When a struggling mother of two in Milwaukee hits hard times, she turns to a local welfare office for help — a welfare office outsourced to a private, for-profit company. Inside, staff preach the power of work, place people into unpaid “work experience” and enforce work requirements for welfare recipients, all in the name of teaching self-sufficiency.

But who’s set to benefit most? That struggling mother or the for-profit company she turned to?

Host Krissy Clark takes listeners into the world of for-profit welfare companies to examine America’s welfare-to-work system, work requirements and the multimillion-dollar industry that’s grown up around it.

The Uncertain Hour: S6 E1 The Dream Script/Transcript

Note: Marketplace podcasts are meant to be heard, with emphasis, tone and audio elements a transcript can’t capture. Scripts may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting it

Krissy Clark

I’ve spent a fair bit of time in the last few years getting tours of for profit welfare offices….. Like this one… in Milwaukee, Wisconsin… where a video of a corporate motivational speaker is beaming down on me from a TV screen in the lobby

Zig Ziglar

Look yourself in the eye and with excitement and enthusiasm say, “I love my job because they pay me for working there” (continue mumble track under next track)

Krissy Clark

If you’ve never heard of a for profit welfare office before? Me neither… until I started reporting this story. But back when Congress passed so-called “welfare reform” in the nineteen nineties… and made work a requirement for getting certain types of government aid? That same law also allowed the government to turn to private companies, to implement and enforce those work requirements. Ever since, offices like these have popped up all over the country.

Zig Ziglar

Tomorrow morning, get back in front of the mirror just before you go to work get back in front of the mirror and repeat the process again with excitement and enthusiasm. “I love my job because (fades under next track)….”

Krissy Clark

This office I’m in, with the motivational video droning in the lobby. It’s run by a multi-billion dollar, multi-national company called Maximus. Since the 90s, Maximus has helped governments run welfare offices in more than a dozen states. This one here in Milwaukee has turned into something of a cathedral for the glory of work. A cathedral with fluorescent lighting and cubicles and TVs.

Zig Ziglar

Everything really does begin with you.

Krissy Clark

Maximus and companies like it have, over the years received hundreds of millions of government welfare dollars for running welfare to work programs, and ideally, getting people out of poverty and into jobs, including this person

Quanesa

Quanesa Simpson. I’m 21. Of course I stay in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Krissy Clark

I met Quanesa on my first tour of Maximus back in December 2019. She has big hoop earrings, long braids, and a big smile. When she first applied for welfare. She didn’t know she was going to be interacting with a private money making business. She just applied for government aid and the state of Wisconsin sent her here to this bland Maximus office building. By the time I’d met her, she had been part of the program for almost two years… (Speaking to Quanesa) And what are you doing here today?

Quanesa

Today I’m having a meeting with Delonte. We’re going over my resumé and kind of trying to move forward to see kind of where I wanna go as far as a job.

Krissy Clark

Delonte is Delonte Carter, black turtleneck, close cropped hair. He works for Maximus as a job developer trying to help people like Quanesa find work, so they don’t need welfare anymore. When I drop in, there are drafts of Quanesa ‘s resume fanned out on the lawn taste desk. And he’s helping her with the struggle that’s faced job applicants across the ages: how to get a resume down from many pages to one.

Delonte

Like that was the main thing when she came she’s like, Okay, this is what I have. And I know we can tweak it. But this resume is definitely going to be that first stepping stone and getting her connected to some really good opportunities.

Krissy Clark

You’re nodding.

Quanesa

I was like mhm exactly right.

Krissy Clark

Quanesa tells me she first turned to welfare, what’s officially called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families for the reason a lot of people do. She was poor, couldn’t support her family on her own, and had nowhere else to turn. Her tipping point came after her second child was born. She’d had trouble finding a job when she was pregnant. And she didn’t have a permanent home. She and her kids were temporarily doubled up with the mother of her baby’s dad.

Quanesa

It was very hard, you know, I didn’t have an income to provide for a newborn baby. I really didn’t have a stable home with… not working a stable job. So it was kind of like I need this now. You know,

Krissy Clark

For Quanesa it was unstable housing with a newborn baby. For others, it could be domestic violence, the death of a family member. The list goes on. When you don’t have personal savings or family to turn to welfare is the system we’ve designed to catch people when they fall. A system that’s supposed to help people get to a more stable place through employment, so they don’t fall so hard again, which is what this meeting Quanesa is having today at Maximus is all about. Delante the Maximus worker is helping her tailor her resume into something that can hopefully help jumpstart a career. (Talking with them) Can you show me your resume?

Quanesa

Yes. So do you want me to start reading it for you?

Krissy Clark

Just as you described. So at the top, we’ve got your name… Quanesa’s first draft had been pretty informal, below her name she’d written “I’m in need of a new start to provide for my family. I’m very flexible, caring, patient and of course hard working.” Delonte punches that up into an objective statement. Quanesa reads it to me.

Quanesa

Objective to obtain a position which allows me to utilize my skills to adequately assist individuals with day to day living needs, including home, health care and cleaning services,

Krissy Clark

Delante condenses a little more here cuts a few lines there. And they look the new version over.

Quanesa

the black and white on the paper, you know, it’s about me, but Delonte — all this format. He did that. So I appreciate that as well. Delonte helped me A LOT.

Krissy Clark

Delonte hands her a printout of the new one page version of a resume.

Delonte

So this is going to be yours. We’re going to act like this one didn’t even happen

Krissy Clark

He throws the old resume in the trash.

Delonte

Nice. So yeah, we’re excited.

Krissy Clark

As I sit in on this meeting, Quanesa is having with Delonte, she seems genuinely grateful for his help with her resume. For Maximus and the people who set me up on this tour, Quanesa’s resume is an example of how the company has helped set her on a path out of poverty and towards self sufficiency. But there was this one detail, I noticed at the bottom of Quanesa’s resume. A detail that when I looked at it closely, made me wonder how much Maximus’ Welfare to Work program really helped Quanesa or whether Quanesa would have done just as well without it. It’s a detail I kept thinking about that would take me on a recording journey that would eventually cast out on some of the claims these private companies make… and doubt on the whole Welfare to Work model that our country’s long embraced, and that some want to expand.

Krissy Clark

Welcome to The Uncertain Hour, a show from Marketplace about obscure policies, forgotten history, and why America’s like this. I’m Krissy Clark, this season, the Welfare to Work industrial complex, look for job

News tape

// Look for a job, get a job, all of that. // should be required to work// an obligation to work// get out there and work! // / looking for a job, have a job, or be participating in a job training program. > <Trump: It’s time for all Americans to get off welfare and get back to work. You’re gonna love it!

Krissy Clark

We’re asking who this system profits.

News tape

The push for privatizing welfare systems has already spread across the country.

Krissy Clark

Like really profits.

News tape

A contract, which could be as much as $2 billion to run the state’s welfare services, total company revenue for fiscal 2022, increased to $4.63 billion.

Krissy Clark

We’re looking at who this system leaves behind,

Voices

I’m a big dollar sign for them // you would just get the job and lose it because you have no way of providing a way to get there, you have no way of providing clothes// honestly i kind of feel it was hell // i would go home and i would cry// it was very demeaning// it’s like, how can i explain it? The way I feel sometimes? I feel like a hamster in a cage

Krissy Clark

And we’re going back in time to discover the long fraught history of where this Welfare to Work system came from.

Archival tape

We challenged the right of a welfare program // To quit jobs at will and go on relief like spoiled children //And I won’t mention the ethnic group involved, but // This is what’s wrong with welfare now. There’s too many people that can do the work, they stay home and sleep

Krissy Clark

There’s nothing more American than the rags to riches success story. The idea that with a strong work ethic, you can climb out of poverty and do anything. So politicians have found it easy to sell welfare work requirements. In fact, some state and federal lawmakers are pushing to put new or tougher work requirements into even more programs like food stamps, Medicaid and government housing assistance. I wanted to understand how our welfare to work system actually functions today, and how our tax dollars are spent. There are around 1 million families on cash welfare in the US right now. So what does this Welfare to Work system feel like up close? Does it actually help people escape poverty? Or have the private companies that increasingly run our welfare system created their own cycle of government dependency? In this episode, I’m going to take you inside one Welfare to Work program in Wisconsin. A state that is and long has been a test kitchen for the Welfare to Work philosophy and the multibillion dollar industry that’s grown up around it. Chapter One: The Dream.

Katheedre

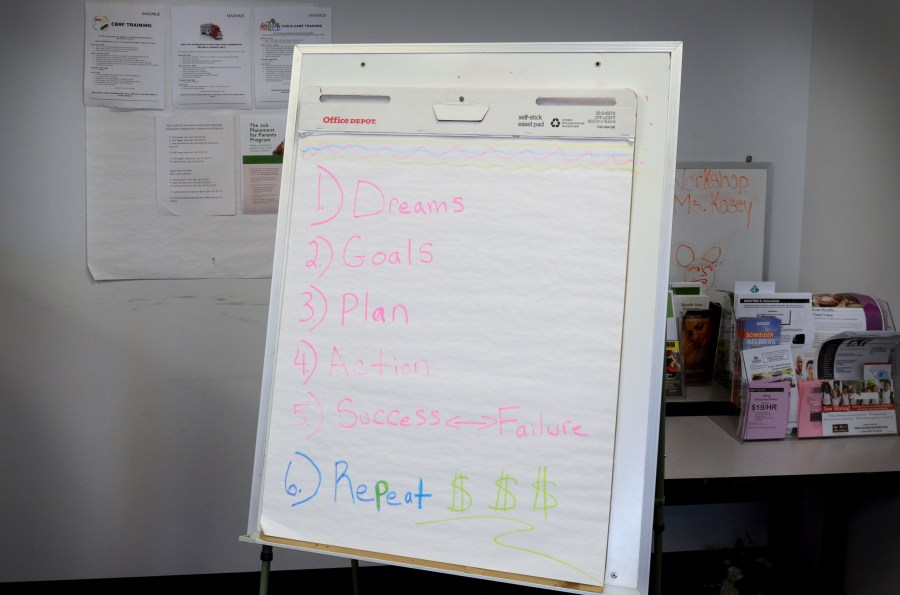

So if you can kind of look at our board is basically starts off everything starts off with a dream.

Krissy Clark

Everything starts off with a dream. That’s the message we’re all here to learn. I’m gonna get back to Quanesa’s story in a bit. But first I want to give you more of a tour of Maximus, that multinational for profit company that runs the welfare office where I met Quanesa in Milwaukee. Down the hall from where she was having her meeting, there was a class Maximus was running. When I stoped in, a Maximus employee named Katheedre Sea is standing in front of a whiteboard with a flowchart. It starts at the top with the word dreams in big pink letters, it ends at the bottom with a bunch of green dollar signs. She’s explaining the steps in between.

Katheedre

We all have a dream from where it was little whether we get older, and then we make those dreams we turn them to goals.

Krissy Clark

Katheedre is talking to a few women sitting around some desks. The women are quiet. The expressions on their faces seem caught between cautiously interested and suspicious. They’re here in this conference room listening to Katheedre’s lecture, because they have to be here, according to federal law.

Katheedre

So we got dreams. After that we make it into a goal. After that, we change it into a plan.

Krissy Clark

Each woman here in this class today is a mother who’s poor. Each woman here applied for temporary assistance for needy families to make ends meet. And to get that help each woman here has been required to come to this conference room five days a week for up to four weeks to take this class called Career Pathways. It’s one of many things that people on welfare are required to do these days. The goal of this class and pretty much everything Maximus does for the welfare system, is to motivate, prepare, and get these welfare participants into a job. That’s the priority. ASAP.

Katheedre

So what we’re doing right now is we’re filling out a form about their goals and what they want to kind of go into

Krissy Clark

Katheedre passed out some papers to our welfare students. Worksheets with prompts. What’s my dream job? What do I want to be doing in five to 10 years. I wasn’t allowed to use the women’s names for privacy reasons. But a few of them shared their answers with the group. First, a woman in a thick brown winter coat lined with fake fur, because it’s December in Milwaukee.

Woman 1

I plan to… I want to be a nurse. So I’m gonna go into the RN program. That’s my main goal.

Krissy Clark

Then another woman, despite the cold, she doesn’t seem to have a coat with her just a black hoodie.

Woman 2

Basically, my dream is to go to college, and put the position behind myself where my baby will always have something to fall back on.

Krissy Clark

Go to college, become a nurse, start my own business, get to a place where my family will always have something to fall back on. The dreams I heard from these women, and from lots of people I’ve talked to who’ve turned to the welfare system at some point, they’re big dreams, long term dreams about finding ways to move up and out of poverty. The kinds of dreams America loves to tell stories about and that usually takes some time and patience and education to achieve.

Joe

You guys are in the right place.

Krissy Clark

A man with a trim goatee and a dark pinstripe suit has been hovering in the doorway, as I sit in on this class. His name is Joe Murphy. And he helped design this work readiness curriculum. Joe is a vice president at Maximus. Joe flew here from Atlanta to meet with me and kind of chaperone my visit. We dropped into this class to observe it. But now that he’s here, he can’t pass up the chance to talk directly to some of these women. He walks to the middle of the room and turns to the woman in the black hoodie.

Joe

And I see you have great, great opportunity you have a child, right? How old’s your child? So you’re a mom, and you’re taking care of your little child. So that’s your whole life right there too. Right? So you’re trying to change your life and make it better for her. I heard you say that. That’s an encouraging thing. You want to be an example for your child. Right? Exactly. A role model is important. That’s how we learn. So keep on doing that. Don’t, don’t stop.

Krissy Clark

Joe is a big believer in the power of a motivated individual to climb out of poverty with a job. That’s what the whole welfare system is based on today. The idea that welfare needs to emphasize work and require work. So people can move from a welfare check to a paycheck as Bill Clinton liked to say.

joe

All you need is a hand up. Because you guys are strong, I can see right? You guys are strong, and you guys can do almost anything. You just need to be guided in the right direction sometimes. We remember the goal is self sufficiency.

Krissy Clark

To make these participants more self sufficient. This class will go over job interviewing strategies, and the importance of punctuality, the difference between business casual and formal business attire, there will be diagrams and more worksheets and flowcharts. Advice on what employers are looking for in an applicant.

Joe

I’m finding more employers today, just so you know, are looking for people with a positive attitude, a can do attitude. And sometimes it’s just a mind shift. It’s a reframing of what’s going on in your life and some things that we go through our hardships. And those hardships allow us to persist, because we got over some of the hardships in the past, right? We’ve all been there. (A woman nods) You know where I was this morning? I was having coffee, reading inspirational things. I do that every single day because where I came from I’m hardwired to drift negative. Does that make sense? So I work every single day to stay positive. It’s hard because if I let, if I take my hands off the steering wheel, my car will go into the ditch. Is that helpful?

Krissy Clark

A few more nods. As skeptical as some of these women seem to be when I first entered the conference room, it’s hard to ignore Joe’s energy.

Joe

I see you taking notes. I see you’re left handed like I am. Okay…

Krissy Clark

Joe is making connections with the women now. He tells them his family received food stamps when he was a kid. Eventually he went to college, business school, became a consultant on Wall Street. And now vice president here at Maximus.

Joe

It’d be hard to believe that I came from this program. When you look at me I’m in a suit and tie I’m I’m not any different than you are things change, right? You can become anything you want to become. And do not let anybody tell you can’t become something, because that keeps you down.

Krissy Clark

You can’t really talk about welfare without talking about race. So I should probably point out, Joe is a white man. I’m a white woman. And most of the other women in this room are black in one of the most segregated cities in America. Meaning mileage may vary on how easy it is to become anything you want to become,

Joe

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. Alright. And it’s a true statement.

Krissy Clark

Now Joe’s handing out motivational aphorisms about hard work like candy.

Joe

The demon we swallow, I can’t remember who said that the demon we swallow makes us stronger

Katheedre

I preach that all the time

Krissy Clark

Katheedre, the career pathways teacher jumps in again. They’re on a roll. Katheedre talks about how she was once a welfare recipient herself.

Katheedre

Regardless of where you come from what you’ve been through. You can you can do it. I was in this very building two years ago, and filled out an application because I was encouraged and I got the job. So it it comes back to me like the ladies come back into the classroom. I did this I got a job.

Joe

You just hit on it. When somebody comes back in and got the job when they thought they couldn’t get the job. And they jump up in the, in the air because… I was on one program in New York City, the lady did a jump that I’ve never seen before. She said I got the job that I wanted and that is exciting. Another person she was literally crying. Because she got the job. I was crying because it brought everybody around her starting to cry. She said you know how long I’ve been looking for a job three years, and nobody helped me. So that’s the satisfaction we get as providers of these programs and making and helping individuals like yourselves because not only do we get a hand up and we encourage but people don’t understand steps or rungs on a ladder. So how do we help them get to the right ladder, you know, and climb the ladder.

Krissy Clark

At this point, there’s a genuine feeling of uplift in the room.

Joe

I like the smiles, looking smiles,

Krissy Clark

This gospel of work that Joe’s preaching, it sounds so good. It’s part of the American dream. That no matter where you come from, if you work hard and have the right attitude, you can do anything.

Joe

You guys are great.

Krissy Clark

But when I eventually sit down with Joe and some of his colleagues that same day, I start to get a very different picture. Joe and I sat down in another conference room down the hall from that career pathways class… (Krissy gets situated in the room) I’m going to move because my arm is not long enough for everybody. I’m just going to get as close to you as I can.

Joe

I’ve had too much coffee, by the way. Starbucks at 5:00.

Krissy Clark

The thinking behind handing welfare over to companies like Maximus was that they could do better than government bureaucrats at getting people into jobs because they already had a business mentality themselves.

Joe

We look at it from the perspective of the employer. We look at the employer as a customer.

Krissy Clark

Joe’s colleague, Ric Ybarra explains to me that a big part of what Maximus does is work with local employers to find out what job openings they have, and then help fill those jobs with welfare recipients.

Ric Ybarra

The biggest question that we get is, are you sure that this is free? They’re kind of like, okay, sounds too good to be true to have a whole team working on my behalf and it’s not costing me anything. We serve as an extension of their HR, essentially.

Krissy Clark

An extension of their HR because Maximus is actively recruiting people to work for those employers rather than the employers having to do it themselves or pay a staffing firm. And Rick says historically low unemployment rates in the last few years, even pre-pandemic have made Maximus’ services even more attractive to companies, especially in industries that have high turnover and need lots of workers,

Ric Ybarra

employers across the country. They need people. They need folks to apply. They need folks to follow up on those applications. And they, you know, here in Wisconsin, we are facing a labor shortage just because of the aging demographic of our workforce. So we were already in a position that, you know, we needed to fill the pipeline with talent.

Krissy Clark

But Ric is quick to point out the job pipelines that Maximus specializes in filling, they’re for pretty low skilled work.

Ric Ybarra

If it’s an employer that’s looking for, you know, high level talent, you know, accountants and MBAs. You know, we’ll be honest, that’s not the participant base that we have.

Krissy Clark

Most welfare participants are young mothers, often without college or even high school degrees, and the way things have been set up since welfare reform, it’s hard to attend college or even get vocational training that lasts more than a year, while still fulfilling all the program’s work requirements. College classes often don’t count as work. Ric and his staff, they mostly pitch their services to companies with a lot of entry level positions, customer service, home health aides, packing and assembly work at warehouses, jobs that don’t pay much. Ric says those kinds of jobs are a great first step for Maximus’ welfare recipients, or what Ric calls his talent pool.

Ric Ybarra

By employers coming through us, now they’ve opened the door to a talent pool that they hadn’t necessarily looked at previously, that looks like it has the makings of really filling your talent needs.

Krissy Clark

And for Joe and Ric, and many believers in this model, it’s a virtuous circle, a win win. Employers get workers, welfare recipients get jobs, and hopefully, one rung higher on the ladder out of poverty. But as I listened to Ric and Joe make their pitch about serving up welfare recipients for free to worker hungry businesses, and setting them up into low skilled low wage jobs, it was hard to square that, with the motivational pep talks I’d heard Joe giving in that class he took me to. This version had less to do with helping poor mothers achieve their dreams. It was about serving a completely other set of interests, local and national businesses that need workers. I kept thinking to myself, what’s welfare actually for? Can you serve both these things at the same time? For Ric and Joe, their answer was a definite yes. And to illustrate this, they set me up with someone who just gone through the process herself. Quanesa Simpson, the woman you heard from at the top of the show, with that detail on a resume that caught my eye. Where did that resume take her? That’s after a break.

Ric Ybarra

So I mentioned earlier that we had arranged… we have pre-approval to meet with a program participant, Miss Simpson, and one of our job developers, Mr. Delonte Carter. Miss Simpson, you know, whatever you’d like to speak to in terms of your experience with, with the program where you are now, what you went through.

Krissy Clark

So remember Quanesa from the beginning of this story? The way I got to sit in on her meeting with Delante was because Ric and Joe from Maximus had specially arranged for me to get a glimpse into the job services they provide, their welfare clients. So what did Maximus actually do for Quanesa? Quanes told me that when she came to Maximus and first started getting her welfare check, the money on its own helped a lot. She was getting $653 a month in cash assistance, more than the national average for a family of her size, but still not much to live on. She also qualified for other government health like food stamps and health insurance. And she says she spread whatever help she got as far as she could to meet the needs of her two kids.

Quanesa

I was finally able to get a place so you know my light bill, my children, so yeah, it was helping a lot.

Krissy Clark

But the welfare check, that comes straight from the government. As for the help Maximus itself provides, that’s where things get murkier. When someone like Quanesa applies for welfare and Maximus or anywhere in Wisconsin, one of the first things that happens, a lot of questions and assessments to gauge the person’s quote, employability. How immediately employable you are, will determine what kind of work activities you’ll be required to do to get your welfare check. The only way to get your full welfare check is to prove you did all your required work activities for the required number of hours, typically 40 hours a week. You might be assigned to go to that career pathways class to begin with, to learn how to be quote, job ready, you might be assigned to apply for jobs and turn in documentation for each job you applied for. Delonte, the Maximus worker who was helping Quanesa with her resume, explains that another kind of work activity that’s common for welfare participants is called work experience.

Delonte

So like when Quanesa came in, I was able to help her get into a work experience placement.

Krissy Clark

Basically unpaid work you’re required to do at a local business or charity to earn your welfare check. Quanesa’s work experience was doing mostly janitorial work at a food pantry and community center.

Quanesa

I worked in a pantry, office cleaning..

Krissy Clark

She had to put her baby in daycare while she was doing the work. Maximus connected her with a government program that helped pay for childcare. Quanesa says at some points, she was assigned to 40 hours a week of work experience at the food pantry. If you divide that into her $653 welfare check, she was essentially making just around $4 for each hour of required work activities she was performing. Way less than minimum wage. But Quanesa was determined to make it work,

Quanesa

You know, I pushed so hard for a $653 check. You know, for 40 hours a week. I’m like I can do this.

Krissy Clark

And all that mandatory labor for such little money, it had a larger goal according to Delonte. He says these work experience placements are all about helping welfare participants get more experience to put on their resume, kind of like an unpaid internship for being a janitor.

Delonte

She can gain more skills so she can be more employable.

Krissy Clark

And six months later, she got an actual paying job through a company that Maximus works with to provide talent for their pipeline.

Quanesa

Yeah, I got the job and I was just so happy. Yeah. (And what was it for?) Clean power.

Krissy Clark

This job was also in cleaning. She’s a custodian at a physical therapist office.

Quanesa

I just clean you know, take out the garbage, wipe down equipment, mop floors, you know, it’s pretty simple work and I’m thankful for it.

Krissy Clark

The job started at $13 an hour for four to five hours a day. Sometimes she filled in as a supervisor and got $1 an hour more. And because of the way welfare works, once Quanesa got this part time paying job, her monthly welfare check got reduced to just a couple hundred dollars, then to $50. At the job, she was making somewhere between about 1,000-1400 dollars a month, more than she ever got on cash assistance but still not enough to put her family over the poverty line.

Quanesa

Like Delonte was just telling me it’s all about growth. So if I can work harder to get more, then that’s what I’m gonna do. Definitely.

Krissy Clark

Joe Murphy, the Maximus VP and my chaperone jumps in.

Joe

Nice to see you. Hey, Delonte. So you’re actually–I heard how much money you’re making, right? After taxes and all that. That’s good. That’s good for you. Congratulations. And how do you feel now that you’re going to work? Do you feel good about yourself?

Quanesa

Yeah, I love going to my job. You know, I’m ready. I feel like, you know. Just being able to know that I’m working hard for everything that I receive and being able to do more month to month, you know, take my kids to the zoo, or just different activities that I couldn’t do before. (Joe: And do you feel good about yourself?) Definitely. Yes.

Krissy Clark

I can feel Joe going into motivational speaker mode again,

Joe

Feels good to be out working with people

Quanesa

Yes, working with people and different experiences, talking to meeting new people every day, basically, you know, different environments.

Joe

And you know what I’m hearing from you. And I’m just I’m just what I’m hearing you say, I know that if I work hard. If I work harder, I become better. I can make more. Did I hear you say that?

Quanesa

Definitely yes. Because that’s what I’m looking forward to do it.

Krissy Clark

And in fact, that’s part of why Quanesa is here today, to figure out how to make more money. Because cleaning isn’t what Quanesa wants to do forever…. What’s your dream job?

Quanesa

My dream job oh my god. So I’m kind of considering if I want to do… I know I want to further my education. The first thought was to be an LPN, a licensed practical nurse.

Krissy Clark

She recently got trained as a certified nursing assistant, a CNA in a short term program through Maximus, so she knows how to feed and bathe patients, help them use the bathroom, but that’s grueling and pretty low paying work to do. She’d need a lot more training to become a licensed practical nurse. So she’s here in a meeting with Delante to figure out her next steps in the meantime. Delante and Joe seem to be earnestly rooting for Quanesa. And from a certain angle the help Maximus has given Quanesa seemed clear. Since she’d applied for welfare, she’d earned her GED, gotten trained as a nursing assistant, gotten some work experience, a job, and now some resume coaching for an even better job. But here’s where that moment happened, the one I played you at the beginning of this episode, when Delonte spruced Quanesa’s resume up, got it down to one page, and threw the old version in the trash.

Delonte

We’re going to act like this one didn’t even happen.

Krissy Clark

That’s when I noticed that detail near the bottom of her resume. It was on all the different versions. And like I said, it suggested a more complicated story. In the part where she listed her professional experience, one of the oldest entries from June 2017 to June 2018 was her working for a local company as a cleaner.

Quanesa

I was cleaning Airbnbs. So that was in 2017. So that was a while ago.

Krissy Clark

Which was a little confusing to me, because that would have been before she was on welfare. And I’d thought that part of what I just been told was that one of the key things Maximus had helped Quanesa with was to get her valuable work experience to build her resume. That that’s what all that unpaid cleaning she’d had to do with the food pantry to get her welfare check was supposed to be about. I thought maybe I was getting the timeline confused. Maybe she had gotten that cleaning job through Maximus too while she was on welfare, which in Wisconsin is called W-2. Was that through W-2?

Quanesa

No, no, no. Yeah, that was the year before that it says, yeah.

Krissy Clark

Okay, so she’d had that cleaning job before she went on welfare. And then there was another job I noticed on her resume, also before she was on welfare, where she also did cleaning at an assisted living facility. How did you find those jobs?

Quanesa

Friend of the family or something like that, you know,

Krissy Clark

So as excited as Quanesa was when she got her current cleaning job through Maximus, after she’d done hours and hours of mandatory unpaid work experience as a cleaner. I started wondering what exactly Maximus’ work programs were actually doing in the midst of all this?Were they giving her the help she needed the most?Quanesa told me she appreciated what Maximus had done. The interview coaching, the help they’ve given her with her resume. She said before she’d come to Maximus, she’d had some trouble in interviews because of a crime on our record from when she was a teenager. She says Maximus helped give her confidence to push through that and connected her with companies that were okay with her background. Still, as Quanesa’s resume was making clear, she’d already gotten multiple other jobs with that crime on her record, before she’d crossed paths with Maximus. Low paying precarious jobs, doing cleaning and caregiving work that had left her without any personal safety net. That’s part of why she turned to welfare after her son was born. And now, after going through Maximus’s Welfare to Work program, Quanesa seemed to be doing similar work to what she’d done before she was on welfare. It paid a little better, but not much. It didn’t offer health insurance. She still qualified for food stamps, and state medical benefits. Maybe Ric and Joe, the manager and VP for Maximus, can tell from my face that my brain was churning through all this as we talked. Ric quickly spoke up.

Ric Ybarra

So one of the points that I wanted to kind of interject here is as Ms. Simpson has indicated, you know, she… we were able to connect her with an employer that’s hiring, and that’s offered her position and she’s doing great there. However, just because she now has employment, our services don’t stop there. And that’s the purpose of this meeting is you know, Ms. Simpson has trained in the healthcare sector, as a CNA. So our goal is, even though she’s working now, is to get her into that sector where she trained and where she has interest. So Delonte is meeting with her now as an employed individual looking to get her connected to her career pathway of choice. So while the employment is a very good thing to have right now, it’s not that long term goal.

Krissy Clark

Ric and Joe soon ushered me out of the cubicle where Quanesa was having our meeting. But after we left, Ric had more to say about all the good things Maximus was going to help Quanesa achieve.

Ric Ybarra

So as in the case of the young lady that you met earlier that’s working with Delonte it isn’t first job and out. It’s this job and up, you know, let’s look at that next career pathway opportunity for you.

Krissy Clark

As Ric’s saying this, an announcement comes over the PA interrupts his talking point. Joe doesn’t want Ric’s point to be lost.

Joe

I think that was an important point. Could you do that again?

Ric Ybarra

Okay. Yeah, yeah, it isn’t just first job and out, it’s this job and up. So that’s, that’s important, you know, for, for us to understand and to realize, and, and this is what we put into practice each and every day. And the participants that we’re working with, are made well aware of the fact that, you know, once you’re connected to employment, it doesn’t stop there. That’s a new beginning. And that’s a new beginning on, you know, hopefully, you know, an upward track that’s going to lead to even greater things.

Krissy Clark (on phone)

Hi, is this Quanessa?

Krissy Clark

Recently, I caught back up with Quanesa to see where she is now. It’s been more than three years since I first met her. A pandemic happened in between, she left welfare, but her dream job in nursing, she tells me that didn’t work out. She stayed at that custodian job at Clean Power for a couple of years. She got a small raise, was eventually making between $14 and $16 an hour depending on the shift. But she could never get more than part time hours. So she relied on food stamps, state health insurance to make ends meet. The job was far from her house and when her car started having trouble and it couldn’t get her to work reliably, she had to leave that job at Clean Power. She went back on welfare, at Maximus. Her required work activity this time was unpaid work experience at a childcare center. Eventually, she got hired there as an assistant teacher. So she left welfare again. She says the childcare work is decent. She gets $16 an hour, still no benefits. She needed more to support her two kids. So she got another job as a cashier at Dollar Tree for 13.25 an hour.

Quanesa

I work 40 hours for the childcare and then for dollar tree down I do about 26 hours.

Krissy Clark (on phone)

Oh my gosh, 40 hours a week at the daycare and then 26 hours on top of that a week?

Quanesa

Yeah.

Krissy Clark (on phone)

That’s a lot of hours.

Quanesa

Yeah, you know, I’m just right now I gotta go. And I’m trying to push through to make it to that. So I keep doing what I need to do.

Krissy Clark

She and her kids still have to rely on state health insurance. She’s making less than $4,000 a month, working 66 hours a week. Still, when she looks back at her time on welfare with Maximus, she says she appreciates it.

Quanesa

I’m just thankful for everything that I got out of it.

Krissy Clark

But here’s something I didn’t learn until after I’d visited Maximus back in 2019. Something my producers and I discovered much deeper into our reporting, after we obtained hundreds of government records that gives all this more context. Maximus got something out of Quanesa too. According to the contracts the state of Wisconsin has with the private companies that now run many of its welfare to work programs, when one of their participants gets a job that lasts at least a month and meet certain basic requirements, the state rewards the contractor with a special payment called a performance outcome payment. In the case of Maximus in 2019 when Quanesa got her job at clean power, Maximus would have been awarded a little more than $2,600 per participant when they got a job. Because Quanesa’s job lasted more than three months, Maximus could have gotten another payment for the same amount. Companies can only get these kinds of payments once a year for each participant. But after her car trouble when Quanesa lost her cleaning job and went back to welfare, and then got her job at that daycare in 2022 and kept it for more than three months. Maximus could have claimed even more performance outcome payments for that, for at least another almost $6,000. Meaning that because of how these welfare contracts work, Maximus could have claimed altogether about $11,000 based on Quanesa getting those jobs. Paid to Maximus with taxpayer money. And that was for just one person.

In the last 10 years, the state of Wisconsin has paid Maximus of over $14 million just based on these kinds of performance outcome payments according to our analysis of state records. That’s money that mostly came from the fact that in that time, a total of a few thousand of their welfare participants got jobs that lasted at least one month or at least three months. Other private welfare companies nonprofit and for profit have also taken in many millions of dollars in these performance payments over the years. And that performance outcome money is on top of the tens of millions of dollars the state has paid companies to cover the costs of just administering the welfare program, processing applications, assigning and enforcing required work activities, offering job readiness classes. I should say these performance payments have a goal that makes sense in theory. They’re supposed to incentivize contractors to help get people jobs and to help get jobs that last for at least a few months. But what exactly have these companies accomplished for all that money? Well, in the case of Maximus and Quanesa, Quanesa says the company’s Welfare to Work program gave her more confidence looking for jobs. She learned a ton from Delonte resume advice, and she did find employment while she was going through the program. But still, the first job she got through Maximus was doing the same kind of work she’d already been doing before she came to Maximus. Work that paid so little and offered so few benefits, she still relied on food stamps to get by. Work that left her financially unstable enough that when her car broke down, she had to leave her job. And the second time she went through Maximus’ program the job she got paid little enough that she has to work two jobs to support her family. And they still have to turn to the government for health insurance. When my producers and I tried to follow up with Ric and Joe from Maximus about all this recently, neither agreed to another interview. A PR person working for the company directed us to the state for comment, saying that Maximus doesn’t set program policies, the state does. When we asked the state agency that oversees welfare in Wisconsin for an interview, they declined too. In an email a spokesperson pointed out that Wisconsin’s welfare system is nearly 30 years old, and has never been updated by the legislature since its inception. But the current administration under Governor Tony Evers is quote, “working to make positive changes to the program to better serve the needs of its participants, and has plans to perform a formal evaluation of the program to formulate recommendations for changes before the next contracts with private welfare agencies start in 2025.” I also asked Quanesa about this setup when I talked to her on the phone recently. I told her that Maximus was a for profit company that makes billions of dollars in revenue. That a whole lot of that money comes out of government coffers. And that some of that money came directly from managing welfare cases like hers. I told her that based on the state records I obtained, if you calculate how much government money Maximus got for managing just Quanesa’s case and helping her find those jobs. And you compare that to the amount of money Quanesa herself, struggling mother of two, got in cash assistance, for the whole time she was on welfare. Maximus looks to have gotten about as much money if not more than Quanesa. She thought about this for a moment, and said she wasn’t too surprised. That’s what businesses do, try to make a lot of money. And ultimately, that’s what she was trying to do.

Quanesa

When I was there I was working on myself and trying to get myself together to better my family. And that’s what I did.

Krissy Clark

Zooming out from Quanesa’s story, if you look at what’s happened since the 90s, when Wisconsin and states across the country put work requirements into welfare programs, and in many cases outsourced those programs to private companies. There’s not much evidence that any of it has had much broad success moving the needle on poverty. Whether those programs are run directly by the government, or by private companies. A comprehensive survey that RAND did in the early 2000s of dozens of studies of state welfare reform initiatives, found that programs with mandated work related activities can modestly increase employment and earnings in the short run. But in the long run, their impacts were smaller. Average earnings of program participants generally remained low, and not enough to move most of them above the poverty line. More recently, the research group Mathematica looked at several studies of welfare case management strategies with their focus on job readiness and work requirement compliance. And they came to a similar conclusion. The researchers found that quote, “the existing evidence is clear. These programs are mostly not effective at improving the economic independence of welfare participants.” Meanwhile, Quanesa is doing what she can to beat those odds. Working two jobs more than 60 hours a week.

Krissy Clark

That’s it for this episode. Next week, the next chapter in our series, a woman who turned to the privatized welfare system in her most vulnerable moment, fleeing domestic violence, and what kind of mandatory work she was told to do.

Darnetta Harris

I actually told the worker. I can’t do that. I can’t do that.

Krissy Clark

How how did they react when you said that?

Darnetta Harris

She was, like, Well, you won’t be getting no check.

Krissy Clark

This episode was written and reported by me, Krissy Clark. Grace Rubin, Peter Balonon-Rosen and I produced it. Our editor is Michael May.

Research and production assistance from Marque Greene, Tiffany Bui, Muna Danish and Daniel Martinez. Data wrangling by Elisabeth Gawthrop from APM Research Lab.

Betsy Towner Levine provided fact-check support. Scoring and sound design by Chris Julin. Jayk Cherry mixed our episode.

Caitlin Esch is our Senior Producer

Bridget Bodnar is Director of Podcasts at Marketplace.

Francesca Levy is the Executive Director of Digital.

Neal Scarbrough is Marketplace’s VP and General Manager.

Special thanks to Catherine Winter and Nancy Farghalli for their editorial wisdom – as well as Curtis Gilbert, Donna Tam, Reema Khrais, and Hayley Hershman.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

This season of “The Uncertain Hour” tells the unheard stories of real people affected by the welfare-to-work industrial complex.

Stories like these are seldom in the limelight. It takes extensive time and resources to do this type of investigative journalism … to help you understand the complexity of our economy and to hold the powerful to account.

We need your support to keep doing impactful reporting like this.

Become a Marketplace Investor today and stand up for vital, independent journalism.