Tariffs will have an outsized impact on the apparel industry

It won’t be easy to move clothing assembly — or the manufacturing of fabric, buttons and zippers — to the U.S.

The signature product at the menswear brand 3sixteen is specialty jeans, the kinds made for denim nerds. And one thing that makes them unique is that they’re put together in the U.S.

“Early on in the brand, when we were still learning how to make jeans, there was a lot of value with being able to visit the factory to understand and really get acquainted with that process,” said co-owner Andrew Chen.

Unfortunately for Chen, even though his CS-100x jeans (which retail for $250) are assembled in San Francisco, tariffs are going to greatly impact the cost of making them. The actual denim fabric is made in Japan, which is known for selvedge denim, a labor intensive manufacturing process done on old school looms that give the fabric a finished edge. It’s not commonly made in the U.S.

“There’s a long and storied, over a century’s worth of history of textile development, of denim development, of indigo dyeing,” said Chen of fabric making in Japan. “It’s a part of their culture.”

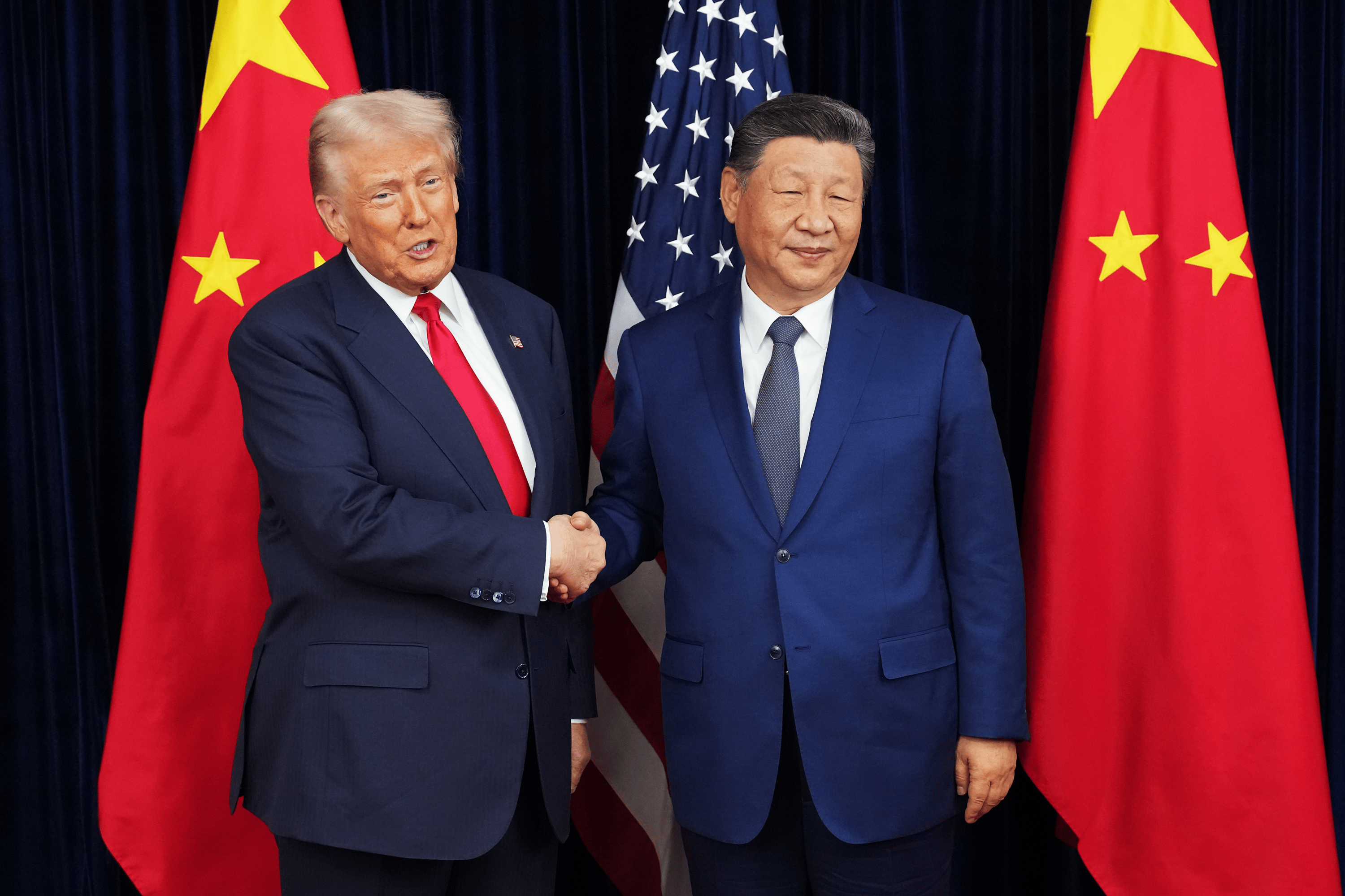

Tariffs are going to touch many, if not every industry that makes and sells goods in the U.S. But they’ll have an especially outsized impact on apparel. Something like 98% of clothing sold in the U.S. is imported from abroad, according to the United States Fashion Industry Association. The top supplier is China, which is subject to the steepest tariffs under President Donald Trump’s new trade policies.

And even if clothing brands want to assemble garments in the U.S., most textiles are made overseas in Asia. It’s a big reason why a lot of clothing is also manufactured there.

“They’re very good at what they do in apparel manufacturing,” said Phyllis Sevachko at apparel consulting agency Stateless Design & Consulting. “It’s skilled labor. They have all of those process steps nailed down.”

Chinese manufacturers are especially skilled at something called vertical integration. Basically, factories produce many components, like fabrics, buttons and trim, in house. There’s no calling one supplier over here to check on a shipment or calling another over there to make sure the thread will match. This saves companies a lot of time and money.

Tariffs are now complicating that equation.

“I’ve been working on costing for clients and I’ve seen it double and triple,” said Sevachko.

She said some apparel makers are looking to leave China and move production to Vietnam, India or South Korea. They are unlikely to come to the U.S. anytime soon. For one, that’s going to cost companies, and in turn consumers, a lot more because of labor.

“You know, we’ve been trained that we can get goods at such affordable prices,” said Sonia Lapinksy, who runs the fashion retail practice at AlixPartners. “It’s going to be really hard for consumers to swallow what it would take to afford locally produced product.”

Even if consumers are willing to pay higher prices, it would take years to move production to the U.S. Brands have to buy equipment, train workers and open up factories specializing in fabric, zippers, buttons and sequins; that takes a lot of capital. And to get there, companies would need trade policy certainty.

“And when there’s this much uncertainty, retailers are unlikely to make a significant capital investment until they are more sure about how things are going to sort out,” said Lapinsky.

For Chen at 3sixteen, there’s no way his small menswear company could afford to run its own fabric factory. He has just 15 employees. They’re expert designers, not experts at turning cotton into denim fabric.

“To open up our own manufacturing facility, that is its own skillset,” said Chen, who will continue importing from Japan and will likely have to raise prices to pay the tariffs. “We wouldn’t know where to begin or how to do it.”

Marketplace’s Jack Shields contributed reporting for this story.