Controlling a video game with your mind isn’t just science fiction

It sounds like the stuff of science fiction, but now it’s just science. Brain-computer interfaces are making it possible for people and other sentient creatures to control technology with their brains.

Last year, Neuralink, the brain device company owned by Elon Musk, claimed it had trained a monkey to play the video game Pong using this technology.

Now there are a number of private companies and academic researchers trying to improve this technology for broader use.

AE Studio, a software development firm, works in this space. “Marketplace Tech” producer Daniel Shin recently visited its offices in Venice Beach, a neighborhood in Los Angeles, to test out a fun experiment — playing a video game with just his brain.

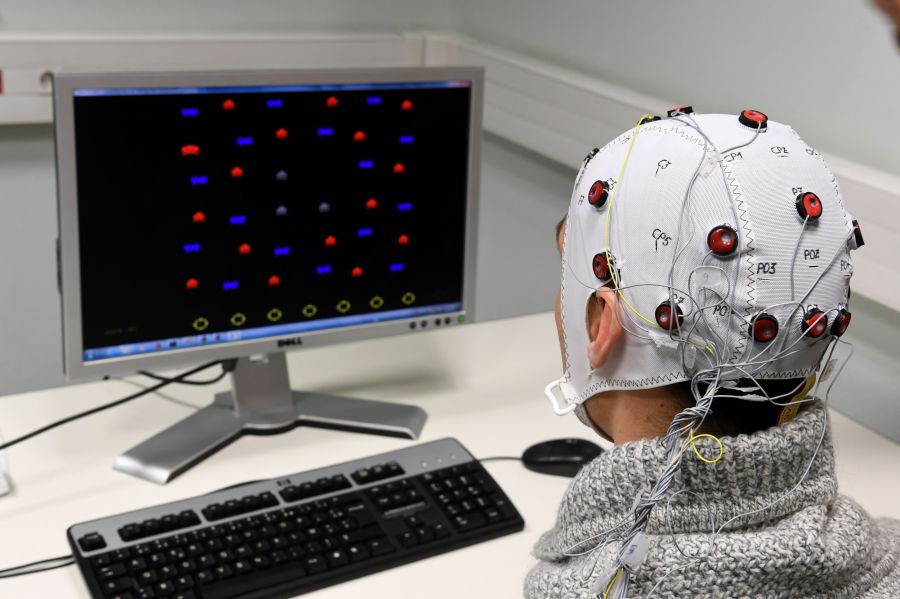

It’s a Wednesday morning at the offices of AE Studio, and I’m getting ready to do something I’ve only dreamed about as a kid — play a video game with my mind.

Sumner Norman is chief neuroscientist at AE Studio. He’s part of a team of scientists who design machine learning software for brain-computer interfaces, or BCIs for short.

He’s also calibrating this device to my brain activity. There are different steps involved, but one of the more important ones involves me thinking about moving while not actually moving, which is really hard to do.

“I want you to imagine that you’re right on the edge of literally jumping out of your seat to, like, you know, grab something on the wall,” Norman says.

But that’s an unfortunate reality for many physically disabled people. And as these interfaces get better, these devices can bridge the disconnect between thought and action and potentially give disabled people some physical agency.

“It can be simply the control of a cursor on a screen. It can be a robotic arm or a prosthetic for someone who’s lost that ability,” Norman says.

But there are challenges with these devices.

“These signals that we are recording are prone to be contaminated by different sources of noise,” says José del Millán, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Texas at Austin.

Interference could come from electromagnetic signals from nearby electrical devices or even involuntary muscle movement.

Researchers are also experimenting with inserting these devices into the brain. But these invasive interfaces have their own problems.

“The biological environment in the brain is pretty hostile to implanted electrodes, and they tend to not last particularly long,” says Karen Schroeder, a researcher at Columbia University.

Another part of the problem has to do with how our brains are constantly changing. And it can take weeks, even months, to train people to use these devices and to calibrate them once they’re tuned to someone’s brain chemistry.

Software developers like AE are working on brain interfaces that can adapt quickly so eventually they’ll have wider applications, such as mind-controlled wheelchairs or even mental health treatments.

“People are trying to use noninvasive stimulation to potentially treat psychiatric conditions like depression or anxiety … biofeedback type of applications for mood or meditation,” says Schroeder.

But back at AE Studio, I’m ready to see if I can control this video game with my brain. Norman is just about done calibrating my device, and after about an hour of work, I’m ready to play.

The idea is, I need to make a cute, green dinosaur jump over pixelated cactuses. Think of it like a very basic version of a Super Mario Bros. level.

While the whole demo wasn’t perfect, I still get a pretty decent score.

This experiment was not for commercial use, it was a fun way to test the technology. The main idea, though, is that this software could lead to practical, life-changing applications for people who struggle with physical disabilities.

Related links: More insight from Meghan McCarty Carino

And cool as it is, this tech has bigger implications than making game dinosaurs jump.

Ars Technica reported on the case of a man paralyzed by ALS in Germany who was able to use an implanted brain interface to communicate when he was no longer able to speak.

With several months of training, he was able to use his brain to select letters on a computer and spell out words to create short audio messages. He asked his caregivers for a beer, put on his favorite Tool record and asked his young son to watch the movie “Robin Hood” with him. It’s pretty incredible.

Researchers at the University of South Florida are also using this kind of tech to make brain paintings.

They don’t exactly compare to the works of the old masters, but the technique has potential, as a treatment, to improve concentration for people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Now, technology that can read our brains does raise concerns. I mean, targeted advertising is already creepy enough. Imagine if companies could actually track how our brains respond to content.

That’s a ways off, according to the Future of Privacy Forum.

But the time to start thinking about how to safeguard the data collected from our brains is probably before companies can read our thoughts.

The future of this podcast starts with you.

Every day, the “Marketplace Tech” team demystifies the digital economy with stories that explore more than just Big Tech. We’re committed to covering topics that matter to you and the world around us, diving deep into how technology intersects with climate change, inequity, and disinformation.

As part of a nonprofit newsroom, we’re counting on listeners like you to keep this public service paywall-free and available to all.

Support “Marketplace Tech” in any amount today and become a partner in our mission.