Why trustworthy data is so important to everyone in the U.S. economy

It’s not a story about wonky statistics. It’s about America’s reliability as a borrower of trillions of dollars, something that underpins our global economy.

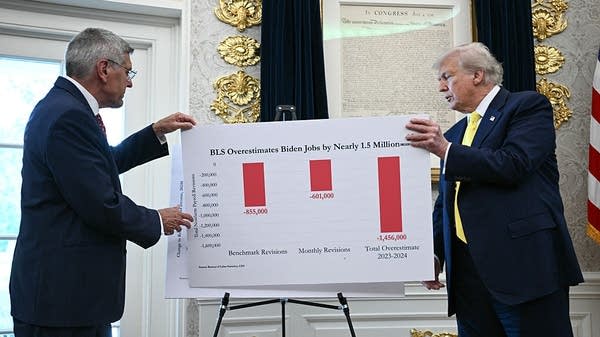

The internal watchdog for the Department of Labor has opened an investigation into how the Bureau of Labor Statistics collects data on jobs and inflation. This comes amid major downward revisions to hiring numbers for the U.S. economy: 1 million fewer jobs added than initially reported in the year through March.

There's been pressure on the BLS from the president, who fired the agency's commissioner in August. The administration has cast doubt on BLS data.

What do we make of all this?

“Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio put that question to Justin Wolfers, an economist with the University of Michigan. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Justin Wolfers: The way this story started is a little bit too revealing. The president got told some bad numbers about the economy and then insisted on firing the person who delivers those numbers. Look, when you face bad economic numbers, you've got two choices: fix the economy or attack the numbers, and he chose the latter.

The chief complaint from those who've backed up the president has been the bureau's numbers are imperfect. And they absolutely are. Because it's such a difficult task to measure how many people are in work in an economy of our size, and an economy in which 6 million people gain and lose jobs every month. That's not the right way to think about the value of statistics. The question is: Is there a way of doing it that's less imperfect? And so far, no one has come up with any approach that's less imperfect than what the Bureau of Labor Statistics is doing.

David Brancaccio: Some have drawn comparisons with, in China, they stopped reporting youth unemployment when it started looking inconvenient some years ago.

Wolfers: Yep. And in Argentina, they falsified the inflation data. And this is something that happens not in serious first-world economies that borrow trillions of dollars at very low rates in international capital markets. This comes from countries without the tradition of democracy, often driven by autocrats. Look, it's this simple: Truth is what statistics are all about. I think we're served by having more truth. I can't imagine a way in which having less truth leads to better economic policy. I can see how it leads to better political outcomes for one person.

Brancaccio: I mean, there are real consequences. This may sound arcane to some people, but it could lead to higher costs of borrowing on your credit cards if our statistics are called into question.

Wolfers: Absolutely. So that is the story of Argentina, which is, you can try and suppress statistics, but you can't suppress reality. And there's one other thing, which is, we borrow trillions of dollars in international markets. Now, of course, I'm willing to lend you money if I know that you're a really safe person to lend money to. But if you're not willing to tell me the truth about your finances, what is it I'm going to infer about you? I'm going to infer that the reality must be terrible. As a result, foreign lenders are going to lend money to the U.S. as if we are a basket-case economy. Which would be very bad outcome, if the reality is that we're actually a good, strong, vibrant economy who are able to repay our debts on time and in full.