It’s easy to create a fake account on social media. Facebook has found that billions of accounts on its platforms could be fake. Last year alone, Twitter suspended more than 70 million bots and fake accounts, but they keep appearing. The more bots there are, the more they can manipulate the online conversation.

Host Molly Wood spoke with Filippo Menczer, a professor of informatics and computer science at Indiana University. He studied the effect of Twitter bots specifically in spreading misinformation around elections. Wood asked him: How much are bots changing our conversations? The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Filippo Menczer: It’s hard to prove that causal chain of events. We do know, however, that bots can be used effectively to manipulate what information we’re exposed to online. And that can also threaten journalists, because if they think that this is what people are talking about, then they can cover it. And that generates a second wave of attention.

Molly Wood: Why is it so hard to solve this problem, to even detect these bots, let alone get rid of them?

Menczer: It is a very difficult problem. First, platforms are inundated with this kind of abuse. So even if you have a good machine-learning algorithm that attacks the great majority of them, even missing just a few, that will still have many millions of potentially fake accounts. But it is also hard to detect them because there are many kinds of bots, and many of them use humans to generate the content so that you cannot easily spot patterns of bots. And then finally, the platforms can pay a huge price for suspending an account, because even if it was used for abuse, it is hard to prove. The person who was using those bots can then say, “Look, I’m a human. I posted these things myself.” It is very difficult to prove otherwise.

Wood: How many followers does a bot need before it can have a significant impact on our online conversations?

Menczer: We’ve tried to explore that question by building a model that simulates a social media network. In this simulated system, we can play with the world and ask “what if” questions. One of the metrics that we can use in this simulated system is what you described, that is, how many humans follow these bots. What we find, not surprisingly, is that the more bots you have, the more quality of the information in the system goes down. If there are enough of them — if bots have enough users — you can basically control the platform. So if I want to target a community — for example, people who are vulnerable to conspiracy theories — then I can create a bunch of bots that just retweet and mention people in this community and they follow them, and then they get followed. And after a while, they can become integral part of that community. And at that point, they can basically control it.

Wood: There’s a law in California and a discussion about federal efforts to force bots to identify themselves when they’re interacting with people, especially around political messaging. What are the complications around that solution?

Menczer: I believe that that seems like a very reasonable thing. But there are those who argue that this is an infringement on the First Amendment — bots somehow have free speech rights. The idea is that there is somebody behind those bots, and those people should not be limited in what they say. On the other hand, there are opinions, including mine, that say that if you don’t impose any limits on that kind of speech, then you’re allowing people to suppress other people’s speech, because I can create thousands of fake accounts. And just by flooding the network with junk, I can keep other people who are real humans from being heard.

Wood: It’s clear that this is a difficult problem to solve both technologically and politically. But do you feel like these big social media platforms — Twitter and Facebook — have done enough?

Menczer: Certainly, they were very late to act and to realize the identity of the problems and how much their platforms could be abused. But they are aggressively taking down accounts, although perhaps not aggressively enough. But then in the end, there is also risks of being too aggressive, because they’re often labeled as politically bias. So even if they build better machine-learning algorithms to detect the abuse, then attackers can develop better bots that are harder to detect.

Wood: What are some of the tools that your lab has created or some of the tools that people or journalists or political candidates could be using now?

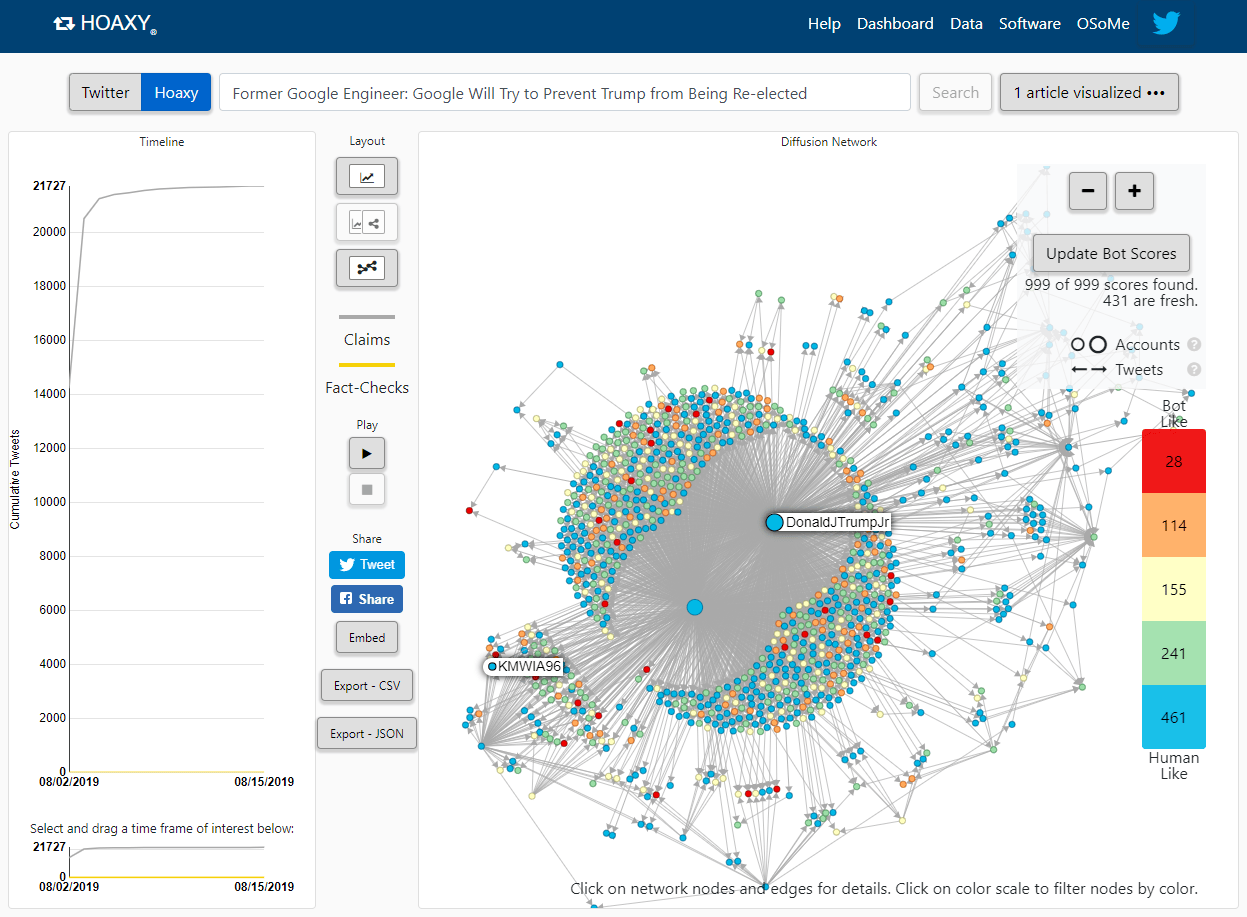

Menczer: We are developing tools to try to detect automated accounts. We have one called Botometer, which is a machine-learning algorithm that uses a very large number of features to try to recognize accounts that have behaviors that are like those of known bots and automated accounts. Another tool that we have is called Hoaxy. Its purpose is to help people visualize how information and misinformation spread online. For example, if you want to see who’s talking about something on Twitter, you can visualize the network of who retweets whom, who mentions whom, who are the most influential users, what are the different communities. They’re talking about different aspects of an issue. This tool is also connected with Botometer so that you can also look at whether bots are being used to promote a narrative or meme or link to an article or whatever.

So those two tools can be useful in detecting abuse. And we have another one that right now [is] still in alpha testing, but we hope to release a public beta version soon, maybe this month or next month, which is called Bots Slayer. It makes it possible for any journalist — or even citizen or researchers or even people working for campaigns — to set up their own system to monitor what is being said about a certain topic that they’re interested in. And to see when there is a group of accounts that are suspicious because perhaps they use automation or they’re coordinating to try to push a certain narrative. People can more easily study what is happening online and try to understand whether there is a coordinated disinformation campaign that is trying to push a message.

Wood: Based on your research, how concerned are you about the influence of bots and automated accounts on social media during the 2020 election cycle?

Menczer: We’re concerned because we are seeing, even right now with some of the tools that we develop in our lab and certainly on social media, that there are fake accounts that are used as part of disinformation campaigns, and we assume that this is only going to increase as the elections approach. We’ve noticed a lot of this activity in 2016, and we noticed bots played a crucial role in amplifying the spread of misinformation in 2016. Given those trends, there is no reason to think that this is going to get any better anytime soon.

If you would like to get a little more bummed out about the sad state of affairs on Twitter and social media, here’s the link to Menczer’s research. It’s fascinating to play with the Botometer tool that his team created.

There’s a Politico piece from November on whether bots have First Amendment rights. California, of course, is about to enact a new law that would force bots to identify themselves if they’re trying to sell you something or spread political speech. But, as you heard Menczer say, that might not be a slam dunk because recent Supreme Court rulings seem to lean in favor of the bots.

The good news is that journalists are starting to realize how much conversation online that seems real might just be bots trying to fan the flames and make a topic seem bigger than it is.

Earlier this month, the Wall Street Journal partnered with a social media analytics company to look at Twitter activity and trending topics after the Democratic debates in June and July. It found that bots appeared to amplify racial division, specifically. One instance of this is #DemDebatesSoWhite, and conspiracy claims about the racial heritage of Sen. Kamala Harris, which were later retweeted by prominent activists, and at one point, Donald Trump Jr.

Don’t believe everything you read on the internet. With an update for the bot era, if it seems like a tweet was designed to make you mad, it certainly was.