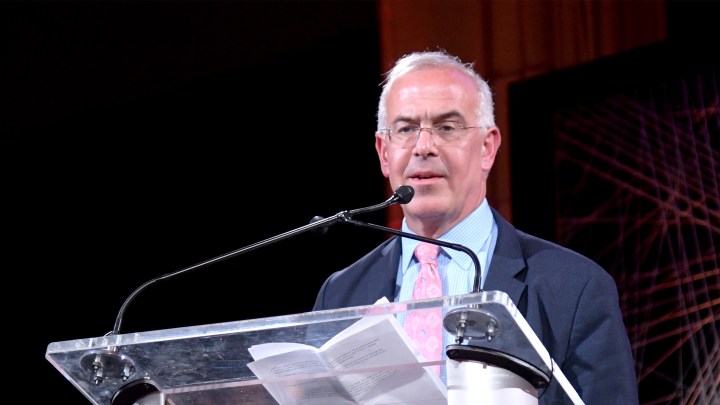

David Brooks on what’s responsible for America’s class divisions

David Brooks on what’s responsible for America’s class divisions

Over 20 years ago, political commentator David Brooks wrote “Bobos in Paradise,” a book about America’s “creative class” of politically progressive knowledge workers — a class that championed openness in most senses of the word, and that he assumed was open to anyone if they wanted to join.

But two decades later, revisiting the topic for The Atlantic, Brooks says that thinking was naïve – as he’s seen the country’s cultural elite concentrate their economic and social power, and take steps to ensure their children follow in their footsteps.

“We have not made the society more equal, we’ve made it more unequal. And not only is there a class division around education, there’s this income division as we concentrate in the really affluent cities. And then there’s a status and social inequality,” he said in an interview with Marketplace’s Andy Uhler. “Before long, we had formed an elite Brahmin class that was driving the rest of the country crazy.”

The following are edited highlights from their conversation.

Who are the bobos?

Andy Uhler: In the article, you reexamine this group of people that you wrote about back in 2000 in the book “Bobos in Paradise” — you call it the creative class. Give us the idea of what a bobo is.

David Brooks: A bobo is a bourgeois bohemian, so those are people with ’60s values and ’90s money. They were people like Steve Jobs who wanted to be a big corporate executive, but wanted to wear black t-shirts. And so those are people who made money because they were really good with ideas and words. But they didn’t want to be corporate sellouts, so they had to devise a whole new consumptuary style of spending their money. So they created a style where spending money on a chandelier would be vulgar, but $20,000 for an AGA stove just showed you a foodie, and that was good.

Uhler: You wrote about this 20 years ago, and then you decided to revisit the concept now. What spurred the idea of, “You know what, I need to sort of rethink [this]” — because you admitted that some of the stuff that you wrote 20 years ago isn’t the case these days, right?

Brooks: Yeah, I thought it was sort of a cool class to be a part of, which I was. … 20 years on, the people who made money by trading ideas: First of all, we all moved to big cities like Denver and Chicago and San Francisco. Second, we concentrated power and married each other. Third, we invested huge amounts of money in our kids, so they came to dominate the competitive schools that produced us. And so, before long, we had formed an elite Brahmin class that was driving the rest of the country crazy.

Uhler: Throughout the piece, you talk about the bobos, but you use the pronoun “we” — you include yourself in this group. And I’m probably a part of this group too. I’m curious, was there a moment where you understood, “I’m talking in the ‘we’ form here”?

Brooks: It’s pretty hard to ignore. My parents were college professors. I went to the University of Chicago; grew up in suburban Philadelphia and New York City. I’ve been working for 20 years at The New York Times. So when you fit a stereotype as well as I do, you gotta confess to it.

“At first, going to GPAs and SATs — that was an attempt to democratize education. And it worked for a golden generation. …Then it just became a way to lock in your advantages as affluent families.”

How the education system perpetuates class divisions

Uhler: One of the points you made 20 years ago was that, theoretically, you could join this creative class if you had the right degree, if you had the right job, things like that. Is this not true anymore?

Brooks: That’s not true. The top 60 schools, some of them have more people from the top 1% of earners than from the bottom 60%. Upper middle-class college educated folks invest, for example, $5,000 per kid just in extracurricular activities — so their kids just have huge advantages when it comes to applying to these schools. And so we have not made the society more equal, we’ve made it more unequal. And not only is there a class division around education, there’s this income division as we concentrate in the really affluent cities. And then there’s a status and social inequality. So people in the media and the academy and the big nonprofits — if you’re not seeing by us, you feel unseen by society; you feel like you’re in flyover country; you feel neglected. And hence, we have Trump. And if you tell people they’re invisible, they’re going to react really badly. And I should say, not just the U.S. In every Western country, this has happened.

Uhler: It sounds like what you’re telling me is that education plays a big role in perpetuating this sort of class structure that we have today.

Brooks: Yeah, basically the SATs [became important] because people at Harvard in the 1950s decided, “We can’t just be Ivy League schools for a bunch of blue blood males, we have to diversify.” And so, at first, going to GPAs and SATs — that was an attempt to democratize education. And it worked for a golden generation. And then it stopped working. Then it just became a way to lock in your advantages as affluent families. It’s just crazy, frankly, that we divide young people on the basis of how they do in high school tests and SAT scores between the ages of 15 and 25. It’s just crazy that the skills that make you [a] good McKinsey consultant are more valued than the skills that make you a good home health nurse. And so I would say the criteria of our meritocracy — nobody would devise that criteria now. We, hopefully, have a much broader view of what constitutes human excellence and the diversity of human people. But we settled on this narrow criteria, and now we’re kind of stuck with it because of the U.S. News & World Report rankings.

The bobos’ economic “stranglehold”

Uhler: You write that the bobos have this stranglehold on the economy. Explain what you mean by that.

Brooks: One of the things we’ve done is we’ve congregated in cities. It used to be companies, you know, Lowe’s hardware had headquarters in Wilkes, North Carolina. And the banks — you had your local bank in your mid-size Tennessee city. But as corporations have concentrated in cities, you get this concentration of wealth. And this happens in the U.S., but pretty much every Western country. And so other places naturally feel left out. And so the parties who represent the more rural parts of these Western countries, they say, “See? They’ve concentrated the wealth, they’ve built up social status, they hate us, and let’s go on the assault.” And that, I think, is a large part of Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán, Boris Johnson, Marine Le Pen, etc., etc.

“It’s just crazy that the skills that make you [a] good McKinsey consultant are more valued than the skills that make you a good home health nurse.”

Uhler: It sounded like, in the article, you were giving at least a little bit of praise to the Biden agenda. Is there something that can be done in Washington to reduce just how insular this elite class is?

Brooks: I’m hopeful. Joe Biden is a unique creature in that he did not come from the creative class. He’s the first president since Ronald Reagan who does not have an Ivy League degree. Condescension is alien to his nature, his home is Scranton. And so he really is more formed by working-class community than by the educational system. And so, just as a cultural signal, I think he sends an egalitarian message. Second, the Biden agenda: If the last 40 years have been a giant funnel directing money to highly educated people in the cities, it seems to me the Biden agenda is a giant funnel directing money away from the cities, toward less educated people all around the country of all races and varieties. And so I’ve generally been on the right in this country, but given the circumstances of widening social and economic inequality, I think shifting large amounts of money — through a child tax credit, through education vouchers, through infrastructure jobs — that A) may ease some of the inequality, and B) is just a sign of respect that, “We’ve seen what’s happened to you over the last 40 years, and we’re going to try to do something about it.”

Where we go from here

Uhler: Now, this is not all that positive of a portrait that you’re painting in this article. You’re worried about what you see. Where do we go from here? What do you think?

Brooks: I do think some sort of economic redistribution is part of it. But the second thing … it’s contact. There’s a guy named Gordon Allport who had a theory, contact theory, that if you bring people together, and they actually get to know one another, then a lot of the stereotypes, a lot of bitterness, will fall away. A lot of people vastly overestimate how much the people on the other side hate them. There’s an industry of people whose job it is to exaggerate how much people on the other side hate them. And once you actually make contact, then a lot of that fades away. And I think we all go home, and we all have members of our family who are on the other side of the political divide — somehow hammering through that is an essential cultural task, aside from all the economic and political things that have to happen.

“We’re all fumbling toward versions of community, so we can feel belonging again. And that’s a messy process, but I’m hopeful that we get through it, the way we have previous times in American history.”

Uhler: You’re talking about a sort of class warfare. How does it end? Or does it end? I mean, is that what you’re sort of hopeful about?

Brooks: Yeah, well, we could have a civil war and crack up, but I’m hoping that’s not the case. I think we’ve gone through, in this country, moments of moral convulsion: when people were disgusted with establishment power, and when new moral crusades came on the scene; a new generation demanding changes. I think we’re in the middle of that right now. But, you know, we were in one of those moral convulsions in the 1960s. We were in [one] in the 1890s, the progressive era. We were in [one] in the 1830s with Jackson. So we get through them, but culture changes. It becomes a very different culture. And I think what’s happening in America [is] we had 60 years of hyper-individualism [that] left a lot of people behind; left a lot of people feeling lonely; left a lot of people feeling unseen. And now we’re having an argument about: what kind of group, what sort of communities do we want to be? And there are different versions of what community should look like. But we’re all fumbling toward versions of community, so we can feel belonging again. And that’s a messy process, but I’m hopeful that we get through it, the way we have previous times in American history.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.