The philosopher Marshall McLuhan said, “the medium is the message.” But economists say, “the price is the message.”

The penultimate chapter of our Econ 101 textbook is all about market failures, and the ways market participants or the government can shift costs and maintain a successful market.

If you aren’t enrolled yet, sign up here to get all these lessons emailed to you!

This chapter starts by explaining the “magic of the market,” a way to look at the stuff around you a little differently.

Take the oil market, for example. Uncertainty gripped the world when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. Energy embargoes threatened to make crude oil more scarce, so prices rose to account for lower supply. Refiners then passed their higher costs to consumers, pushing the average gas price in the U.S. above $4 a gallon. That pain at the pump may have made someone consider alternatives like public transit. Maybe they’d be more tempted to buy an electric car, even if they didn’t follow the news or understand why prices rose.

In this way, markets convey important economic information through prices. When they’re working well, all participants are motivated to adjust their behavior in ways that make themselves better off. The textbook cites economist Friedrich Hayek, who compared the market to a supercomputer that takes in information and sets prices: “The remarkable thing about this massive computational device is that it’s not really a machine at all. Nobody designed it, and nobody is at the controls.”

Kind of a trip! We also learned this week that when markets fail to provide benefits to key players, governments step in with public policy solutions or, in some cases, buyers and sellers will negotiate a private bargain.

Think about the pollution that the combustion engine in your car emits, for example. Beyond the price at the pump, you won’t pay for the effect your carbon emissions have on society. There are lots of ways markets lead to inefficient outcomes that leave some people worse off than they could be. But how do we fix these failed markets? First, we have to get a handle on those costs.

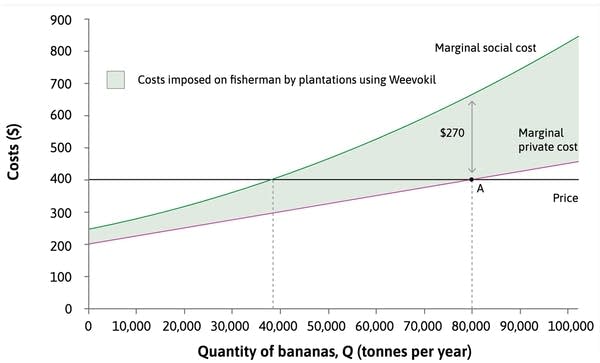

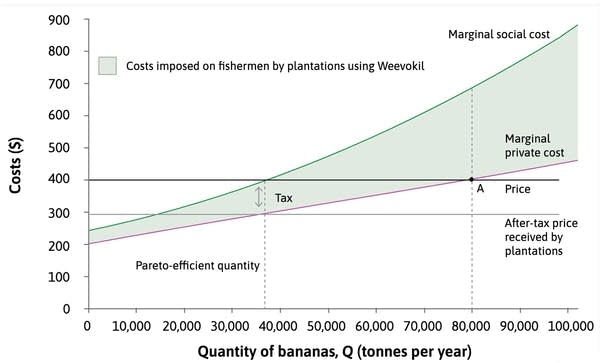

👆 This example from the book is focused on fishermen downstream from a banana plantation. The plantation uses a pesticide which pollutes the river every time it rains, poisoning the fish. More bananas produced per year means more pesticide and a higher cost borne by fishermen, but the growers have set banana prices and production levels based on their own costs alone.

How could we fix this? Maybe the farmers negotiate a way to compensate the fishermen, or the government imposes a tax on bananas. In either case, the growers must adjust their price or production levels in a way that minimizes the costs imposed on fishermen.

There are a few levers governments can pull to address market failures. The book lays these options out in a handy grid.

Going back to our car example above, you could avoid pain at the pump and reduce your carbon footprint by purchasing an electric vehicle. But they’re expensive, so the government has offered subsidies to lower the total cost in order to encourage buyers. When those subsidies went into effect, Tesla lowered its prices to make more vehicles eligible, sending its own message to competitors entering the space.

Now, insuring that car is a whole other case of market failure, but we’ll talk more about that below.

Social dilemma: A situation in which individual actions, by companies or people in a market, can lead to inefficient outcomes, worse than if everyone had worked together.

External effect: When a given action imposes costs or benefits on an outside party, not considered by the person taking the action. These effects can often lead to market failure.

Asymmetric information can lead to conflicts of interest and market failure, and we see that a lot in the insurance market. Just look at this scene from “Seinfeld.” But moral hazard happens all over the place, even contributing to 2023’s historic bank failures.

In Chapter 12, we’ll learn about why the magic of markets doesn’t apply to everything and the role of the government in the economy.

Econ 101 is a production of Marketplace, a listener-supported public journalism outlet. Consider making a donation to support our mission to make people smarter about the economy, tech and the world. Your donation today makes for a better Marketplace tomorrow.

This course was written and edited by Ellen Rolfes, Erica Phillips, Tony Wagner and David Brancaccio. It was originally published in February 2023 and updated in November 2024.

Revisit previous lessons:

Chapter 1: The relationship between capitalism and income inequality

Chapter 2: How game theory explains rational decision making

Chapter 3: How policymakers and economists assess fairness and efficiency

Chapter 4: How an economist finds balance between work and leisure

Chapter 5: What is an “economic rent” and how does it influence working conditions?

Chapter 6: Why companies often pay workers more than minimum wage

Chapter 7: A primer on supply and demand and how firms maximize profits

Chapter 8: How firm competition impact consumer prices and worker wages

Chapter 9: Understanding credit markets and how they can perpetuate inequality

Chapter 10: Why banks have the power to create new money