Vox’s Dylan Matthews explains where comparisons of developing artificial intelligence and nuclear weapons work and where they fail.

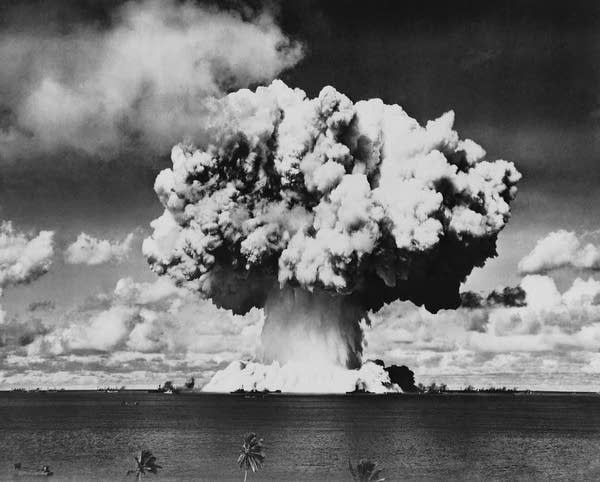

The movie “Oppenheimer,” about the making of the nuclear bomb, opened last week, and the subject matter has spurred an unavoidable comparison with artificial intelligence.

Leaders at AI companies like OpenAI and Anthropic have explicitly framed the risks of developing AI in those terms, while historical accounts of the Manhattan Project have become required reading among some researchers. That’s according to Vox senior correspondent Dylan Matthews.

Marketplace’s Meghan McCarty Carino spoke to Matthews about his recent reporting on the parallels between AI and nuclear weapons.

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Dylan Matthews: The main similarity, which might not be obvious, is the potential for harm. I think now when we look back at nuclear weapons, we see a wholly negative thing. But at the time, nuclear fission, and its potential in terms of nuclear power, was really new and hadn’t been done before. So, nuclear looked like a double-edged sword that could give and take.

Similarly, I think AI has a lot of promise, but at the same time, we’re creating a new intelligence system that we don’t really understand. We don’t know why it does the things it does. We basically just feed it data. So, I think there’s both a broad fear of what happens when you have a really intelligent system that we don’t fully know how to control and a lot of more specific worries about what bad actors might be able to do with a system like that.

Meghan McCarty Carino: What are some of the important differences between these two fields?

Matthews: I think the most important difference is that AI is what economists would call a general-purpose technology while nuclear fission is a pretty specialized technology. Nuclear changes the way we get energy, but it doesn’t change a whole lot else. AI seems more like electricity, or the telephone, or the internet, where everything around it changes as that technology emerges. Nuclear really was not like that. I think in some ways, that makes AI harder to regulate, because the more useful it is, the less likely we’re going to want to tamp down on it.

McCarty Carino: Overall, do you think this is an apt comparison?

Matthews: I think it’s a useful comparison for conveying just how fast things are moving and the sense of urgency in both fields. Part of what’s interesting about nuclear weapons is a lot of scientific progress happens very gradually, over decades. We’ve recently had some breakthroughs in nuclear fission, for instance, and that’s taken since the 1950s to get off the ground.

The first experiments showing that you could split a nucleus happened in late 1938, and less than seven years later, we had nuclear weapons and two cities had been destroyed using them. That’s just an astonishing pace of scientific progress, and it required a huge investment and a huge amount of manpower to get there.

I think what alarms people about AI is that it seems like things are proceeding really quickly, indeed, almost exponentially. You might not be worried about what ChatGPT can do now, but there’s reason to think that it’s going to be twice as good in a year or 18 months, and it will be twice as good as that a year to 18 months after that. So, I think there’s a similar mindset and emotional understanding of it as something that’s moving really fast that we are going to struggle to get a handle on.

McCarty Carino: Another similarity seems to be the paradoxical sense of concern about what this technology means for humanity by the very people who are working to advance it. Does that seem kind of similar to what we saw with the Manhattan Project?

Matthews: Yes, I think in some ways that is the most important parallel. I think a lot of the people at AI companies like OpenAI and Anthropic in particular were motivated by the idea that this could be a very dangerous technology, and that’s why they wanted to study it.

That’s a somewhat different motivation from that behind the Manhattan Project, but I think there was a lot of melancholy and self-doubt after the bomb was actually created and used not against Nazi Germany, but against Imperial Japan. In AI, there’s a similar set of mixed feelings about what’s going on. What’s interesting is that in AI, they’re happening all at once, whereas in the case of nuclear weapons, it happened kind of sequentially. The people building these systems today are simultaneously filled with trepidation about it.

McCarty Carino: When we see leaders in this field, like Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, and other leading technologists coming out with statements about how AI poses a risk of extinction similar to nuclear weapons, this comparison would seem to cast AI in a negative light, by comparing it to something that killed hundreds of thousands of people. But is there any way in which these kinds of comparisons actually serve the AI industry?

Matthews: I’ve heard this argument from a few people that say these statements are a form of marketing for AI companies. One person I spoke to likened it to saying, “Look at my hot rod! It goes so fast! You wouldn’t want to be in such a fast and dangerous hot rod, would you?” But I think the more serious answer is that when you talk to people like Ilya Sutskever, the chief scientist at OpenAI, or Dario Amodei, CEO and co-founder of Anthropic, or Rohin Shah, research scientist at DeepMind, these are people who got into this work in part out of concern about what these systems could do and had been writing for years about the dangers of a rogue, uncontrollable AI. Maybe they’re playing a very long con where ever since they were undergrads, they were talking about how AI would be really dangerous so that they could later promote a company they work for, but I find that a little far-fetched.

I think they sincerely believe these systems are very dangerous. Could they be wrong? Sure. We’re in the very early stages, and at this point, we mostly have theory without a lot of evidence about what super advanced AI systems could look like. So, I’m totally open to the idea that they’re just mistaken, but I find it a little harder to believe that they’re just insincere.

McCarty Carino: What lessons does the development of nuclear weapons in the 1940s teach us about AI development today?

Matthews: I think one lesson is the need for what Oppenheimer called candor or what his mentor, Niels Bohr, would call “open science.” As soon as it became clear that the United States was going to have a nuclear weapon, Bohr started going to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill and begging them to share as much as they could with Joseph Stalin. He believed that the more people knew about this technology, the less likely it was to develop into a harmful arms race caused by mutual mistrust and fear, and that open and clear communication about what was happening was the best way to ensure safety.

The parallel for AI is not necessarily to make everything open source and put it on the internet with no guardrails. Oppenheimer and Bohr were not saying we should print a “how to make a nuclear bomb” guide in the newspaper. But there’s a risk of similar arms race dynamics, and those dynamics are exacerbated by mistrust, and in particular mistrust between the allies of the U.S. and Europe, and China. A way to prevent that might be committing to more open sharing of who is buying what processors, who is training what kinds of models, and ensuring the processors have auditing capability to make sure that countries can check on each other and that they’re not developing dangerous models.

I think there’s still a lot of promise in that broad approach for ensuring mutual safety and ensuring the kind of trust you need for international agreements that might be able to contain the worst possibilities of this technology.

The parallels between AI and nuclear weapons get a bit spooky. In an interview with The New York Times, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman revealed he shares a birthday with Robert Oppenheimer. In that same interview he also compared his company to the Manhattan Project, saying the U.S. effort to build an atomic bomb during the World War II was a “project on the scale of OpenAI — the level of ambition we aspire to.”

That historical account of the Manhattan Project I mentioned that so many people in the AI world are reading is “The Making of the Atomic Bomb” by Richard Rhodes.

In our conversation, Dylan Matthews mentioned visiting the offices of the AI company Anthropic on a reporting trip and seeing a copy of the tome on a coffee table as well as an Anthropic employee with an Oppenheimer sticker on his laptop.

The Atlantic recently interviewed Rhodes about the popularity and resonance of his book more than 35 years after he wrote it. And I have to admit, it’s on my bedside table too. When I started the book, I was struck by a quote from Robert Oppenheimer in the opening pages: “It is a profound and necessary truth that the deep things in science are not found because they are useful; they are found because it was possible to find them.”