Our experiment in remote schooling could improve education, if we do it right

This week on Marketplace, we’re talking about what’s changed in our lives in this year of pandemic and the lessons we’re taking into the future.

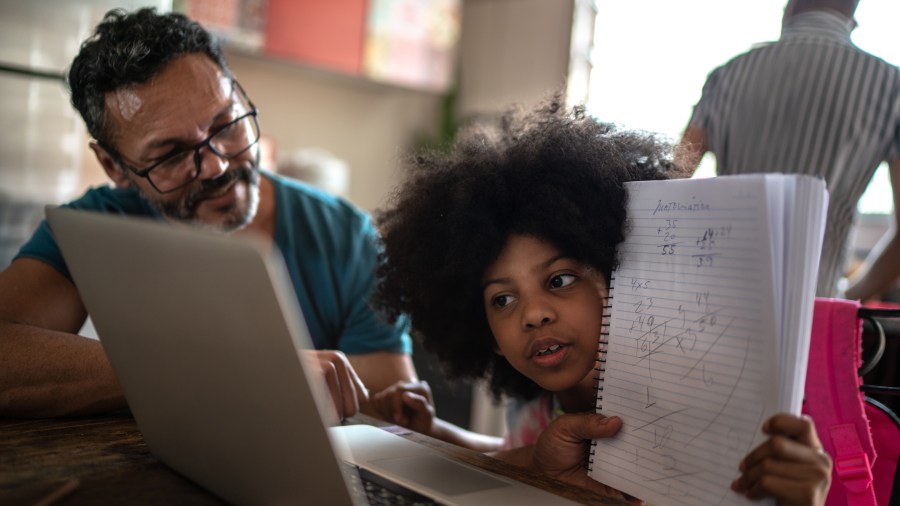

In education, the transition to remote learning exposed a deep digital and device divide, inequality among schools and a lack of preparation for online learning. But some of what we learned, no pun intended, could improve schooling in the future and prepare us for the next disruption. That will take money, political will and stamina.

Laura Ruderman is CEO of the nonprofit Technology Alliance, focused on Washington state. This year the group released a report called “Learning From Calamity.” The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Laura Ruderman: We actually released this report on Groundhog Day. And we were making jokes that it, that was quite appropriate because many of our recommendations are not new. They have been made over and over and over again. And the hope is that, like Bill Murray at the end of the movie, we can finally learn our lesson and be able to move forward.

Molly Wood: What are the elements of online learning do you think that could stick around, that could improve the education system?

Ruderman: Well, I think it’s very clear that elements will stick around. We have several school districts that are looking at starting online-only programs. Because there are students who are thriving in this environment. There are [Black, Indigenous and people of color] students who are happy not to have to deal with the racism that goes on in school. There are kids with social anxiety. So, we’ve heard that there are school districts in Washington who are looking at having some form of remote learning persist for those who want it. But in order to do that, you know, you need sufficient funding and support and training.

Wood: Let’s talk about sort of lessons learned. You’ve also said we have to remember that teaching in person and teaching remotely are fundamentally different things, but that we should instruct teachers in how to do both, right?

Ruderman: Yes.

Wood: Tell me more about that.

Ruderman: So I think that you’ve seen some schools try and bring back teachers into the classroom and video them and have them teaching, essentially, to an empty classroom, with all the students watching on Zoom. I think anybody who’s ever participated in a meeting in person versus run a meeting remotely understands that it is not a one-to-one translation. Your ability to focus on a live teacher standing in front of you in person, in a real-life room, we can do that for longer than we can stare at a screen. So, there’s just all of these different things that go into teaching remotely versus teaching in person that are just qualitatively different.

Wood: We talk a lot about the lack of devices and the lack of internet access for students and families. But that’s true for teachers, too. They’re not necessarily experts, or well-equipped themselves.

Ruderman: Absolutely. And that’s one of the things that we stress over and over in this report, is that while we talk about internet access for students and devices for students, our teachers need that, the same access to high-quality internet and high-quality devices. And the same kind of support for the remote learning. So, one of the things that we talked about in this report that some other states have done is what happens to IT support when you are looking at remote learning versus IT support for one building. So there are a lot of different aspects that are going to have to change in order for this to be successful. We looked at connectivity devices, IT support. But we also looked at nontechnical things like family-engagement coordinators and what you need to do in terms of support for educators and the differences in how they’ll teach. It’s really a full spectrum of issues that we need to start working on now. Because they will take time to plan and implement.

Wood: If you could just choose one or two [things], the most significant places to put energy and resources, is it internet? Is it devices? Is it training?

Ruderman: You know, the problem is that’s a little bit like asking a person who’s doing a jigsaw puzzle if they should do the frame or the interior, or just the upper left. The puzzle isn’t going to be complete without all of the different pieces. You can have the best device in the world. And if you can’t connect it to the internet, it’s a doorstop. You can have your students have great internet and terrific devices, and if you forget about your teachers, you have a problem. Right? So, they really are all interlocking pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. And that’s really important because the mess that this pivot was this time can be chalked up to a failure of imagination. But the next time, it will be seen as a failure of leadership if it’s this much of a mess again.

Related links: More insight from Molly Wood

One thing I’ve wondered is whether, in addition to there being fewer excuses for snow days, we might start to rethink the idea of school as a physical place. What if there are teachers or classes that are great for a kid but not located in their town? Or a star teacher who everyone wants to learn from, not unlike a college model?

Stacia McFadden is the chief information officer at the Lovett School, a private school in Atlanta. Like many schools, it’s operating with a hybrid model, where a lot of the students are there in person. But some are still taking classes virtually. So, their teachers are instructing both kids in the room and kids at home.

McFadden said they’re thinking about how the school might benefit from offering those virtual lessons to a wider audience.

“I think for independent schools, this is a creative way to look at how to possibly get more income. Because what if we offer a class that’s really good, that another kid doesn’t have access to either from another state, right, or even a public school, and they might want to pay for that class?” she told us. “So there’s ways definitely that we can keep this going. I think it would be smart of us to consider it.”

McFadden said if the school did that, they would have teachers who were totally dedicated to the virtual audience. That way, they won’t have to split their attention between the two groups. It’s sort of a way to scale education.

Who knows if that’ll be a widespread model anytime soon? But in times of great change, we plant the seeds of even more change. And lots more options are on the table now.

A Christian Science Monitor piece published Tuesday notes that a decent number of parents don’t mind remote learning, or they think it’s safer. An NPR/Ipsos poll conducted in February found that 29% of parents said they’re likely to choose virtual school for their kids indefinitely.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.