“Amateur” mistakes sink thieves of U.S. technology working for China

“Amateur” mistakes sink thieves of U.S. technology working for China

Quitting to join a competitor and lying about it. Googling “clear computer data” to hide one’s digital tracks. Stuffing devices with stolen data into a locker during a police raid. Not exactly the hallmarks of professional corporate spies.

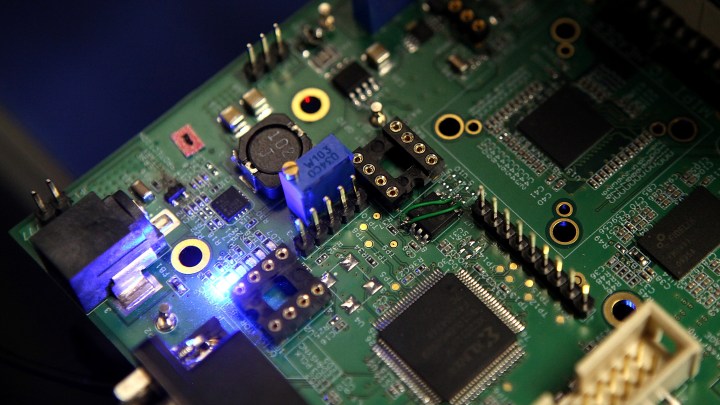

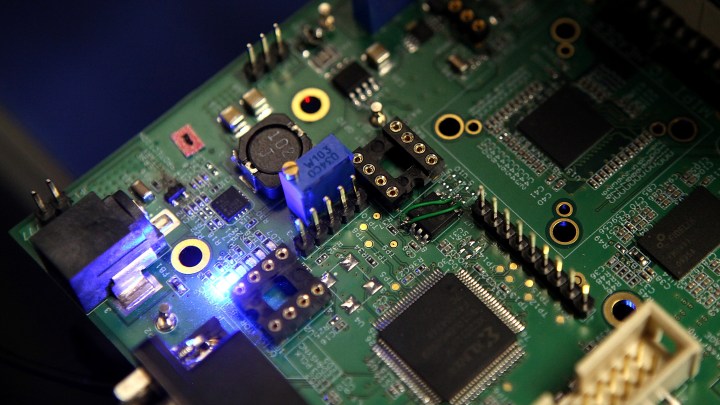

A bungled theft of U.S. semiconductor secrets lies at the center of a Justice Department case against defendants linked to a state-owned Chinese chipmaker seeking production know-how. The rookie mistakes, analysts say, amount to a case study in what not to do in the high-stakes world of economic espionage.

In the complex case, American investigators in October secured a guilty plea from United Microelectronics Corp. (UMC), a Taiwan-based semiconductor manufacturer, for “possessing and receiving a trade secret belonging to Micron Technology,” an Idaho-based American chipmaker. The U.S. government case, and a separate suit filed by Micron, accuse UMC and three employees of planning to pass Micron’s proprietary methods to China-based Fujian Jinhua Integrated Circuit Co.

As part of its plea, UMC agreed to pay a $60 million fine and cooperate with the ongoing Justice Department investigation.

“UMC takes full responsibility for the actions of its employees, and we are pleased to have reached an appropriate resolution regarding this matter,” Stan Hung, UMC Chairman, said Oct. 29 in a company statement. A UMC spokesperson said the company had no further comment.

Micron stated it will continue to seek “full restitution” from UMC in a separate civil case, Bloomberg reported on Oct. 28.

“UMC’s guilty plea points this case towards trial against Fujian Jinhua in 2021,” U.S. Attorney David L. Anderson said in an Oct. 28 press release.

“Behavior to steal another firm’s technology does not exist,” Fujian Jinhua stated in a Nov. 3, 2018 release. The company pleaded not guilty in court in 2019. Fujian Jinhua had no further public comment, a company representative said.

Micron did not immediately respond to requests for additional comment on Dec. 24.

This case stands at the center of the Trump administration’s “China Initiative,” a series of investigations designed to counter what the department calls “Chinese national security threats.”

“How did the guy who stole the IP have the chutzpah to do that?”

Jim Handy, semiconductor analyst

This tale begins with three engineers working for the American chipmaker Micron, based in Idaho. One of them, Kenny Wang, is accused of stealing some 900 of Micron’s intellectual property files back in 2016.

“First thing I wondered was, how did the guy who stole the IP have the chutzpah to do that?” said Jim Handy, semiconductor analyst and president of the research firm Objective Analysis. Handy also represents Fujian Jinhua under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, federal filings show.

“When you work for a company like that — cuz I’ve worked for Silicon Valley companies my entire career — one of the first things they make you do is sign something that says, ‘Anything I develop while I’m here belongs to the company.’ “

According to the indictment, Wang took Micron’s end-to-end recipe for making memory chips known as DRAMs — semiconductors embedded in our phones, computers and other devices. The entire DRAM blueprints can fit on a tiny digital memory card, Handy said.

“A lot of people talk about it as being the size of your thumbnail,” Handy said. “And it would be like that if you flattened your thumbnail out. But it sounds painful.”

When Wang quit Micron, he committed one of several alleged mistakes cited in the criminal and civil cases against him and his partners.

Mistake #1: Lying about why you’re quitting

Court documents say that Wang — DRAM information in hand — announced plans to leave Micron “to go to his hometown and join the family business.” In fact, he joined a Micron competitor, Taiwanese chipmaker UMC, in April 2016.

But not before making two additional mistakes:

Mistake #2: Using a work laptop to steal stuff

Wang “downloaded Trade Secrets … from his Micron company laptop,” the indictment states.

He’s also accused of uploading the proprietary data to his Google Cloud account.

Mistake #3: Trying to erase tracks by Googling

Then, in an apparent attempt to hide his digital tracks, Wang Googled the phrase “clear computer data,” the indictment states, and ran a piece of software called “CCleaner” to wipe his laptop.

“The fact that he downloaded the advice about how to clear off his disk, that added to the indications that he was guilty,” Handy said.

But before authorities caught on, Wang delivered the secrets to UMC, which had signed a semiconductor manufacturing partnership with Fujian Jinhua in China.

Upon joining UMC, Wang joined two other ex-Micron employees — and now co-defendants in the Justice Department case — at the company.

Wang is a chipmaking professional who held the title process integration manager at Micron. This expertise is critical to the complex process of turning blueprints into physical products.

“Technological knowledge is as important as the actual widgets,” said Anna Puglisi, a former counterintelligence officer for the U.S. government and now a fellow at the Center for Security and Emerging Technology at Georgetown University. “That’s what we’re talking about. It’s the art of making something. It’s the know-how that makes it so much more challenging.”

Mistake #4: Using competitors’ supersecret code names in public

So Wang and UMC had what they needed to make chips. Instead, they made … their next mistakes.

Court documents say UMC and Fujian Jinhua managers went recruiting in Silicon Valley in October 2016, throwing around Micron’s proprietary company vocabulary, including internal code names that outsiders would not normally know. Giveaway.

Mistake #5: Shoving evidence into a company locker

Four months later, when authorities in Taiwan raided UMC offices in February 2017, Wang and his collaborators shoved the incriminating evidence into a locker, the DOJ indictment states.

The devices were found.

“They were just corporate actors acting like corporate people, which is to flush everything down the toilet and hope for the best during a raid,” said Matthew Brazil, a fellow at the Jamestown Foundation research organization and contributing writer to the online publication SpyTalk. “This is an amateur effort.”

Brazil, co-author of the book Chinese Communist Espionage: An Intelligence Primer, said many cases of attempted economic espionage turn up these types of errors. For instance:

“Packing evidence into their suitcase before they go to China, instead of maybe FedEx it, which would have been a lot better,” Brazil said. “Or destroying evidence in one way, [but] leaving it intact in another.”

Mistake #6: Handing an incriminating phone to an aide, then lying about why

During the raid on UMC, Wang handed his phone containing incriminating evidence to a company assistant who left the facility. “When confronted with the fact that the criminal authorities knew about his missing cellphone, Wang lied and said that the assistant borrowed his phone that morning ‘because she wanted to see some photos,’ ” according to Micron’s civil complaint against UMC.

With Taiwan authorities’ help, the U.S. government in 2018 indicted UMC, Kenny Wang and two colleagues, as well as Fujian Jinhua.

“These five defendants have been charged with conspiracy to commit theft of trade secrets, economic espionage, and the conspiracy to commit economic espionage,” U.S. Attorney Alex Tse said at the time.

The alleged theft was meant to benefit Beijing, the indictment states. The Chinese government has established a $29 billion fund for chipmaking development, making clear to local governments that semiconductor manufacturing is a top-level nationwide priority. These measures are a hallmark of Chinese industrial policy.

“Whether it’s been shipbuilding, steel, aluminum, solar, LEDs, when the central government sends a signal out to the provinces, to the cities, “Thou shalt develop this industry,” we see this massive wave of investment by local municipalities across China,” said Jimmy Goodrich, vice president of global policy for the Semiconductor Industry Association. “Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.”

China is seeking to reduce its dependence on imported microchips, especially those used in weapons or surveillance, said Scott Kennedy, China economic policy scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“Chips power our national security and internal security,” Kennedy said. “And [Chinese leaders] may simply believe that chips have back doors or other ways in which the West can maintain their dominance over China.”

But the Chinese company in this story, Fujian Jinhua, has not succeeded for China. After being indicted and then hit with U.S. sanctions, it hasn’t sold a single memory chip, analyst Jim Handy said.

But Fujian Jinhua may not be the only Chinese semiconductor firm trying to lift American secrets, through business partners or otherwise.

“Like in corruption, you only hear about the corruption that gets found out,” Kennedy said. “There are probably lots of other cases where folks have succeeded that we don’t know about.”

Correction (Dec. 23, 2020): The original audio and web version of this story misstated where Micron is based.

Update (Dec. 24, 2020): The text includes statements from the Department of Justice, Micron, UMC and Fujian Jinhua; and identifies Jim Handy’s representation of Fujian Jinhua.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.