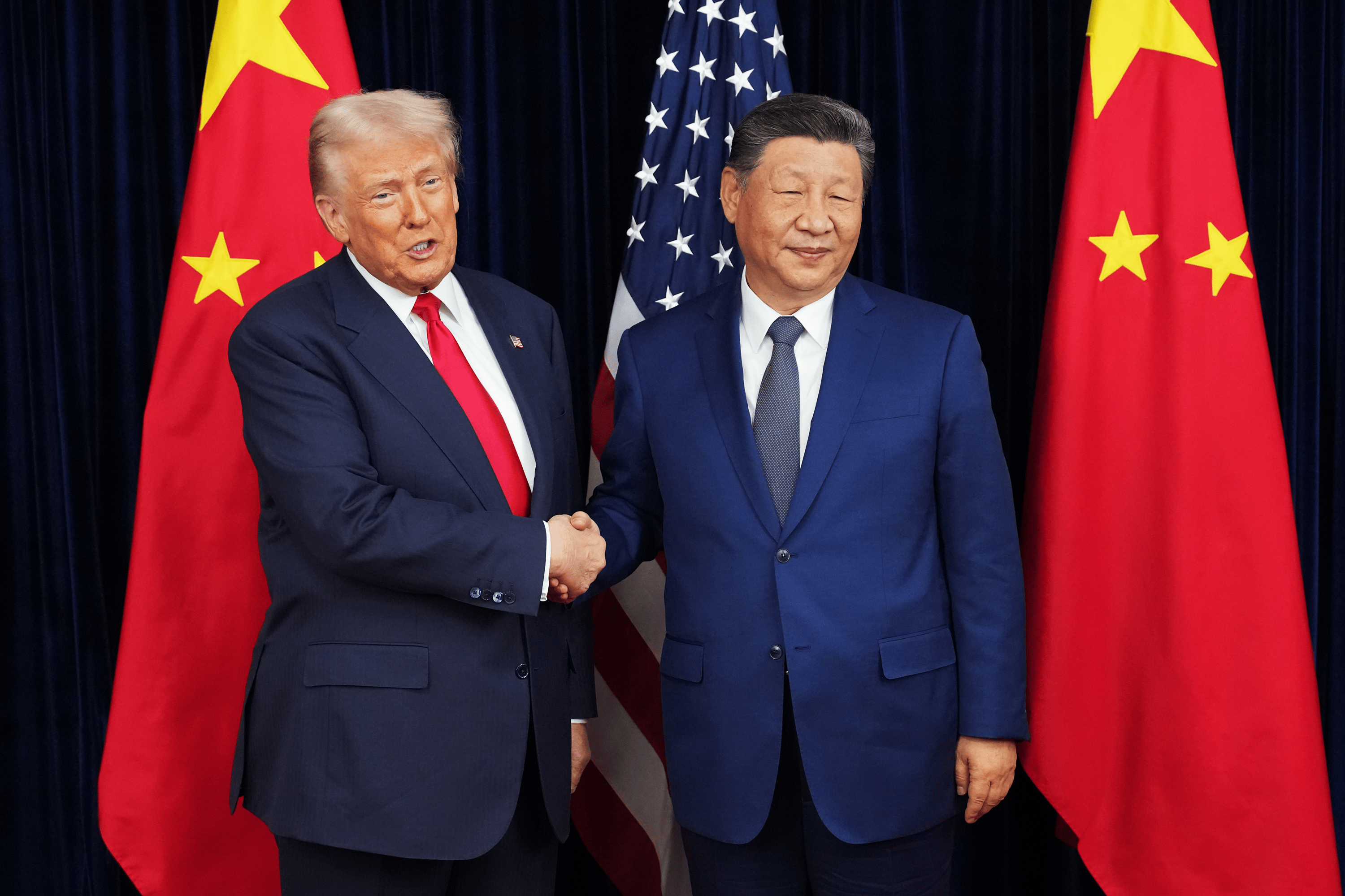

We can put the Trump administration's many tariffs into one of two categories: On the one hand, there are tariffs that target specific countries, such as stuff coming from China or Canada.

On the other hand, there are tariffs that target specific industries or products. Let's say steel, no matter where that steel is coming from. Do these different tariffs mean different things for our global economy?

For more, “Marketplace Morning Report” host Sabri Ben-Achour spoke with Doug Irwin, professor of economics at Dartmouth College. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Sabri Ben-Achour: Under the current administration, there are two types of tariffs. There's the tariffs on goods from countries — specific countries — and then there's tariffs on industries. Do one or the other of those carry more economic consequences than the other?

Doug Irwin: I’m not sure they would be different in terms of their consequences, but their implications are very different depending on the industry or depending on where you're sourcing from. The administration is considering a 50% tariff on imported copper. So what's interesting about that is we get much of our copper from Peru, Chile, and Canada. We have free trade agreements with all of those countries, so the 50% tariff is across the board. It doesn't matter where you're importing copper from, but it will hit those three countries, in particular.

Now, with the cross-country tariffs. So, for example, we're considering duties against Lesotho at very high levels and a lower duty on goods coming from South Africa. Well, if you're a textile producer in Lesotho, what you would probably want to do is just ship your goods to South Africa and then ship them to the U.S. to avoid the very high tariff on Lesotho goods, basically calling your goods South African goods.

Ben-Achour: The country-specific tariffs, the ones that we're about to get, they have been challenged in court, and the next court date on these, I believe, is July 31. How real of a possibility is that those country-specific tariffs could go away or be diminished in some way because of some legal ruling?

Irwin: You're absolutely right. The reciprocal tariffs that were announced on April 2 and have been paused, those have been challenged in courts. And, in particular, the Court of International Trade, which is a special tribunal in New York City that just hears these very narrow cases on trade policy, they ruled unanimously against those reciprocal tariffs. Now, of course, that's being appealed, and it might even go to the Supreme Court. We don't know whether those tariffs will survive, but let me just contrast that, just briefly, with the industry tariffs. Those are usually under different statutes of the law that allow the president to raise tariffs on particular goods if there's, say, national security justification for them, if those foreign products have been dumped or subsidized, and they're selling them to the U.S. And so those are on much firmer ground legally.

Ben-Achour: The goals of these tariffs are hard to pin down. You know, some days it's to raise revenue. Some days it's to bring back production and jobs. How likely is it that we would reshore production of these industries and get a net gain of jobs?

Irwin: In some cases, like copper, it's going to take years and years to make new investments and new mines to dig out the copper deep under the earth. So we might not see any jobs initially, but there might be plans for investments. Another factor here is that a lot of these industries are not going to bring back a lot of jobs if we stop imports, because they're very capital-intensive, or they're very technology-intensive.

So, to take steel, for example, today it's pretty much been automated and mechanized. Technology has taken over. So we can increase steel production in the U.S., but it's probably going to mean we're going to use existing plants and existing equipment, or bring on new technology that won't create a lot of jobs, per se, when we increase output.