The James Webb Space Telescope is out of this world (rerun)

Hey everyone, we’re taking a short break today, but we’ll be back tomorrow with an all-new Make Me Smart. In the meantime, here’s a deep dive episode you may have missed, all about the James Webb Space Telescope. NASA released its first images earlier this month.

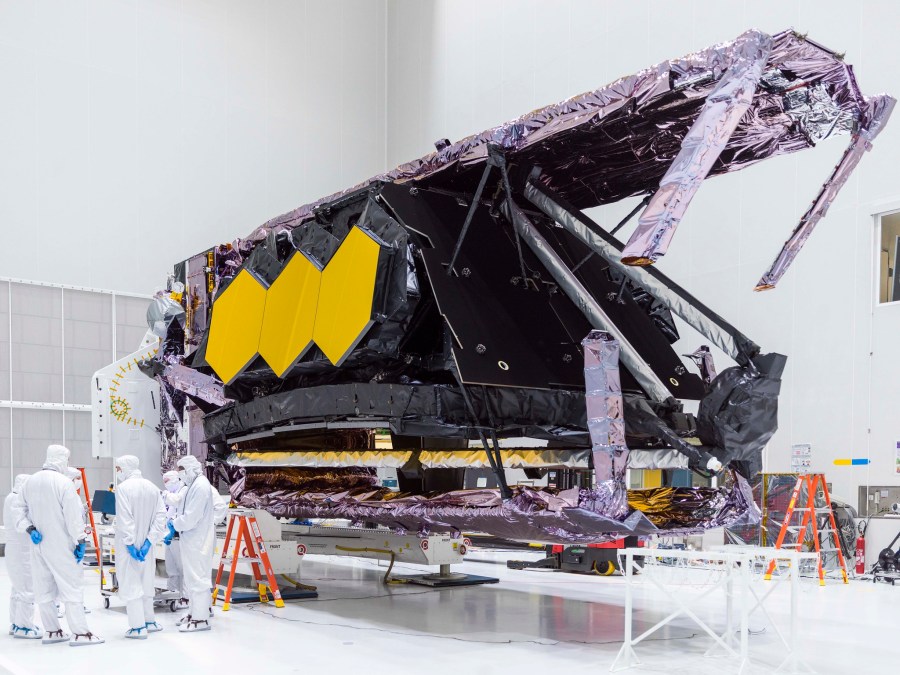

For the first deep dive of 2022, we’re going to space! OK, not really. But we’re talking about the most powerful space telescope ever. The James Webb Space Telescope cost $10 billion, a lot of tech went into developing it and we can’t stop obsessing over it. Neither can our guest.

“I cannot contain my excitement. It’s been a wild roller coaster getting to this point. And to have this telescope now launched in space, it’s just so thrilling for astronomers everywhere,” said Caitlin Casey, professor of astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin, who will be leading the biggest project on the JWST.

The telescope is expected to help researchers discover some of the most distant galaxies and study the atmosphere of planets outside our solar system to see if they’re habitable.

On the show today: what the JWST tells us about the future of public and private investment in space exploration.

Casey will also highlight the technological developments created by the JWST and its predecessor, Hubble, and how they’ve impacted industries from medical equipment to GPS technology.

In the News Fix, some companies have stopped predicting when they’ll be back in the office. Plus, an in-depth investigation into the House and Senate members who enslaved Black people. Later, we’ll discuss why some people want to tone down our use of the term “deep dive” and an answer to the Make Me Smart Question from the 2011 Nobel Prize winner in physics.

Here’s everything we talked about today:

- “James Webb Space Telescope Launches on Journey to See the Dawn of Starlight” from The New York Times

- Photo: the Hubble Deep Field

- “Global Space Economy Rose to $447B in 2020, Continuing Five-Year Growth” from the Space Foundation

- “NASA splits human spaceflight unit in two, reflecting new orbital economy” from Reuters

- “Surging Covid-19 Puts an End to Projected Return-to-Office Dates” from The Wall Street Journal

- “Rivian shares decline on 2021 production and executive departure” from CNBC

- Who owned slaves in Congress? A list of 1,700 enslavers from The Washington Post

Make Me Smart July 21, 2022 transcript

Note: Marketplace podcasts are meant to be heard, with emphasis, tone and audio elements a transcript can’t capture. Transcripts are generated using a combination of automated software and human transcribers, and may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting it.

Kimberly Adams: It’s been a while but here we go.

Kai Ryssdal: Oh my goodness. Really? First Tuesday back give me a break everybody. I’m Kai Ryssdal. Welcome back to “Make Me Smart” where none of us, maybe me, is as smart as all of us.

Kimberly Adams: Why just you?

Kai Ryssdal: I don’t know. I don’t know.

Kimberly Adams: Anyway, I’m Kimberly Adams, thank you so much for joining us. It’s been a while. So I’m happy to be back.

Kai Ryssdal: It is so good to have you back. It has been a long while and let’s just say at the gate, this will not be a normal episode. Here’s the deal. We had some kluging of schedules today, which is entirely my fault. So we’re doing this episode in two tranches, we’re going to do me and Kimberly for a little bit. Then Kimberly is going to do the interview by herself, which I’m really, really jealous about because it’s a cool topic –

Kimberly Adams: I’m so sorry.

Kai Ryssdal: – which I’ll let her tell you about. I know it’s so cool. And then I’m gonna be back for the second half of the show. So there you go. That’s what’s going on.

Kimberly Adams: Don’t blame yourself too much. It’s life.

Kai Ryssdal: Yeah, you know, I tend to do that. I tend to blame myself. Alright, here you go. Kimberly, you do it.

Kimberly Adams: Alright, so for this weekly deep dive, we are talking about something I am just obsessed over the James Webb Space Telescope, or hashtag JWST, it is the most powerful space telescope ever. It cost about $10 billion, a ton of tech went into developing this thing, and it’s really worth getting smart about because the success of this telescope tells us a lot about NASA and the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency and everything that’s going on with these government agencies, plus some things about the way that public versus private funding of space exploration is going right now. So here to make a smart on this topic is Caitlin Casey, a professor of astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin, who is approved to use the telescope and will be leading the largest project on the JWSt. Welcome to the program.

Caitlin Casey: Thanks so much for having me.

Kimberly Adams:Okay, how excited have you been the last couple of weeks?

Caitlin Casey: Oh, my gosh, I cannot contain my excitement. It’s been a wild roller coaster getting to this point. And to have this telescope now launched in space. It’s just so thrilling. So thrilling for astronomers everywhere. But I hope you know more broadly, the public too. I mean, everyone’s excited about this telescope. So we can’t wait to see its first images.

Kimberly Adams: Which are coming this summer, right?

Caitlin Casey: Yeah, yeah. So they’re in the process of turning on each camera right now, which will take over six months to get everything up and running. And so we hope to get those first images early this summer.

Kimberly Adams: Okay, what is I mean, other than the fact that it’s just cool, what is so special about this telescope? And how does it compare to the Hubble Space Telescope, which is the one that most of us have seen already really amazing images from?

Caitlin Casey: Right. So when we talk about the Webb telescope, we often hear this comparison, like, it’s the next Hubble Space Telescope. And it is our closest analogy to the next Hubble Space Telescope, but it is so much more. It is a much larger telescope. It’s about 21 feet across, as opposed to Hubble which is only eight feet across. And the size means that we’re able to see objects that are about 100 times fainter than Hubble can see. And keep in mind that Hubble has seen the faintest things ever recorded by human civilization so far, so it will go that much deeper. And also because it’s a larger telescope, it gives us sharper resolution so even the exquisite detail we see on you know nebulae and distant galaxies in the universe. With Hubble we will see that improve with James Webb Space Telescope.

Kimberly Adams: So what are you and your team working on in particular, once you can sort of tap into what the telescope is seeing?

Caitlin Casey: My team is working on discovering some of the most distant galaxies that have ever been found. And we will find many, many more than Hubble has found because JWST is able to see objects so much deeper. So we’re building what’s called a deep field, which is similar to Hubble Deep Field, if listeners have ever seen that image, it’s an image that represents a series –

Kimberly Adams: Let’s just assume we haven’t.

Caitlin Casey: Okay, yeah, so the Hubble Deep Field is the deepest image ever taken up space. So I really encourage everyone to go look it up online, if you haven’t seen it, it is a very small patch of sky that would otherwise appear totally blank or dark to the naked eye. But it’s a patch of sky that’s roughly the size of a head of a pin, if you’re holding that pin at arm’s length away from you. So a very tiny patch of sky and in that patch of sky, Hubble found thousands of sources of light that are the faintest sources of light we’ve ever seen. We now know them to be galaxies, which are collections of billions of stars stretched out across enormous distances in the cosmos. And they are so far away that the light traveling from these distant galaxies has taken most of the history of our universe to reach us to reach the Hubble Space Telescope. So what we’re doing with JWST is we’re building bigger, better deep fields that will see farther into the past, they will see more exquisite detail, and we’ll be able to understand how the universe itself assembled in just a couple 100 million years after the Big Bang, which represents an era of cosmic dawn, when everything is forming for the first time. And so we’ll be able to see that directly with JWST.

Kimberly Adams:Will we be able to see aliens?

Caitlin Casey: That’s a great question. Sadly, no, we will not be able to see aliens with JWST. You know, but the search continues. The search continues. And it sounds almost, you know, silly, I’m sure to some that, that there are legitimate efforts to search for intelligent life out there. But it is getting to be more and more of a serious search with every passing year. So what we will learn from JWST for understanding aliens, is we will take this step of actually being able to see what’s in the atmospheres of earth-like planets around other stars. So not around our sun, not in our solar system, we will see actual atmospheric composition. Like is there oxygen? Is there water vapor? What’s in the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars? Would those planetary systems be habitable to life? We will get answers to that with JWST.

Kimberly Adams: Can you give a sense of the scale when it comes to the time, the money, the resources, the emotional strain that went into building this telescope?

Caitlin Casey: Oh boy. Yeah. So this telescope represents such a monumental effort, not just for astronomers who love to look at the night sky, but for engineers, for the government, for all of the different players involved. So JWST, you might be aware, has this price tag of $10 billion, which sounds like so much, but it actually is just a drop in the bucket compared to the overall budget for NASA. And also, it should be pointed out it’s a very large international collaboration. So it is a partnership of NASA and the European Space Agency and also the Canadian Space Agency that have pooled resources together to make this telescope happen. It has been in progress for over 20 years. Right when Hubble first got its first images, like the Hubble Deep Field, that was when we started planning for James Webb. I wasn’t planning because I was 10 years old. But I have become aware that, you know, the telescope process started really early on. And so it has had some stumbling blocks along the way, it’s had some delays, because the technology is brand new, and invented for the purpose of making this telescope work. We haven’t had a telescope like JWST before, we can’t just, you know, go to the Telescope’s R US store and say, “Yes, I’ll have that one for $10 billion. Thanks.” You know, we are inventing this thing as we’ve gone along in the process. And so the cost represents the effort of all of the personnel involved, both representing personnel from funded by the government through federal grants, but also through private industry. So there are companies like Northrop Grumman, Ball Aerospace had been really involved in the development of this facility. And then, of course, it’s launched into space, which was so successful on Christmas Day, December 25, of last year, was made possible by Arianespace, which is a French aerospace company that launches packages and payloads on behalf of the European Space Agency. So it really represents the culminating effort of thousands of people around the globe to make a mission like this happen.

Kimberly Adams: Where does this mission sit in sort of the balance of what NASA is doing compared to what private industry is doing in space right now?

Caitlin Casey : For sure, space is a happening place right now. I’m sure folks can appreciate that. There’s been a lot of discussion of crewed spaceflight missions, human spaceflight, over the past year or so with companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic having some of their first, you know, launches into having crewed spaceflight. And NASA, of course, has been the big player in all of this for decades, right in the 1960s, with the Apollo program that invented the field of spaceflight in the US. And so it has been a major part of NASA’s portfolio, it represents roughly half of NASA’s budget dedicated to human spaceflight. But programs like this telescope, JWST, are not a part of that at all right? It is completely robotic. It is a part of NASA’s science portfolio, which is roughly only a third of its entire budget. So I think in the future, we’re gonna see a continued diverse portfolio for NASA, in terms of the what it covers in terms of human spaceflight. But the theme going forward certainly is lots of private-public partnerships, where SpaceX is involved in sending humans to the ISS, you know, so we’re gonna see more of that for sure.

Kimberly Adams: For as long as the ISS lasts.

Caitlin Casey: Right. Right. Yeah. So I mean, but in terms of, you know, my perspective, as an astronomer, and, you know, a user of telescopes, that human spaceflight arm of NASA, it operates totally independently. The budget for telescopes for understanding our own universe that is really, you know, segregated off in a different corner of NASA’s budget. And you know, the two, rarely mix.

Kimberly Adams: You know, it feels like NASA is still involved in human spaceflight. But the commercial sector is not so much. You have NASA with the James Webb Space Telescope and looking out into the galaxies, but the commercial sector is really focused on commercial satellites and space tourism and those sorts of things, even with these public-private partnerships, do you see the commercial space industry as moving into the hard sciences at any point?

Caitlin Casey: That’s a great question. I think you’re right, that it has been really quiet in terms of discussions of private investment in space, astrophysics, you know, the hard science. But there is some crossover, and some of it is actually not all good. So you are probably aware that there are these groups of satellites being launched into space called constellation satellites, that will do great things, like, for example, bringing high speed internet to every corner of the globe. But they also have –

Kimberly Adams:This is the Starlink, yeah?

Caitlin Casey: This is the Starlink project. Yeah. But there are other constellation satellites, as well, you know, other than Starlink. But Starlink has this noble goal of bringing high speed internet to every corner of the globe. But there are also some drawbacks that haven’t really been discussed in an organized way. It’s not regulated by the government very much. For example, constellation satellites, will have significant negative impact on the operation of telescopes on the ground, they basically look like little, little streaks across the sky, you can see them actually at nighttime, pass overhead. And they make it very difficult to operate telescopes that are not in space, but that are on the ground, which represent kind of a big fraction of how we learn about the universe. And there’s also some concern that constellation satellites will increase space debris and create a non- negligible hazard to spacecraft that want to go up and, you know, pass through this field minefield of material and satellites that have been launched into space. And so there is, you know, some discussion that potentially, that’s harmful to you know, the broader, you know, not just when we look up in the night sky, will we even see stars anymore, but also the concern of whether or not we will be able to avoid space debris and future launches. So that’s one.

Kimberly Adams: But isn’t that happening now?

Caitlin Casey: Yeah, it’s happening now. And it’s largely happening in a way that’s not highly regulated, you know, kind of space is our new Wild West. And so, you know, there aren’t a lot of regulations on who can launch what? And so yes, it’s happening. And I think we might be in a point a couple years from now, where we we should probably evaluate if everything that has been launched was a good idea. I mean, there are some mitigation strategies that companies like SpaceX, you know, they, they certainly hear the concerns of the community and they’re trying to address them. It is not entirely clear that given the vast number of satellite launched into space, that we will have, you know, this under our control in five to 10 years time, but it would be great though, on the flip side to also see private companies show interest in in supporting telescope development. Going forward in the future, it should be pointed out that Hubble Space Telescope and developing the technology for James Webb Space Telescope, that has led to significant technological development and spin offs that significantly enhance other industries, like medical equipment, eye surgery, use of lasers, optics, precision sensors that are used in airplanes, GPS. A lot of these industries have come about because of the technological developments made by telescopes, and, you know, just trying to get the best telescopes off the ground. And so I do see significant room for huge technological strides if we’re able to able to form more partnerships and get more projects off the ground.

Kimberly Adams: Okay, I could talk about this for ages, but I’m going to let you go. That is Caitlin Casey, professor of astronomy at the University of Texas at Austin, who is going to be using the James Webb Space Telescope once it’s fully up and running. So happy stargazing.

Caitlin Casey: Thank you so much. Can’t wait to see those images.

Kimberly Adams: So tell us what you think our number is 508-827-6278 also known as 508-82-SMART or leave us a voice memo at makemesmart@marketplace.org with what you’re excited about seeing from the James Webb Space Telescope and we will be right back with Kai.

Kai Ryssdal: Is that the right sting?

Kimberly Adams: That is the right sting! It has been a while.

Kai Ryssdal: Fire me. Oh my lordy be.

Kimberly Adams: Public radio can’t lose any more people Kai.

Kai Ryssdal: Shhh! Kimberly! Don’t say that out loud. Oh my goodness. Okay, so let us just proceed, shall we? Cause obviously I’m back on the pod now. Miracle of podcasting.

Kimberly Adams: Yes, it’s magic. It is the magic of not radio. Yes, podcasting. But audio magic. And it’s time for the news fix. So Kai, since everybody’s been hearing my voice, let’s start with yours.

Kai Ryssdal: Oh, my goodness. Alright, so mine is prompted by two things. One is reality. And the other one is a note that we got from our corporate overlords in St. Paul at the American Public Media Group saying to nobody’s surprise, oh, look, we’re pushing back the date for our voluntary return to office. And I just, I think we need to get this out on the table that this, you know, we’ve been – well, that’s not true. Not all of us. But some people have been eager to get back to the office, there’s a certain camaraderie blah, blah, blah, yes, schedules can be more flexible now. And we’ve all learned things in the pandemic, but, you know, a lot of people have been looking forward to getting back to the office in some way, shape, or form. And I think we just need to acknowledge that that is not going to happen for a good long while because not only is Omicron here, but whatever the next variant is, is going to be here, and we’re going to be muddling through. And I think everybody just needs to get ready for for it not to be happening. And and my you know, news peg, if you will, if we need this other than what APMG says, is this piece in the journal today saying other companies, lots of other companies are saying, You know what, we’re not going to predict this anymore. We’re just gonna say “You get back to the office when you get back to the office, but it ain’t gonna be now” and that includes Marketplace. So that’s that. Number two and more substantively: Electric cars, they are really, really hard to build. Well, no –

Kimberly Adams: Wait, wait.

Kai Ryssdal: I’ll tell you how I got here. Well, okay. What, you want to know how I made that turn?

Kimberly Adams: I would say that the pandemic is also very substantive …

Kai Ryssdal: Well, no, ok, that’s true. You’re right. You know what, that’s a really good point. Because I think a lot of us have now internalized that so much and it has faded to, in some degree to background noise. Like you’re like, okay, yeah, of course, we’re all gonna go late back to the office or whatever, I don’t even know. Okay, so, electric cars. We really want to get one in this house. We want to get a couple of them because we got a couple of drivers. And we’ve got our eyes open and my wife has decided she really likes the Rivians, I really hate the way they look. But she gets to decide how we spend our money. So we might get one, I don’t know. But here’s the point, electric cars for all the glory that Tesla gets, and for all the press that Elon Musk gets, and for as fun as Tesla’s are to drive, and yes, there’s a bunch of other less expensive models, they are really hard to build cars are really, really, really hard to build and sell, right? I mean, the big car companies sell like 8 million cars a year, and Tesla sells a minuscule fraction of that. And now there’s another company called Rivian, which just yesterday announced, oh, my goodness, we’re not going to make our production targets and an executive is leaving. They do say the executive is leaving because of a long scheduled retirement, but the production problems are the real thing. And if you remember, Tesla had them too and still does to some degree have them. And I just think before we all start banking on you know, everybody have an electric cars, we need to acknowledge that the internal combustion engine side of that business had a 90, maybe 110 year headstart. And and it ain’t gonna be all that soon that we’re all gonna have electric cars, even though we might want them. And that’s it. That’s my spiel.

Kimberly Adams: Ah, I don’t know Kai. We talked over on Marketplace Tech to one of the editors from CNET who’d been covering CES, the Consumer Electronics Show this year, which has basically become an auto show. And everybody and their mother has an electric vehicle. And he was saying that people are going to look back at 2022 as the year that electric cars really went mainstream. And they’re looking at this Chevy Silverado electric pickup truck.

Kai Ryssdal: The trucks, sure.

Kimberly Adams: The trucks! And even Sony has an electric car. And he’s actually predicting kind of the opposite. Like, yes, it’s hard to make, but everyone is getting into it, that the speed of adoption and advancement is about to really ramp up. So I mean, we’re in the sort of start-up phase –

Kai Ryssdal: No look, I totally, I totally hope he’s right. Yes. Go ahead.

Kimberly Adams: Yeah. Well, I mean, on the startup side of things, I definitely can see like, yeah, that’s gonna be, it’s really hard to go from zero to electric car in like, a couple of years.

Kai Ryssdal: Ha, zero to electric car.

Kimberly Adams: But the sort of established – ha ha ha, that’s funny. I didn’t realize I did that.

Kai Ryssdal: No, that’s good.

Kimberly Adams: Thanks. It was an accident. But, you know, the –

Kai Ryssdal: Yeah.

Kimberly Adams: Companies with established assembly lines, I think they may have a little bit easier of a time of it. But that’s all.

Kai Ryssdal: I think that’s a fair point. That’s a fair point. No, but I mean, you know, you’re an observer and a consumer of news.

Kimberly Adams: I’m an observer, I ride in cars. And there is – there’s the ship horn.

Kai Ryssdal: That’s all good. It’s all good. A little verisimilitude.You know, I mean, I’m in my shed this morning. So you know, there could be dogs barking anytime. So let’s get on with it.

Kimberly Adams: I removed the bell from my cat before we started, because, without fail, this is the moment when he would decide to actively play. Okay, so I’ll go on to my news fix, which is less fun, but so important.

Kai Ryssdal: No, but it’s amazing, it’s amazing.

Kimberly Adams: The Washington Post has this amazing in-depth investigation. I think it took the reporter more than a year to do this. But it’s detailed, it’s long. And they had a look of all the people who have who ever served in the US Congress, who owned human beings that actually enslaved people. And there were more than 1700 people who served in the US Congress and reading straight from the peace in the 18th, 19th and even 20th centuries, who at one point or another, owned people. And what’s super fascinating about this is it digs into how that impacted policy. Because, you know, even today, we talk about how much where a member of Congress comes from and their upbringing, how it affects how they, you know, pursue policy, how they investigate things and the type of legislation that they support. And so if you think about that many people who ran our country that owned other people, of course, it would shape policy. And this is particularly fascinating coming at this time, when there’s such a national debate over how we learn our own history and how we teach our own history, and schools all over the country, you know, in battles with state legislatures or their or school boards or even parents about what they can and cannot say about the history of our country. And, you know, it’s it’s important that we know I learned so much from this investigation. I really did. It’s really good. I can’t recommend it enough.

Kai Ryssdal: It’s amazing. It’s ongoing. In fact, I think they have asked for public help and you know, they found the 1700. But there are certainly more that are not yet documented. And they asked for public help finding this and I think it’s gonna be really interesting to see, you know who else is on this list? It’s craziness that it hadn’t been actually examined before, you know, it’s kind of wild. And these weren’t just southern members of Congress from the air quotes “slaveholding states,” you know, these people were from all over. I mean, I’m not gonna do it justice. So I just, you know, it’s gonna be on the show page. It’s really, really good. Yep, yep. Yep. Check it out.

Kimberly Adams: Okay. Uh, yeah, I guess we should move on to the mailbag. Let us do that. Hey, make me smart teen it’s Brianna from Phoenix. I’ve been from Brooklyn, New York longtime listener. First time voicemail, I want to discuss a slightly different but maybe related thing. Okay, on Twitter @MJ Graves from Houston tweeted us about Lake Superior University’s list of banished words from 2022. And included in the list is “deep dive,” which is obviously as per today, a very well-used term here on Tuesdays. And I should acknowledge here much to the chagrin of the folks on Discord who have pointed out to me on numerous occasions that they feel we do not go deep enough into our deep dives. And so they are asking that we stop using that term. I should also say that on the list is “supply chain,” which I don’t really know how to feel.

Kai Ryssdal: What are we gonna, what are we gonna, what are we gonna do? What?

Kimberly Adams: I think I looked at the website and what they’re talking about is how everyone blames every single shortage and every single problem in the economy right now supply chain, so I get that but we’re talking about the supply chain. Also “new normal” 100% agree that needs to go because ugh. “You’re on mute.”

Kai Ryssdal: How are you supposed to tell people? You got to tell people. Hold up a big L on your forehead go “loser, loser!”

Kimberly Adams: I dare you in the next meeting, I will laugh so hard.

Kai Ryssdal: Only one of its with our corporate overlords. How about that? All right.

Kimberly Adams: Stop it Kai!

Kai Ryssdal: Too many people leaving public radio already. Anyway.

Kimberly Adams: And at the top of the list is one of your favorites.

Kai Ryssdal: I know. I know.

Kimberly Adams: I see you put it on Twitter all the time. “Wait, what?” Are you gonna drop that?

Kai Ryssdal: It’s so good! You’re like, “wait, what?” No, I’m not gonna drop it. I have the courage of my convictions Miss Adams. The courage of my convictions.

Kimberly Adams: Yes, you do you Kai Ryssdal.

Kai Ryssdal: I will do me. All y’all could do all y’all. I mean, you know, tell us what you like, don’t like about words that we use on this podcast. We’ll consider adding them to our banish list or not. I don’t know, makemesmart@marketplace.org. You know how to get a hold of us. Okay, so before we went over for the holidays, we asked you about your travel plans if you had any, where you wanted to go. Here is one of the replies we got.

Ryan: Hey, make me smart friends. This is Ryan from Rochester, New York, home of Eastman Kodak home of Xerox and home of the culinary masterpiece known as the garbage plate. Look that up sometime. Wanted to say my wife and I just a few weeks ago book a trip to Portugal. However, about 10 days after we booked that trip, which is going to be like the end of March, we all had to start learning how to pronounce Omicron. Turns out that Portugal is actually maybe the most vaccinated country in the world. Something like 90% or close to it of people are vaccinated there. So we’re like cautiously optimistic, but still a little nervous that we’re going to have a second vacation that has been canceled by this pandemic. Anyway, thanks for making me smarter.

Kimberly Adams: Oh, I hope not good luck.

Kai Ryssdal: Yeah. Yeah.

Kimberly Adams: I wish everyone’s vacations to go well. Yeah, yeah. You going anywhere?

Kai Ryssdal: No, no hanging around. What can I do?

Kimberly Adams :My family has yet another cruise planned, Kai.

Kai Ryssdal: No way. Kimberly! Tell your mother to stop doing that.

Kimberly Adams: This one wasn’t my mother. It’s my sister.

Kai Ryssdal: What is it with your family? Let’s go. Are you kidding me? I honestly I can’t. I can’t, I can’t even believe it.

Kimberly Adams: Okay, anyway, we’re gonna leave you with today’s answer to the make me smart question, which is: “What is something you thought you knew you later found out you were wrong abou?” This week’s answer, It comes from Adam Riess. He’s a professor of astronomy at Johns Hopkins University and one of the winners of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics and I interviewed him recently on Marketplace Tech about, you know, of course, the James Webb Space Telescope because of course, I’m a nerd. And I love it.

Adam Riess: Well, to be honest with you, the first thing that jumps into my mind is that the ability to make progress in many fields, I used to think just dependent on how smart you were. And what I learned over time is more often how maybe determined you are. How much sort of grit that you have. That you know it’s not all inspiration. A lot of it is the perspiration.

Kimberly Adams: Amen.

Kai Ryssdal: Yeah, I totally buy that. I totally, buy it. You got to put in the work. You got to do the work.

Kimberly Adams: Yes, it’s about drive. It’s about power. Anyway. Don’t forget to send us your answer.

Kai Ryssdal: What are you really trying to tell us Kimberly?

Kimberly Adams :No, I mean, I’ve been spending too much time watching Tik Toks and Instagram reels lately but that’s that’s a whole other thing. Okay. Don’t forget to send us your answer to the make me smart question. You can consider calling us and leaving us a voice message on our number 508-82-SMART we really appreciate it and “Make Me Smart” will be back tomorrow. God willing and the creek don’t rise.

Kai Ryssdal: There you go. I love that saying. For reasons I don’t even know “Make Me Smart” is directed and produced by Marissa Cabrera. Our team also includes producer Marque Green, Tony Wagner writing our newsletters. Also welcome to our new intern Tiffany Bui. Yay, new interns.

Kimberly Adams: Today’s program was engineered by Charlton Thorp and Drew Jostad, with mixing by Emma Erdbrink. Ben Tolliday and Daniel Ramirez composed our theme music. The senior producer is Bridget Bodnar. Donna Tam is the director of On Demand and marketplaces vice president and general manager is Neil Scarborough.

Kai Ryssdal: Excellent.

Kimberly Adams: We beat the amalgamation podcast for the win.

Kai Ryssdal: Yes, yes.

None of us is as smart as all of us.

No matter how bananapants your day is, “Make Me Smart” is here to help you through it all— 5 days a week.

It’s never just a one-way conversation. Your questions, reactions, and donations are a vital part of the show. And we’re grateful for every single one.