After last week’s dense, math-heavy lesson, we’re taking it a bit easier.

Chapter 9 is about the credit market, and it brings together, in a new context, a lot of the fundamentals we’ve already covered.

If you aren’t enrolled yet, sign up here to get all these lessons emailed to you!

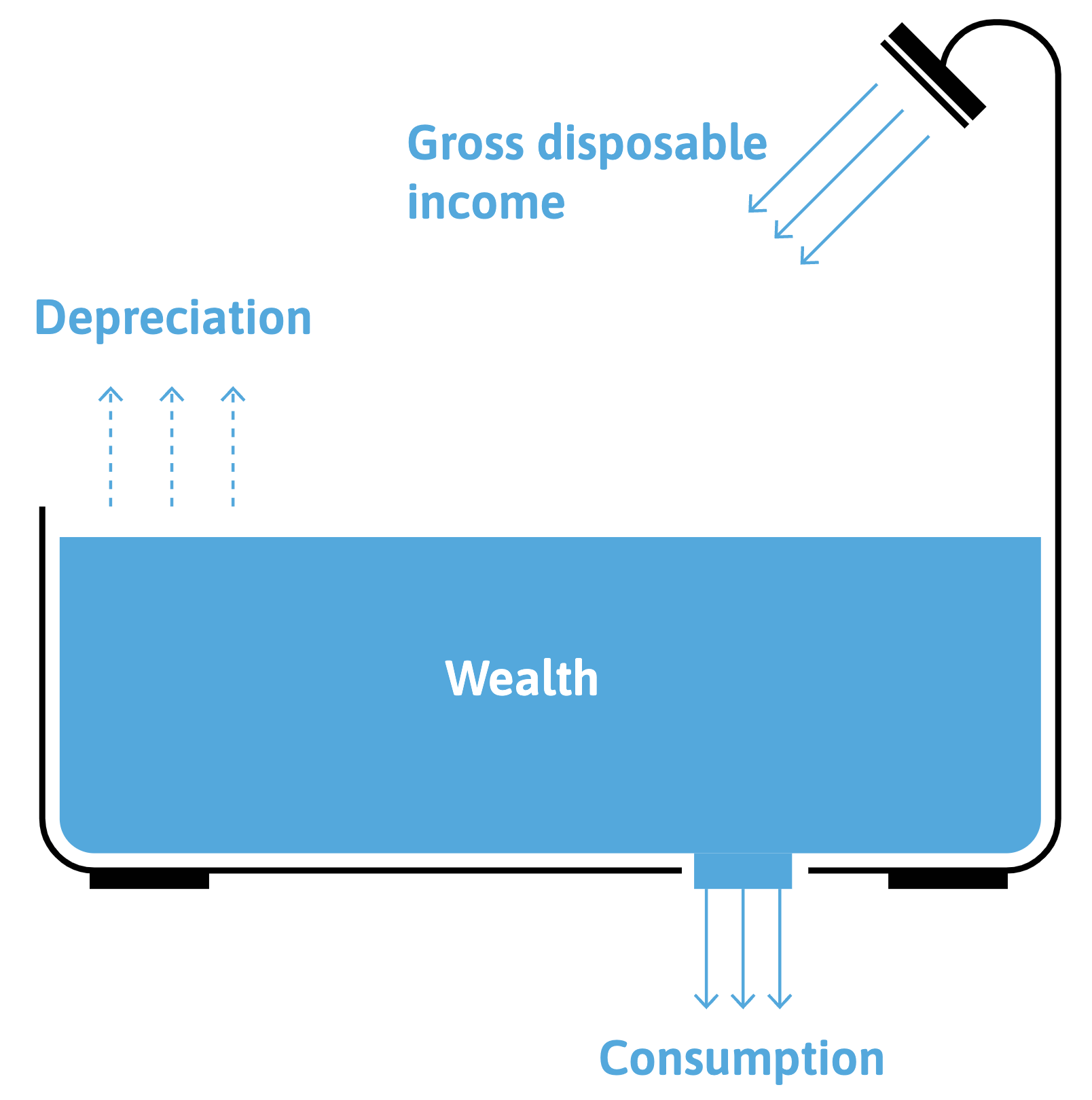

To start budgeting like an economist, picture a bathtub.

The water coming in from the tap is your income (after taxes), and everything the tub holds is your wealth, including money in the bank and major assets like a car or home. The water that evaporates is depreciation, like your car losing value as you put miles on it. Wealth that is consumed on wants and needs goes down the drain, so to speak. If your budget were tied just to water in the bathtub, or existing wealth, you’d be restricted to spend only what you already have.

Borrowing, lending, investing and saving allow people to “rearrange the timing of their spending.” For example, we might take out a loan or charge some items on a credit card today based on the expectation that we’ll have a higher income later, enough to both pay back that debt and fund future expenses.

But borrowing isn’t free. Lenders charge interest, which, the book notes, “raises the price of bringing buying power forward .”

The credit market involves the trade-off between money spent now versus money spent later. This is an exchange, similar to others we’ve discussed, like hours of work versus free time (Chapter 4). In the credit market, the marginal rate of substitution involves the trade-off between money spent now versus money spent later. But rather than hours of work versus free time, or bread supplies versus their price, our marginal rate of substitution follows money spent now versus later.

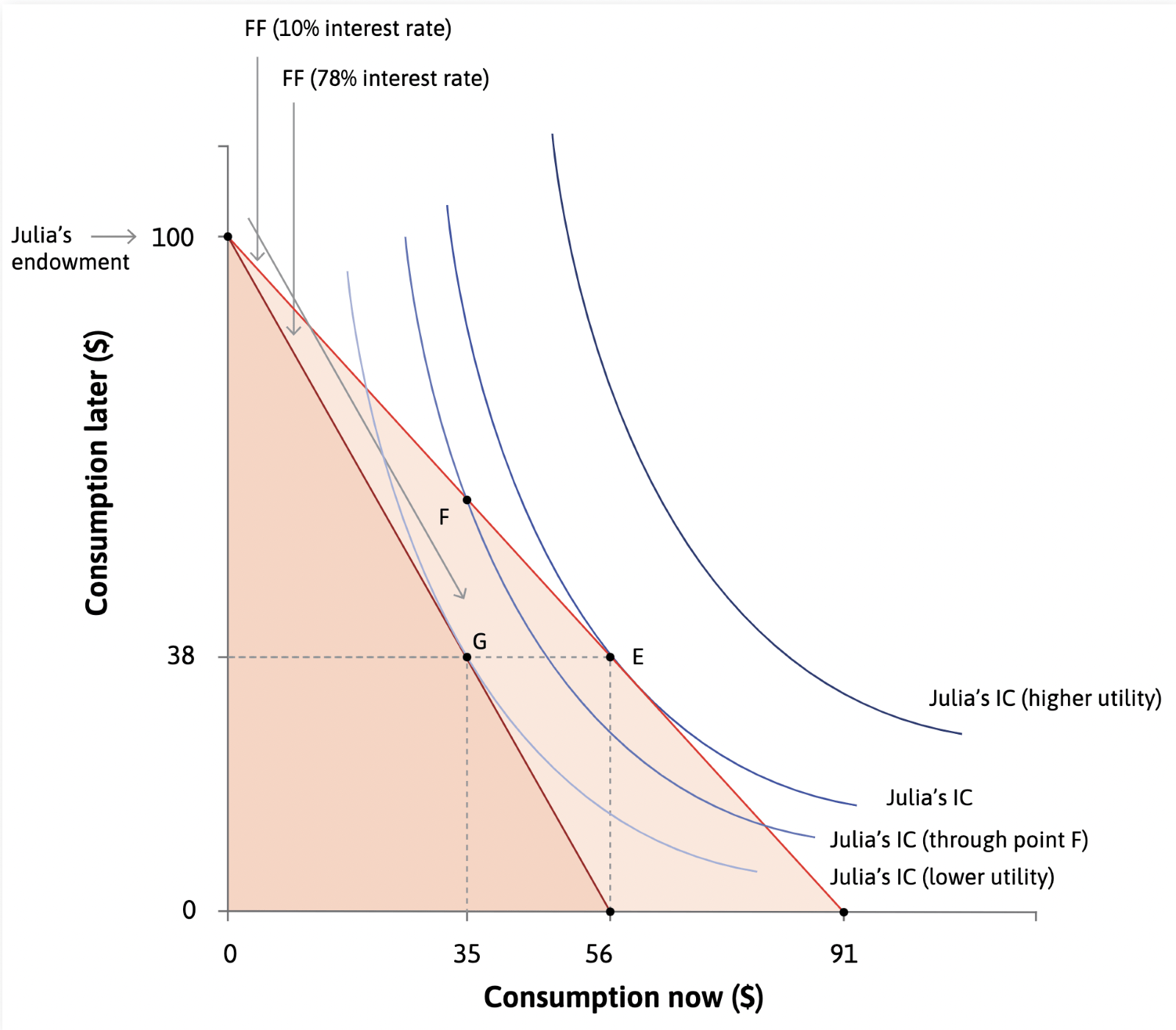

👇 You can see how this plays out in Julia’s situation from the book.

Julia will receive $100 later but needs some money now. At a 10% interest rate, she can borrow $91 to spend now and repay plus interest later. The line connecting these points is shaded, showing all the feasible combinations of borrowing and repaying. The line becomes steeper, and the shaded area smaller, when the interest rate increases to 78%.

We can look at a different version of this chart from the perspective of Marco, a lender. If Marco charges a higher interest rate, he’ll end up benefiting more than Julia. Like we’ve seen throughout the course, just because an exchange is mutually beneficial doesn’t mean it’s fair.

What if Julia can’t repay Marco? Just as employers might take measures to ensure employee productivity, the book points out that Marco might mitigate his risk by setting a higher interest rate or asking for collateral. Julia might put up her home or some other equity that Marco could claim if she didn’t pay him back.

People who start with more wealth tend to have better access to credit, with more favorable terms. In this way, the credit market can also perpetuate inequality. As the textbook puts it: “Rich people lend on terms that make them rich, while poor people borrow on terms that make them poor.”

Nominal interest rate: The agreed-upon interest a borrower pays a lender. Taking the inflation rate into account will determine the real interest rate the borrower ends up paying with their increased spending power.

Credit rationing: The mechanism through which borrowing perpetuates inequality. People with less wealth may get more utility from moving smaller amounts of spending back in time, but can’t afford to put up as much collateral or equity.

We spent a lot of time this week talking about borrowing, lending and investing among individuals. But it’s important to draw a line between household debt and the debt ceiling that U.S. lawmakers fight about every couple of years.

U.S. national debt passed $35 trillion in 2024. When it hit $31.4 trillion in a year earlier, some hard-line Republicans threatened to let the country default unless the administration agreed to substantial budget cuts.

“What I really think we should do is treat this like we would treat our own household,” then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said on Fox News. “If you had a child, you gave him a credit card, and they kept hitting the limit, you wouldn’t just keep increasing it.”

But economists call this comparison inappropriate. The sheer scale of the government, not to mention its ability to collect taxes, make the dynamics at play very different from even a wealthy household. Plus, credit card limits are set by lenders to manage their risk. The federal debt limit is set by Congress, not creditors, and emerged from the changing relationship between branches of government during the First World War. Read our history of the debt ceiling here.

In Chapter 10, we’ll learn about why banks believe they’ll be rescued from their own bad choices.

Econ 101 is a production of Marketplace, a listener-supported public journalism outlet. Consider making a donation to support our mission to make people smarter about the economy, tech and the world. Your donation today makes for a better Marketplace tomorrow.

This course was written and edited by Ellen Rolfes, Erica Phillips, Tony Wagner and David Brancaccio. It was originally published in February 2023 and updated in November 2024.

Revisit previous lessons:

Chapter 1: The relationship between capitalism and income inequality

Chapter 2: Game theory and rational decision making

Chapter 3: How policymakers and economists assess fairness and efficiency

Chapter 4: Finding balance between work and leisure (like an economist)

Chapter 5: What is an “economic rent” and how does it influence working conditions?

Chapter 6: Why companies often pay workers more than minimum wage

Chapter 7: A primer on supply and demand, and how firms maximize profits

Chapter 8: How competition impacts consumer prices and worker wages