Mexican border town residents resilient despite pandemic isolation

Mexican border town residents resilient despite pandemic isolation

On an afternoon in early November, Beronica Ureste rode into the Rio Grande on horseback, pausing when she reached the middle of the river that marks the international border.

Ureste lives in Boquillas del Carmen, a Mexican town of about 250 people just across the river from Big Bend National Park in Texas. On her back she carried a bag of the crafts her community is known for: aprons and purses decorated with the flora and fauna of the borderlands.

“Ocotillos, roadrunners, donkeys — that’s what we sell,” she said, leaning over to show off the designs.

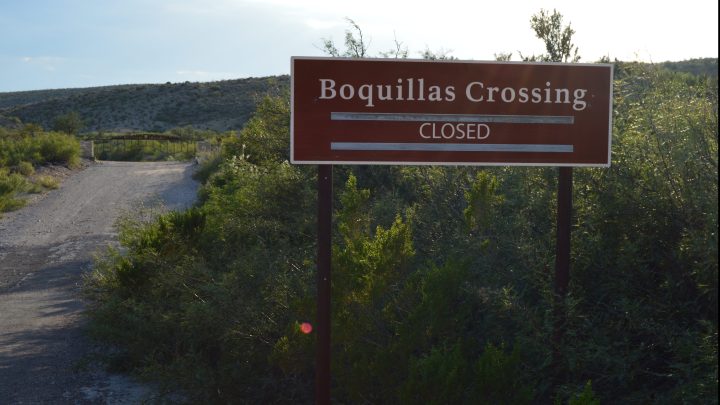

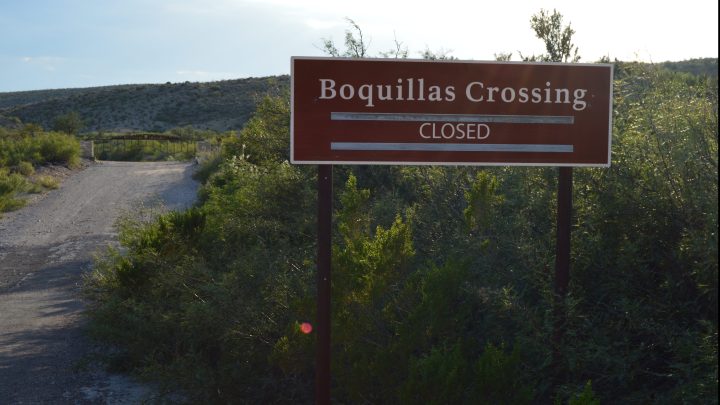

The aquatic rendezvous was a little inconvenient, but for much of the past two years, it was the only way Ureste could meet with Americans. Her town is connected to Big Bend at a small port of entry — a building just up the bank, staffed by park employees and monitored remotely by customs officers who check passports via video call. But in March 2020, the crossing shut down — a pandemic measure meant to protect both the rural village and visitors to the park.

At other ports, U.S. citizens and essential workers were still allowed to go back and forth. Here, though, that wasn’t the case. As Big Bend National Park Superintendent Bob Krumenaker explained, that’s partly to do with economics.

“Boquillas is probably the first to close and the last to open of all the ports, because from an economic point of view on a global basis, there’s not much going on,” Krumenaker said.

But for people like Ureste, the crossing is vital. Pre-pandemic, Boquillas played host to thousands of visitors a year: tourists from the national park who would cross in a rowboat and ride a donkey up to the village for a taste of rural Mexican life. So when the port closed, Ureste and her neighbors found themselves cut off from their financial lifeline.

They were also suddenly isolated. While the Rio Grande Village Store is just a few minutes up the road on the U.S. side, the closest grocery store in Mexico is four hours from Boquillas, in the city of Múzquiz.

“We are a community so far away from the other cities,” Ureste said. “And right now it’s hard.”

This wasn’t the first time Boquillas residents have been stranded. After 9/11, the crossing here was closed for more than a decade. More recently, when disagreement over funding for a border wall prompted a federal government shutdown, the port was closed for over a month.

The community has found creative ways to make ends meet. During the closure, some men in Boquillas crossed the river discreetly, putting crafts on the American side with coffee cans where tourists could leave payment. Other residents, like Ureste, moved their businesses online when the pandemic started to platforms like Facebook.

“First, I was very scared,” she said. “I barely used Facebook, and I didn’t know how to do it, even how to post.”

Over time, Ureste built up a clientele around Texas. Her father lives in the U.S., and throughout the pandemic, he regularly made the trip down through the nearest open port of entry — hours away — to pick up Ureste’s wares. Then he brought them back for buyers as far away as San Antonio and Dallas.

Neighbors near the river also pitched in to help.

“We raised about $20,000 that went toward emergency supplies and food, diapers, baby food, everything that they needed,” said Mike Davidson, who runs the Boquillas International Ferry, the rowboat that takes people across the river in normal times.

The U.S. government quietly lent a hand as well: Ureste said that over the summer, Americans in uniform beckoned Boquillas residents to the river’s bank to be vaccinated.

This spirit of help is what made the last two years bearable, Ureste said. Despite the challenges of living in Boquillas, she added, almost no one moved away. On Nov. 17, the border crossing reopened, and Ureste said she plans to stick around.

“I love my town,” she said. “I have gone out and lived in big cities, and I don’t like it. I love it here.”

Now, she’s eager to welcome visitors back to Boquillas — not online or from the river, but on dry land.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.