How the class history of Jell-O came full circle

Examining the rise and fall of a jiggly, wiggly icon.

For some, it conjures the image of sick days spent home from elementary school. For others, it’s associated with frat parties and keg stands. Still, for some, it’s right at home in those all-American ‘90s buffets that used kale as decoration rather than foodstuff.

I am, of course, talking about Jell-O. For me, the jiggles of Jell-O remind me of all of those things — but it’s also an image of home and family.

My Grandma Dawn (as she will introduce herself, no matter her relation to you) makes her signature Lime Jell-O Dessert each year. Sometimes, it’ll be a holiday treat or a birthday surprise or an addition to any lucky potluck. It’s not at every occasion, though likely would be if you asked nicely. It’s a recipe that Grandma Dawn got from her mother-in-law, and it helped her stretch her dollars while providing her children a sweet treat.

“I do remember using Jell-O a lot when I got married in ‘63 and had three kids to feed, and we were trying to make something pretty,” she told me. “You had to have the colors and stuff.”

She could dish up Jell-O for dessert after Hamburger Helper, another food item she chose for its convenience and affordability (one that’s making a comeback these days). And it’s not a coincidence: Jell-O has, for years, marketed itself to busy, working-class moms. But that wasn’t always the case.

Scroll down to see Grandma Dawn’s Lime Jell-O Dessert recipe.

The history

Before the likes of Jell-O brand gelatin came … well … just gelatin. One of the first recorded recipes for aspic, gelatin’s savory cousin, appeared in the late 1300s in the French cookbook “Le Viandier.”

Gelatin is derived from the structural protein collagen, which is found in the skins and bones of animals like pigs and cows. Those animal parts are boiled down until collagen can be extracted and formed into a gelatinous concoction. This process is incredibly time-intensive, though — it could take two days of work or longer to produce calf’s feet jelly, as it was called.

Because it took so long to prepare, gelatin was a dish reserved for the elites. And it would often be highly ornamental.

“That was a statement, just the way, if you bought a Porsche or a BMW today, or a Rolex watch, people would know you were rich,” explained Carolyn Wyman, the author of “Jell-O: A Biography.”

But then came the Industrial Revolution, and with it, more industrialized foods. Like instant gelatin.

The early days

In 1897, Pearle Wait, a resident of LeRoy, New York, created a sweetened, flavored gelatin dessert that his wife, May, called Jell-O. Wait sold the trademark, recipes, and patent for the Jell-O to Orator Woodward for $450, who founded the Genesee Pure Food Company and began mass-production.

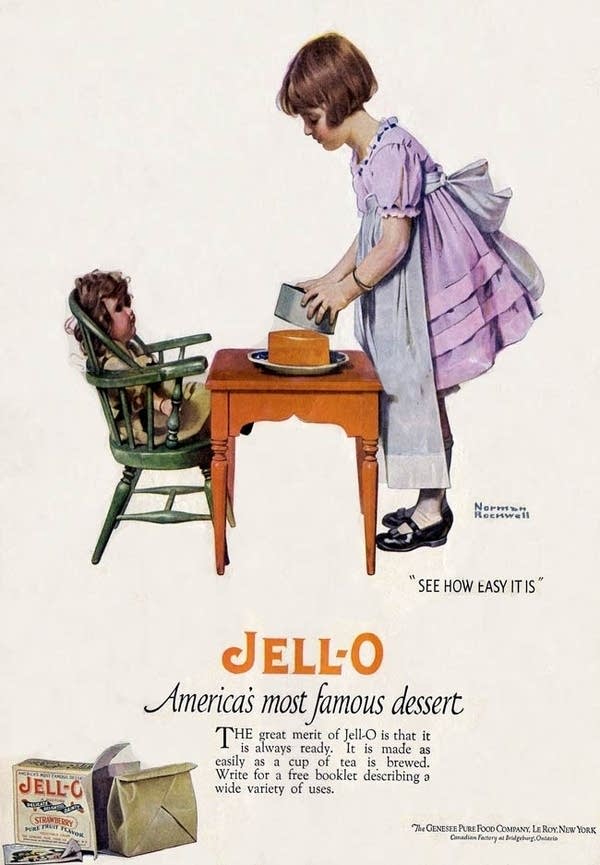

Just after the turn of the century, Jell-O’s first advertisements appeared in the Ladies’ Home Journal, said Tyler Angora, curator of the LeRoy Historical Society.

“If you look at some of the advertisements, the very early ones — which you'll tell by the lovely Edwardian-dressed ladies that grace the cover of most of them — Orator really focused his advertisements towards middle- to upper-class women,” he said.

It targeted the women who, just a few decades earlier, would likely never have dreamed of seeing such ritzy desserts in person. But with Jell-O, these consumers could be like the genteel ladies who had a full staff of servants. Jell-O helped to scratch that aspirational itch.

Then came the Jell-O explosion. In 1904, the world was introduced to Jell-O at the St. Louis World’s Fair. By 1909, the Genesee Pure Food Company posted earnings north of $1 million. Four years later, that number would double.

Advertising Jell-O to the world

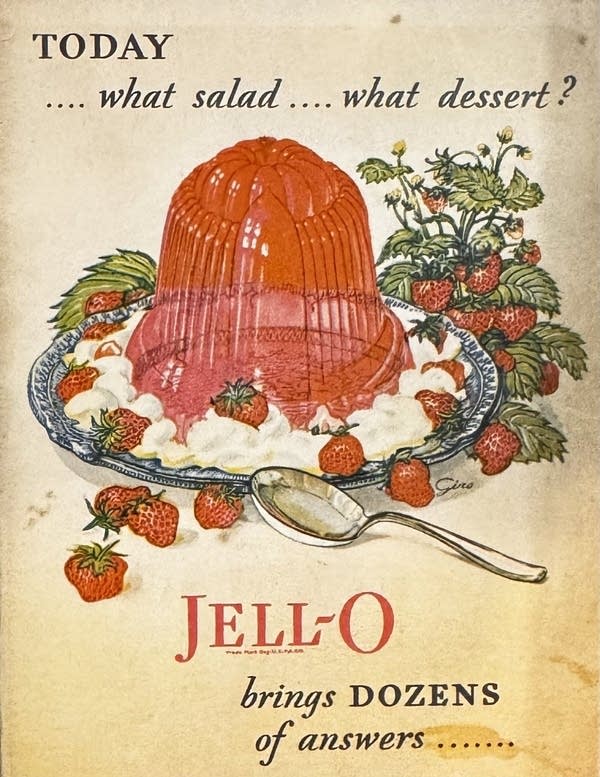

In its early days, Jell-O would often advertise itself as America’s most famous dessert. And it was a distinctly American treat.

Because Jell-O was easy to make and digest, it was served to newly arrived immigrants at Ellis Island.

The novelty was just part of it; Jell-O was eye-dazzling, too. “It's red, it's yellow, it's orange, it's all these colors that make it look as though maybe it's not food — it was far more versatile than anything resembling food had ever been,” said food historian Laura Shapiro.

The popular Jell-O Girl mascot emphasized just how easy Jell-O was to make in each advertisement. Others reiterated its accessibility, at just 10 cents per box. These things — its kid-friendly ease and flavor, which appealed to mothers, its low price — would become throughlines in Jell-O’s marketing for years to come.

Another major innovation? Recipe booklets, to help housewives understand what to make with this alien-seeming dessert, free of charge.

Jell-O’s marketing was masterful in meeting shifting consumer demands.

Recipe books printed during the Great Depression, for example, would show illustrations of people noshing in gowns and tuxes on dishes that evoked classy dinners or exotic destinations — like orange tartlets glacés, angel Charlotte Russe, or Bavarian date slices. In that way, it was an affordable form of escapism.

During World War II, sales were strong, although Jell-O production took a hit from wartime rations of sugar, and consumers reported difficulties finding Jell-O on grocery store shelves (even after the war ended).

“This sugar short-season, everybody’s favorite Jell-O and Jell-O Puddings … will be rare and festive delicacies,” reads one 1945 ad. "When the sugar shortage eases up, the makers of Jell-O and Jell-O Puddings will once more be able to make all that folks want.”

Throughout it, though, Jell-O was marketed as something economical that could help stretch money and food supplies in times of economic hardship.

Jell-O’s advertising was multimedia, too. It sponsored the popular Jack Benny Program — which would also go on to be sponsored by Grape-Nuts Flakes and Lucky Strike cigarettes — from 1934 to 1942.

And in print media, you have advertisements illustrated by artists like Rose O'Neill and Norman Rockwell.

According to Shapiro, Jell-O came of age alongside other industrialized versions of food, like instant cake mix, for example.

“It used to be that if you baked a beautiful cake, you were really special. You had put time and money into it; it could be served to the boss coming to dinner. After a while, you could do a cake that looked a lot like that out of a cake mix. It didn't cost much, took you five minutes,” she said. “So a lot of class attachments to the idea of food changed, I would say, at midcentury.”

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Jell-O reached its peak; it’s estimated that in 1968, the average American household consumed 16 packages of Jell-O each year.

It’s also around this time frame that recipes reached peak kitschiness.

The texture and flavor combinations defy the imagination: Cauliflower radish salad. Lime cabbage salad. Avocado strawberry ring. And, perhaps the most grimace-inducing, jellied bouillon with frankfurters — to be fair, it was a recipe developed by Jell-O rival Knox Gelatine — which utilized beef stock, diced celery, and hard-boiled eggs. (Some of which are allegedly making a comeback.)

After Jell-O’s peak came the fall.

Jell-O brand gelatin advertising was still geared toward women in the later decades of the 20th century. But, far from its turn-of-the-century aspirationalism, it morphed into a bona fide working-class dinner addition. And it was perfect for modern moms who, by the ‘70s and ‘80s, were increasingly juggling motherly duties with work lives.

On into the ‘80s and ‘90s, Jell-O positioned itself as a kid-friendly brand. Jell-O frozen pops and Jell-O jigglers were introduced. Bill Cosby was a Jell-O spokesperson around this time. (Remember, this was when Cosby was America’s dad). When Jell-O turned 100 in 1997, to celebrate its centennial, a sparkling grape flavor billed as “the champagne of Jell-O” was released.

At this same time, though — and on into the aughts — you have what I like to call the “fratification” of Jell-O. There’s the Jell-O shot, which gains steam on college campuses. There’s even Jell-O wrestling, where bikini-clad women tussle in kiddie pools full of Jell-O.

Over time, though, consumer behaviors changed and moved away from palates that favored Jell-O. The sale of sweetened breakfast cereals fell. After rising for decades, calorie intake shrank. Americans began opting for fresher foods, which hit the makers of packaged food products like Jell-O hard. Sure, Jell-O wasn’t particularly unhealthy — it’s low-calorie and low-fat — but it’s not particularly healthy either.

Why give kiddos fruit-flavored snacks when you could just give them, well, fruit? Or anything else that doesn’t take significant lead time to prep? And don’t even get me started on the artificial colors.

I reached out to Kraft-Heinz, the parent company of Jell-O, for comment, but they did not respond to my request. According to reporting by the Associated Press, Jell-O sales fell from $932 million in 2009 to $753 million just four years later. As for current Jell-O sales … well … when was the last time you saw Jell-O at a party?

The road ahead may still jiggle

This is not meant to be an obituary for Jell-O — not anywhere close to it.

I’ve been to at least four parties in the past year in which hosts will break out a box of artisanal “cocktail jellies” from Solid Wiggles, a boutique gelatin shop in New York. Think of a modern twist on the classic Jell-O shot.

Instead of those teeny plastic shotglasses filled with multicolored Jell-O and cheap vodka, these have flavors like Cosmo, Lychee Martini, mezcal negroni, and French 75. They’re also cubes that look more like modern paper weights than something to ingest.

It’s funny to me to see the proliferation of all things wiggly and jiggly like that as an adult in New York. The Lime Jell-O Dessert that tastes like home to me is fluffy, messy, feels like it can put the kitsch in kitchen, and costs less than $10. Artisanal, alcohol-infused gelatin cakes, though, feel more akin to the dishes that Victorian houses with staffs of a dozen or more might enjoy.

For what it’s worth, Kraft-Heinz did come out with a line of playful Thanksgiving-themed Jell-O molds this year, harkening back to some zany molds of yore.

But I think I’m good on the molds and the boozy cakes, at least for the moment. Because I’m headed back to the Midwest for the holidays, and I’ve got a few scoops of Lime Jell-O Dessert with my name on it.

Grandma Dawn’s Lime Jell-O Dessert Recipe

Ingredients:

1 package cookies and cream cookies, like Hydrox cookies or Oreos

1/4 cup butter

1 package lime Jell-O

1 can evaporated milk

Juice from one lemon

Directions

First, crush 1 package (14 oz) Hydrox chocolate cookies and mix with 1/4 cup melted butter.

Spread half of the mixture of crushed cookie mix on the bottom of the pan. (You’ll save the other half for the topping.)

Next, dissolve 1 regular package of lime Jell-O, stirring constantly for 1 minute in half a cup of hot water.

Let cool while whipping 1 can (14 oz) of chilled evaporated milk. (Whip for about 4 to 5 minutes in a glass bowl, not plastic.)

Mix 2 tablespoons freshly squeezed lemon juice into the cooled Jell-O, then add it to the whipped evaporated milk, and gently fold with a dry (not oily) rubber spatula until lime Jell-O mixture is fully disbursed.

Spread the mixture evenly over the layer of cookies, then sprinkle the remaining cookie mix over the whipped milk mixture.

Immediately refrigerate.

Enjoy!