Many of us have learned tough lessons on supply and demand over the past few years.

The COVID-19 pandemic found many Americans hoarding toilet paper, jumping into new hobbies or splashing out on counterfeit N95 masks. In the spring of 2020, you might have done all three at once. Those bad old days are a useful case study for the economic fundamentals we’re covering this week.

So let’s dive into Chapter 7 of the Core Econ textbook “Economy, Society, and Public Policy.” If you aren’t enrolled yet, sign up here to get all these lessons emailed to you!

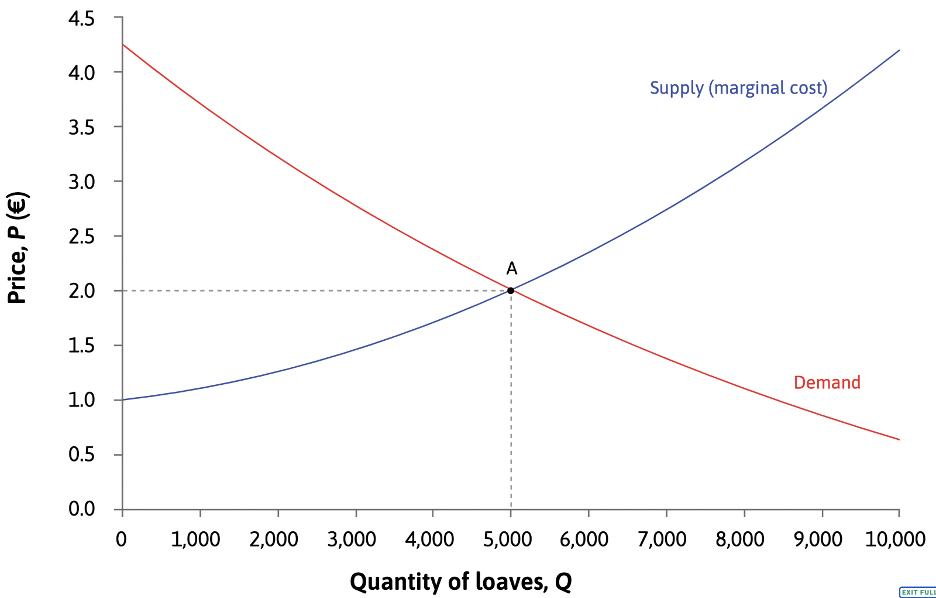

Supply and demand are competing forces governing any market you can think of — pharmaceuticals, personal training, sourdough starter — we can model them in a chart like the one below.

Here’s an example about bread from the textbook:

With the inventory on the x-axis and price on the y-axis, the demand curve slopes down and to the right. When the price of a loaf of bread goes above 4.25 euros, no one wants it. he cheaper a loaf gets, the more customers are willing to buy.

The supply curve moves the opposite way and shows the cost associated with producing more loaves of bread. It starts with the lowest price any seller would accept and slopes upward as higher prices incentivize more sellers to enter the market. The point where supply and demand meet is the equilibrium price, point A in the chart above.

At 2 euros, both the buyers and sellers of bread have achieved the “maximum surplus” from the exchange. At a higher price, you’ll have excess loaves for the day-old bin. At a lower price, the bakery will sell out before everyone who’s willing to pay 2 euros gets their loaf.

But market conditions can change, sometimes quickly. The COVID-19 outbreak upended cost and profit calculations in all kinds of industries. Manufacturing shutdowns in China restricted the supply of medical masks and semiconductors, while the prospect of quarantining drove new demand for household essentials and home exercise equipment.

These shocks threw prices into disequilibrium, and the market had to adjust. As the world opened back up, market conditions kept changing. Take Peloton: The high-end stationary bike was so popular circa 2020, the company started building a new factory to churn them out. Two years later, the company was in financial trouble and $1,500-plus bikes could be found secondhand for a steal.

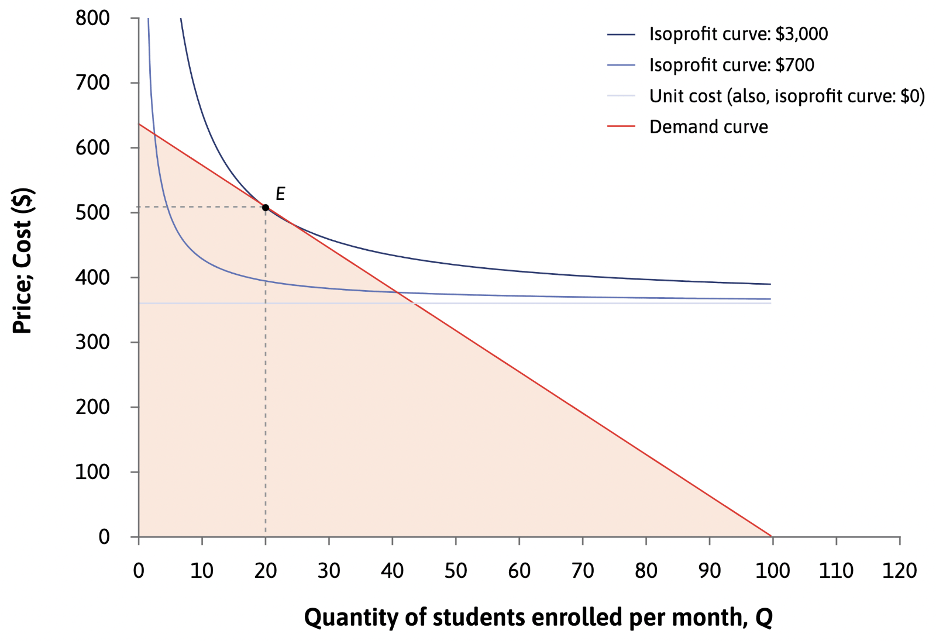

But how do firms like Peloton, or your local bakery, set prices? They start with the cost of making their product or providing their service. Raw materials, equipment, labor, even opportunity costs go into that calculation. Firms then use those numbers to determine how to maximize profits, producing exactly the quantity they expect to sell. Here’s what that looks like when plotted on a graph in the form of isoprofit curves:

Zero profit occurs when the marginal cost of making one more unit of something equals the price the product is sold at. Businesses typically try to set prices higher than that in order to make a profit. So an isoprofit curve shows all the combinations of price and production that would generate a certain amount of profit.

The highest possible isoprofit curve will meet the demand curve at a sweet spot of pricing and output. The example above, about Spanish lessons, is from the book.

We’ve seen the way market conditions can change that calculation, but firms can influence the market too. Advertising and innovation can drive demand or bring costs down; just look at breakfast cereals and AirPods.

It’s important to note that even when a market is in equilibrium — and that’s rare —, it doesn’t mean the market is Pareto efficient, something we covered in Chapter 3 of the Core Econ textbook. Maximizing profits inherently comes with deadweight loss — firms will lose customers who would pay more than the unit cost, but not the price that’s offered. Firms may try to minimize that loss by offering customers different prices via discounts or dynamic pricing or control market conditions in other sneaky ways.

Finally, it’s important to remember that nothing we talked about today — maximum profits, controlled costs, pricing equilibrium — is necessarily fair.

Equilibrium price: The price where supply and demand meet, maximizing the exchange’s surplus and clearing the market.

Marginal cost: The cost of producing one additional unit of a good or service. Large firms may use economies of scale to lower their marginal costs.

Elasticity of demand: The amount that demand for a product or service changes as the price increases by 1%. Low elasticity means a flatter demand curve, high elasticity means a steeper one.

Shocks: An external change that would fundamentally alter the models we’re looking at.

Treating people differently based on categories such as race or gender is discrimination — a word I associate with a social ill, one not to be tolerated.

Tell that to the economists who framed the idea of price discrimination, a strategy in which sellers offer the same product at different prices to different buyers or groups of buyers. Retailers also refer to this strategy as “dynamic pricing.”

Price discrimination can be illegal. But what about selling discounted movie tickets to seniors or charging students less for admission to a museum? I’m not opposed to it.

At the start of the pandemic, some retailers were accused of jacking up prices for hand sanitizer. We call that price gouging. The practice violates what economists call a social preference, namely, that we don’t tolerate people trying to take advantage of one another during dangerous times.

It’s not the only sneaky way to influence the market. The textbook referenced a cartel (a group of firms that collude to increase their profits) of lightbulb manufacturers that conspired in the 1920s. Philips, Osram and General Electric agreed on a strategy of “planned obsolescence” to shorten the lifetime of their bulbs so consumers would have to replace them more frequently. The cartel named itself after the Greek god of light, Phoebus.

I’m among those who learned a lot about how the world works from Mad magazine. Mad had an occasional feature about precisely this, planned obsolescence. There were diagrams of goofy prototypes such as — to return to one of the most popular topics of the day — toilet paper with fake perforations so that clumsy long ribbons of the stuff would come spindling off, forcing you to go through the roll more quickly.

“The term ‘willingness to pay’ … sound[s] like we’re all starting with the same amount of money,” Homa Zarghamee, an economics professor at Barnard College who advises Core Econ, told David Brancaccio in 2020. “That gets very distorted when you have inequality because, really, what willingness to pay is, is your willingness and ability to pay. And so somebody with much higher income will always be willing to pay more because they’re able to pay more.”

In Chapter 8, we’ll learn about supply and demand and the “magic of the markets.”

Econ 101 is a production of Marketplace, a listener-supported public journalism outlet. Consider making a donation to support our mission to make people smarter about the economy, tech and the world. Your donation today makes for a better Marketplace tomorrow.

This course was written and edited by Ellen Rolfes, Erica Phillips, Tony Wagner and David Brancaccio. It was originally published in February 2023 and updated in November 2024.

Revisit previous lessons:

Chapter 1: The relationship between capitalism and income inequality

Chapter 2: Game theory and rational decision making

Chapter 3: How policymakers and economists assess fairness and efficiency

Chapter 4: Finding balance between work and leisure (like an economist)

Chapter 5: What is an “economic rent” and how does it influence working conditions?

Chapter 6: Why companies often pay workers more than minimum wage