Massive online courses got a boost during the pandemic. Will it last?

When a couple of Stanford professors founded Coursera in 2012, they promised to democratize access to higher education by making courses from prestigious colleges available online. Nearly a decade later, many of us were thrust into the world of online education by the pandemic. Tens of millions of new users joined Coursera’s platform, some just looking for lectures to occupy their time, others seeking new skills in areas like machine learning and data science.

I spoke with Jeff Maggioncalda, the chief executive of Coursera. He told me that states like New York and Tennessee have also paid the company to provide free courses for unemployed residents. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Jeff Maggioncalda: Governments have realized that online re-scaling programs have a speed and scale and cost effectiveness that is just not really matchable. One of the exciting things after a year of seeing really growing inequality and many women dropping out of the labor force to take care of kids who can’t go to school, what we’ve been seeing on Coursera is the percentage of enrollments, especially in STEM courses, from women, has gone up from about 33% to 47%. Almost 50/50. So women are actually turning more to online learning. And as we think about the future of work, for states who are thinking about reskilling, being able to get your citizens access to jobs that maybe aren’t in your state is going to be much more possible with remote work.

Amy Scott: What kind of success rates are you seeing? I mean, have the unemployed folks who’ve taken these courses during the pandemic gone on to get jobs in related fields?

Maggioncalda: It’s hard to track altogether, and we’re still at the earlier stages. But there’s a program that we’ve been running with Google for a number of years. Google basically identified that there’s a lot of demand for IT support professionals. They put up the Google IT support professional certificate on Coursera [and] they have found that over 80% of graduates who get interviewed say that it has helped them with a job. I think they’ve placed many thousands of learners after having taken it. And so we’re creating more and more of these entry-level digital job programs that don’t require a college degree, and we’re very excited about it.

Scott: Coursera is now a public company — you had your IPO earlier this spring. I imagine that increases the pressure to turn a profit. How close is that?

Maggioncalda: Well, it doesn’t really increase the pressure to turn a profit. It does, of course, put a focus on: Will you be able to be profitable someday? So a lot of what Wall Street talks about is that next customer that you bring on, what is the expected revenue that you’ll get from that customer? And what’s the expected cost of serving that customer, so long as you can show that for, the marginal customer, it’s profitable? Most of Wall Street wants you to invest in growth. And so we don’t think that we’ll probably be rushing to profitability in the next year or two.

Scott: I want to talk about completion rates, which vary widely, depending on whether students are paying for the course or not. I think I read that for students who were taking free courses, the completion rate was about 10%. But more like 40% or 50% for those who did. Why do you think that is, and did that change at all during the pandemic?

Maggioncalda: Generally speaking, completion rates are related to how valuable it is for a learner to complete something. And as you might expect, if you’re trying to complete a college degree program, and you want to end up with a diploma, then you’re really going to try hard to complete it. So the completion rates among college degree programs on Coursera — we now have over 30 bachelor’s and master’s degrees that you can get fully online on Coursera — are up in the 90% range. So people are very committed, they really want to get that final certificate. I think people who are paying for courses, like you said, are completed at much higher rates, especially when paid courses are available in your company, because they want to show their employers, “Hey, I’ve learned this stuff.” The free courses are generally people kind of just watching a lecture here and there, and it’s a bit lower. I have to say, the more job-relevant the content is, and the more valuable that final professional certificate or college degree, the more likely it is that people stick with it.

Scott: So a lot of colleges had to figure out how to teach online this past year, professors who’d never done so before. I wonder if that’s a threat to your business.

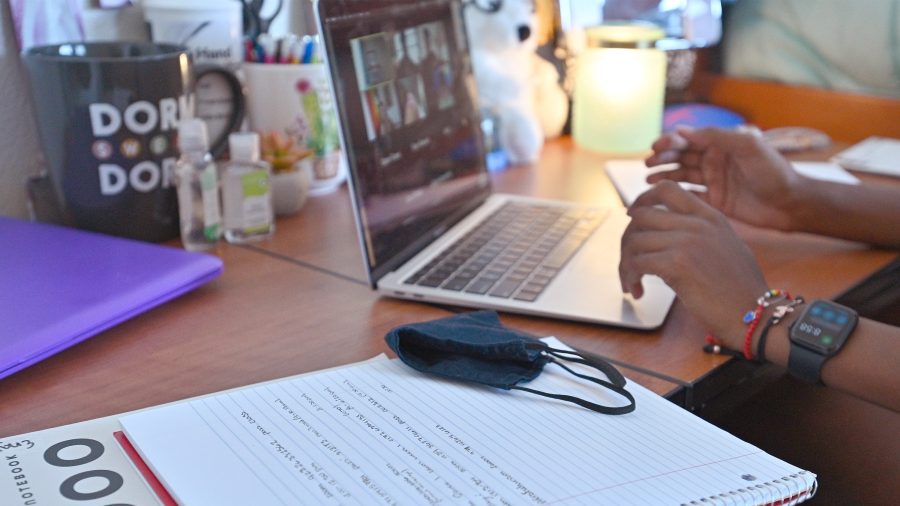

Maggioncalda: So far, it has turned out to not be a threat. I mean, to the extent that it would be a threat, I think it would only be a threat because it has been so difficult for so many professors and students who experienced online learning as, “Turn on the Zoom camera.” So the idea that online learning is one where you just take what was happening on a lecture stage and you simply do it in front of a camera, is not energizing to either the professor or the students. But what we have seen is that professors and students alike have realized, especially when it comes to digital skills, the ability to learn at your own pace, to do it online, to have hands-on practice as you go through the course, and to do it whenever you want to. You could do it in the morning, you could do it in the evening. That kind of flexibility is something a lot of people are looking for. So we’ve actually seen a much bigger interest and demand for online learning from both students and faculty who realize turning on a Zoom camera can be valuable for short periods of time, but really can’t be the backbone of online learning.

Scott: Why can’t universities just do this on their own, as many of them have tried to do recently? What does Coursera provide? Is it just the good lighting and the high-quality video?

Maggioncalda: Well, it might not sound really fancy, but a lot of what we provide is global distribution to a global audience, not only to individuals –– of whom there are 82 million on Coursera –– but also, we have Coursera for Business, Coursera for Government and Coursera for Campus, and serve 6,000 institutions around the world, where learning is happening inside of an institution. The biggest thing that we offer to our educator partners is that global reach. And of course, we think we also have really good technology that helps them create and deliver high-quality learning, especially hands-on digital learning, on a scale that they just couldn’t do on their own.

Related links: More insight from Amy Scott

About those customers: Maggioncalda says only about 10% of the company’s 80-plus million individual learners pay for courses.

I’m old enough to remember when MOOCs first became a much-hyped thing back in 2012. The acronym for massive open online courses has kind of faded with the hype. At the time, Coursera’s main competitor was edX, a nonprofit founded by MIT and Harvard. The two have taken very different paths since then, which Jeffrey Young recently wrote about at EdSurge. While Coursera became a unicorn company valued at nearly $7 billion when it went public, edX has stayed nonprofit and has fewer than half the users, though it has also seen more business during the pandemic. Another big difference: edX has made its platform open source, meaning anyone can access its code to develop their own courses for free.

And while New York and Tennessee are paying Coursera to train unemployed workers, workers are often on their own. Out of the 29 developed nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. ranked next to last for taxpayer-supported training. That’s according to The Wall Street Journal, which looked at why companies often don’t train their workers in new skills and instead fire them when their skills become obsolete. General Motors, Verizon and software company SAP provide recent examples. According to a survey by Accenture quoted by the Journal, although nearly half of executives worried about skill shortages, only 3% planned to significantly increase training budgets in a three-year period.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.