What determines the effort you put in at work? It probably has something to do with what you get paid.

So answer this question for yourself: If I were paid $5,000 more per year, how much harder would I be willing to work? But what if it was $10,000 more? Would your answer change? Economists and employers are also thinking about this question and using mathematical models to set the wages they offer.

Welcome to the sixth week of Econ 101. Chapter 6 of the Core Econ textbook “Economy, Society, and Public Policy” explores the role that for-profit companies play in a capitalist economy.

If you aren’t enrolled yet, sign up here to get all these lessons emailed to you!

One of the key components of a capitalist economy are companies or firms, which are businesses that:

Hire people as workers and pay them wages in exchange for their labor

Buy inputs to produce and market goods and services

Aim to make a profit

Despite their very different views on capitalism, conservative University of Chicago economist Ronald Coase and “The Communist Manifesto” author Karl Marx arrived at a similar understanding of the authoritarian power structure within firms. Unlike markets, where buyers and sellers voluntarily and freely engage in trade, firms have more power to dictate what workers do on the job.

Economists describe the relationship between managers and workers in simple terms: Bosses give orders to employees and decide whether to promote or fire them based on the amount of effort they put into their work. Employees’ effort is an important metric for determining how much profit firms can make. It’s also expensive and difficult for macroeconomists to quantify. In the real world, it often seems subjective who gets fired and who gets promoted.

Management and workers both expect to benefit from entering a labor contract. But the relationship can get tense because company owners often want to pay less and get more out of their employees. Workers, on the other hand, want higher wages for less effort.

The employer’s goal isn’t to get every employee to love their work, but to like it enough that they will do a good job and stay with the firm. That’s why employers often offer higher wages — not out of generosity, but to motivate the employee. A disgruntled employee is less likely to quit when wages are higher and the costs of losing their job are higher.

Sometimes employers will let workers go if they think they can find new workers who will be more productive. Even the threat of this can push existing employees to put in more effort. This is especially true during recessions, when unemployment rates go up, along with the cost of losing one’s job. Economist Edward Lazear found evidence of this when observing increases in worker productivity at one large company during the financial crisis of 2008. He and his co-authors found that the higher productivity was due more to increased effort by existing workers than the result of hiring new workers with stronger skill sets.

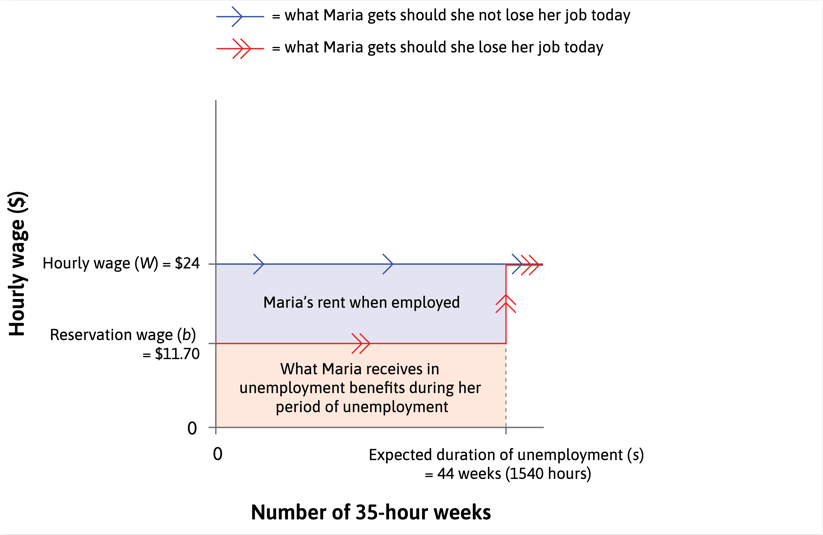

We can calculate the cost of a job loss by subtracting what an employee would make if they lost their job, including nonwage benefits and the costs of starting a new job, from what they’d make if they stayed employed. Economists call this figure employment rent.

Take the hypothetical example of a worker named Maria who makes $24 per hour, a total of $36,960, if she worked 35 hours a week for 44 weeks. If she lost her job and spent those same weeks unemployed, she’d only make $18,018 from unemployment benefits for the same time period.

Her economic rent, the benefit she receives from keeping her job, is the difference of those two numbers: $18,942.

The more money someone makes, the greater their economic rent.

If Maria’s wages were $48 per hour, her economic rent would total $55,902, almost triple what it was at $24 per hour.

But employment rent can change even when wages remain flat. During a recession, you might expect to be out of work for a longer time, which would drive employment rent up. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government offered an additional $600 a week on top of state unemployment benefits, driving employment rent down.

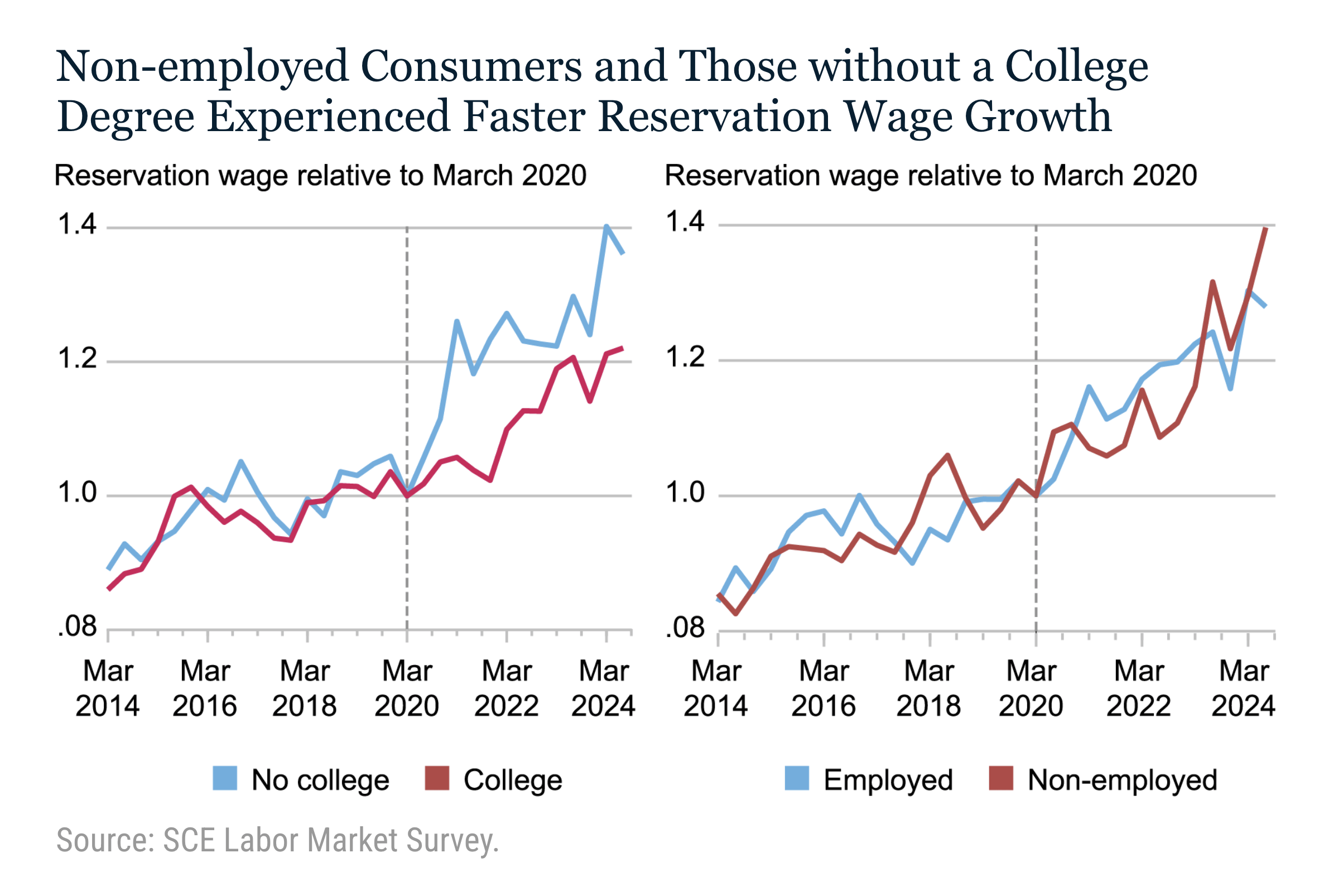

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York surveys people about their expectations for reservation wages, the minimum salary they would accept to change jobs. The average was $81,147 in July 2024.

However, as the chart below shows, the salary people expect can vary based on educational attainment or employment status. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, wage expectations for people who had not attended college and people who were unemployed grew faster than the expectations of people who had a job and those with a college degree.

Were an employer to offer a wage equal to the reservation wage, the worker would have little incentive to put in greater effort. But offering the highest possible wage may not be ideal either because there are limits to how much effort a worker can exert. As workers approach peak effort, employers experience diminishing marginal returns. In other words, employers get less bang for their buck.

Reservation wage: the lowest wage a person is willing to change jobs for or accept for a new job

Employment rent: the cost of a job loss, or the excess value between the benefit an employee receives from their job and their next-best alternative

Labor discipline model: an economic model or scenario that explains how employers set wages so that employees receive employment rent, which provides workers an incentive to work hard to avoid job termination

The chapter reminds us of an ugly truth: From a company’s point of view, unemployment is a good thing. When the jobless rate is high, the reservation wage falls. Paychecks also tend to fall, with more unemployed people willing to accept less to take a job. The United States has been close in recent years to what economists call full employment, and employers have had to pay more to recruit people.

Want to learn more about the dynamics between employees and employers? Check out these Marketplace stories to see how the principles in Chapter 6 play out in the real world.

In Chapter 7, we’ll learn about supply and demand and the “magic of the markets.”

Econ 101 is a production of Marketplace, a listener-supported public journalism outlet. Consider making a donation to support our mission to make people smarter about the economy, tech and the world. Your donation today makes for a better Marketplace tomorrow.

This course was written and edited by Ellen Rolfes, Erica Phillips, Tony Wagner and David Brancaccio. It was originally published in February 2023 and updated in November 2024.

Revisit previous lessons:

Chapter 1: The relationship between capitalism and income inequality

Chapter 2: Game theory and rational decision making

Chapter 3: How policymakers and economists assess fairness and efficiency

Chapter 4: Finding balance between work and leisure (like an economist)

Chapter 5: What is an “economic rent” and how does it influence working conditions?