U.S. shrimp industry dwindling from decades of foreign competition

Shrimp industry groups hope tariffs can help level out prices. But others are skeptical.

Shrimp are the quintessential Georgia seafood. But even though they’re ubiquitous on coastal menus, those shrimp often aren’t from Georgia.

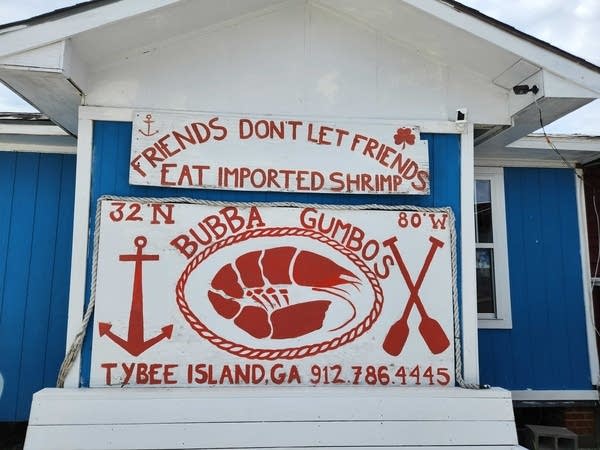

“You got pictures of shrimp boats on the wall and you're serving Indian shrimp — somewhat consumer fraud in my opinion,” said Jesse Petrea, a Republican state representative from Savannah.

Recent genetic testing on the shrimp at 44 Savannah restaurants revealed that 34 of them were actually serving foreign shrimp.

“Some people would say well, but they're, they're cheap,” Petrea said. “They are, but at what cost?”

The shrimping industry has a long and storied history in the Southeastern U.S. – but it’s in trouble. For decades, domestic shrimpers have struggled to compete with cheap foreign imports, and they’ve largely lost. Imported shrimp often cost $5 or less per pound. Wild-caught Georgia shrimp can go for more than $15 per pound.

Some are celebrating the prospect of tariffs on foreign shrimp, while other shrimp experts are skeptical.

Fewer than 200 shrimp boats are working the Georgia coast these days, down from around 1,500 in the early 2000s. That’s according to Marc Frischer, who studies the shrimping industry at the University of Georgia’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

“Even though the shrimp are doing very well, the shrimp industry in Georgia is not,” he said. “It's really declining. We're actually at risk of losing it.”

American shrimpers catch wild shrimp in the Atlantic Ocean from Florida to Virginia and in the Gulf of Mexico. Imported shrimp are typically farm-raised. That can have serious environmental impacts, from habitat destruction to waste and antibiotics leaking into the surrounding water.

Farmed shrimp are also available in much larger quantities, which drives down their price.

Frischer said local shrimpers are forced to sell their wild catch for less.

“They're really not the same product,” he said. “But the shrimpers, at this point, are getting that same price.”

At the same time, American shrimpers still have to pay U.S. costs for everything else — fuel, upkeep on their boats, insurance.

Former shrimper Charlie Phillips serves shrimp — only the locally-caught kind — at his seafood restaurant perched on the edge of one of Georgia’s coastal marshes. He said foreign competition is making shrimping untenable for Georgians.

“A lot of the shrimpers are losing dock access,” he said. “They don't have a place to unload.”

That’s because packing houses, the warehouse-like operations that process shrimp, often own the docks, and they’re shutting down. Phillips owns one of those packing houses next door to the restaurant, and even he doesn’t handle shrimp anymore.

“Prices were going down, expenses were going up, and it was just getting harder and harder to make it work,” he explained. “It's still hard to make it work.”

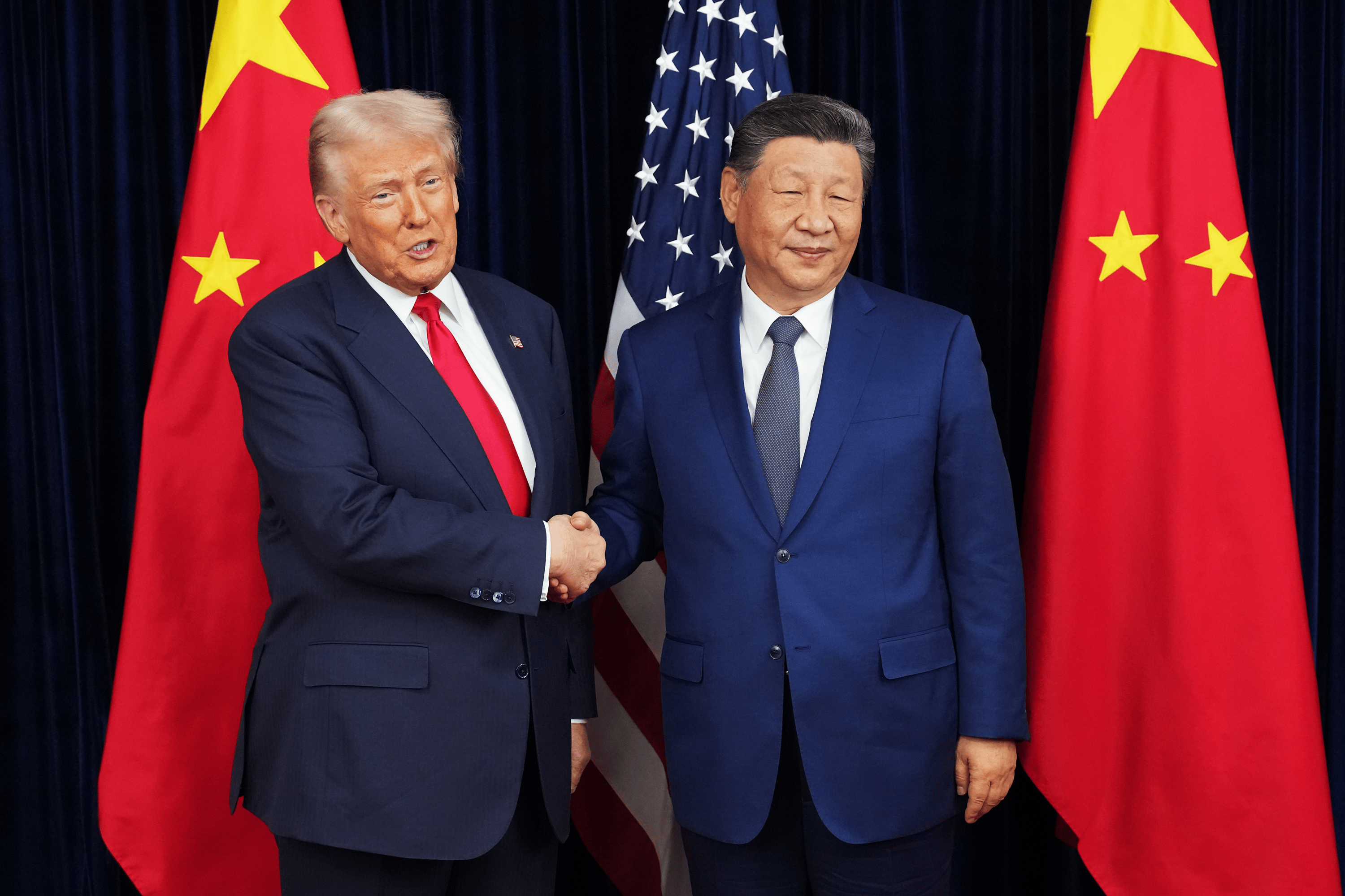

Fishermen and industry groups are hoping that the Trump administration’s new tariffs will help level out prices so Georgia shrimpers can compete. The highest tariff proposed for a major shrimp-supplying country is 46% for Vietnam. But here’s the thing: Even with that tax, imported shrimp would still be a few dollars less per pound than the wild-caught local kind. That’s why Phillips is skeptical.

“It's still going to be cheaper than domestic,” he said. “And for the most part, the customers are going to pay the price.”

For his part, Phillips said he’s determined to keep serving local seafood — to support the local economy and to keep people invested in the coastal environment where the shrimp live.