Understanding the civil rights movement as a labor and economic movement

Understanding the civil rights movement as a labor and economic movement

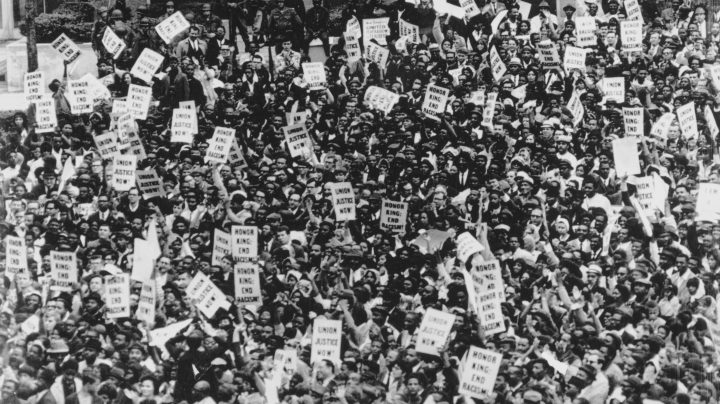

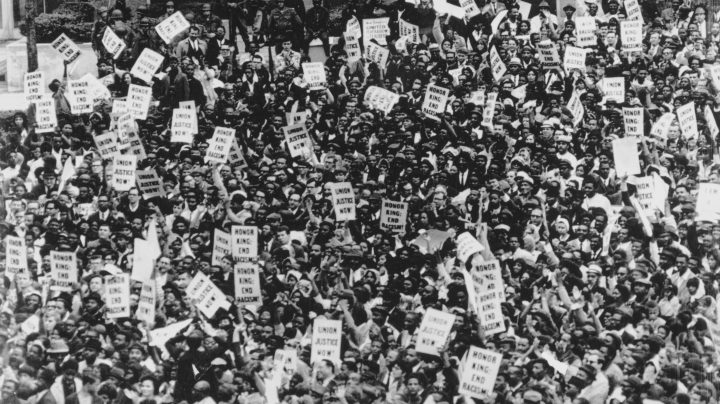

When discussing the civil rights movement, many focus on its political and social implications. But we rarely hear about the economic ideals that drove the movement. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech starts with an economic metaphor.

King describes the economic hardship Black Americans face:

“America has given its colored people a bad check, a check that has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’ But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.”

Nearly 60 years later, Black Americans are still waiting for the check to clear.

When reevaluating the civil rights movement, it becomes clear that economic justice is one of the topics many leaders emphasized. Robin D.G. Kelley, a professor of history at the University of California, Los Angeles, said the civil rights movement was also an economic and labor movement because “legalized segregation was an economic system. You know, it determined wages, determined job classifications, it determined where people can live. It even determined where you can go to school.”

The civil rights movement wasn’t just about attitudes around racism, but about access to good jobs, access to economic institutions and expanding workers’ rights. “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal spoke with Kelley about the labor and economic dimensions of the movement. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: A lot of the conversation — most of the conversation, I think — about the civil rights movement is about it as a political movement and as a social justice movement. Could you, in the first opening minute of this interview, give us the background of the civil rights movement as a labor and economic movement, please?

Robin Kelley: Well, the civil rights movement was always an economic movement because legalized segregation was an economic system. You know, it determined wages, determined job classifications, it determined where people can live. It even determined where you can go to school. And one of the big issues that was raised was desegregation. Desegregation was intended to end practices like taking Black people’s tax monies to subsidize white education. And finally, the Black community was a labor community. And it’s not an accident that Southern labor unions discriminated, but Black labor organizations fought for the right to equal wages, access to housing and fair rents — that sort of thing.

Ryssdal: What happened, though, at the national level to make the civil rights movement — and I don’t know, you tell me, I don’t know whether it was a conscious shift or something happened — but it became less economic justice and more political and social rights?

Kelley: I actually don’t think the civil rights movement ever left that agenda. And I could illustrate it. So if we think of the civil rights movement as extending well into the 1970s and ’80s, then we have to consider the National Welfare Rights Organization as civil rights, fighting to extend welfare rights and for basic income. And we have to remember, Coretta Scott King, you know, after her husband was killed, took up the fight for full employment. Full employment was one of the most important civil rights agenda items, and they got the passage of the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act. But what happened was that some of these initiatives died. They died when corporate interests in the Federal Reserve and members of both political parties agreed that the problem facing the economy was wage inflation. And wage inflation meant you solve it by crushing labor unrest, you solve it by reducing wages. And then it enabled companies to seek out cheaper labor outside the country. So I don’t know if I could say that the labor movement, or rather the labor agenda, completely disappeared.

What did happen, though, and one of the most tragic stories, I think, in all this, is that some Black elected officials took a stand. It was very opposite of what Dr. King stood for. I mean, one example: Dr. King died in Memphis [Tennessee] fighting on behalf of sanitation workers. A decade later, Maynard Jackson, who was very close to Dr. King, was mayor of Atlanta, and he faced a sanitation workers’ strike. And what did he do? He broke the union. And he got the backing of the NAACP and even Dr. King’s father, who ironically called the union outside agitators. And that was a foreboding of what was to come. The civil rights movement betrayed its agenda, you know.

Ryssdal: That’s such an interesting passage. The whole thing about Coretta Scott King and Humphrey-Hawkins and the thing that we talk about on this program all the time. The Fed chair going up to do Humphrey-Hawkins testimony and how it did all become about wage inflation. Let me ask you about something else you said, though, which is that the civil rights movement extends into the ’70s and ’80s. You just talked about Maynard Jackson and his role in civil rights in Atlanta and what he did in the sanitation strike there. Do you think there is a connection between the civil rights movement in this country of the ’50s and ’60s and what is happening now in this country?

Kelley: There is. The inheritor of the economic justice agenda of civil rights, I would argue, is the Poor People’s Campaign, led right now by Bishop William Barber and Reverend Liz Theoharis. They are leading a campaign, calling for, again, basic income, the restoration of welfare and really solving the problem of poverty through the redistribution of wealth.

Ryssdal: Let me ask you in a slightly different and perhaps a more pejorative way, if you’ll bear with me. So the civil rights movement of the ’50s and ’60s in this country — and look, I’ve only seen it in newsreels, as have you and I’m sure most people — it seemed to be ever-present in the news. I don’t think the Poor People’s Campaign has that presence in the national conversation, and, granted, the national conversation now is diffuse in many more ways, but I guess —

Kelley: You are so right about that.

Ryssdal: So does the movement now suffer from that?

Kelley: Well, the reason we don’t see the Poor People’s Campaign is because we are saddled with an understanding of the economy that’s based on growth. And that, you know, that wasn’t the civil rights agenda. That’s the antithesis of what Dr. King imagined when he said, “We need a revolution in values away from profit motives and property rights.” He made the speech in 1967. He says, you know, “True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that the edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.” That is the basic premise of the current Poor People’s Campaign, which goes against the basic premise of all the economic reporting — except for your show. But all the economic reporting we get, you know, is about how to grow the economy based on the current edifice, not restoring what we used to call the “social wage.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.