The Enron scandal: 20 years later, what’s changed?

The Enron scandal: 20 years later, what’s changed?

It was 20 years ago next month that energy giant Enron — then the seventh-largest company in the U.S. — crumbled, resulting in historic layoffs and ravaging retirement savings accounts.

The scandal led to the indictment of several of the company’s executives and the downfall of its accounting firm, Arthur Andersen. Enron’s demise also spurred the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which tightened auditing and financial regulations for corporations. But two decades and many corporate scandals later — from the many associated with the 2008 financial crisis to, more recently, the collapse of blood-testing company Theranos — some worry that tough crackdowns on white-collar crime may be a relic of the past.

“You’d like to believe that, when something goes wrong, the people who did bad things would pay the price for it, but I don’t think that’s the way it works,” said Bethany McLean, a financial reporter who covered Enron for Fortune and co-author with Peter Elkind of “The Smartest Guys in the Room: The Amazing Rise and Scandalous Fall of Enron.”

“I think the line between what happened at Enron and what happened in the global financial crisis is much blurrier than people might think. Both were examples of lots of people manipulating the rules and figuring out how to make money for themselves out of something that was pretty much destined to collapse and leave economic wreckage for a lot of others in their wake,” McLean said in an interview with Marketplace’s David Brancaccio.

McLean spoke with Brancaccio about the legacy of the Enron scandal, and about why she started looking into the company’s financials long before the fraud became public. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Bethany McLean: I’d already started to become a little cynical about the Wall Street promotion machine — how so many people can make so much money even from a company that is going to eventually fail. So it began for me when a hedge fund manager I’d gotten to know named Jim Chanos said to me: “Have you taken a look at Enron? Because we can’t figure out how it makes money.” And before I worked at Fortune I had worked as an analyst at Goldman Sachs, so I understood how to go through a company’s financial statements — and there was just a lot of weird stuff. But I didn’t write in that original article about Enron’s off-balance-sheet partnerships because, while I was cynical in some ways, I thought, “These have been signed off on by the board of directors, by the accountants, by the lawyers. And it looks weird to me, but I guess I must just not be sophisticated enough about these things.” So Enron was a wake-up call to me about how compromised all parts of the system could be.

What enabled Enron

David Brancaccio: That’s probably one of the central lessons of the Enron story. There was a whole ecosystem in which it operated that allowed these kind of shenanigans to continue.

McLean: There really was. It took the cooperation of all parts of the system — from Enron’s accounting firm, Arthur Andersen, to its lawyers, to all the Wall Street banks who provided the money that financed these off-balance-sheet partnerships. So many people knew that something was going on, but they were making too much money to speak up about it, or put a stop to it.

Brancaccio: It was a plan that was executed with great skill. But really, when you think about it, the Enron plan was also that its stock would never hit a bad patch. And that’s not a good plan.

McLean: You’re absolutely right. But Enron had figured out how to manipulate the system by using these accounting artifices to always meet or beat analysts’ expectations for its earnings. And that was, essentially, a recipe for having their stock price always go up — because, as long as they made money, and as long as they seemed to make more money than analysts were expecting them to make, everybody said “Check mark, all good.” So basically, Enron thought that it had figured out how to prevent its stock price from ever going down. And that, of course, is a form of arrogance that may work for a period of time, but usually hits a wall at some point.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act

Brancaccio: You did have the Sarbanes-Oxley Act — the legislation that became law after Enron and changed Wall Street, at least for a time. But you’ve thought about this a lot. These too-clever-by-half “smartest folks in the room” — I mean, they [aren’t] at Enron any longer, but they’re at other companies — they’re paid to come up with ways around any new rules.

McLean: Essentially, that’s right. Sarbanes-Oxley was signed by President Bush, and the speech he gave when he signed the legislation in 2002 in the Rose Garden is remarkably similar to the language that President Obama used signing Dodd Frank into law — that this legislation is going to protect small investors, you no longer have to worry that Wall Street is scamming you, we’ve made that impossible. And when you compare the text of the two speeches, it’s really quite upsetting, because it just makes it clear that where there’s a will, there’s a way, and where there’s money to be made, people will find ways to manipulate the existing rules. One of the core lessons from Enron is that a lot of what the company did wasn’t actually illegal. It was a very difficult prosecution for that reason. What Enron really excelled in was using the existing rules and regulations as a roadmap of the possible. And I’ve described it as a “legal fraud,” because so much of what they did was actually legal, even though it created this edifice where the financial statements had no bearing on economic reality. And you see that play out time and time again. It was apparent in the financial crisis of 2008, and there’s been no shortage of corporate scandals since then.

Modern parallels: Theranos

Brancaccio: Do you see possible parallels with the blood-testing machine company Theranos? Allegations are Theranos was also fake-it-till-you-make-it, and maybe fake-it-till-you-make-it works for lots of companies. But we don’t get these scandals unless it all goes wrong.

McLean: The interesting thing, to me, is what you hit on: What is the line between a visionary and a fraudster? Sometimes I think the only real difference is that the visionary is able to prevail through these periods where they’re faking it. And they’re able to keep getting money from investors so that they can get to the “making it” stage. And then nobody ever investigates to say, “Yeah, yeah, but for this period of time, they were actually faking it.” When you look back to Enron, Enron had a division called Enron broadband, and that really was Netflix, ahead of its time. And sometimes I think: If Enron had been able to keep getting money from the markets, could Enron have been Netflix? And you look at the Theranos story: If it hadn’t been for The Wall Street Journal’s reporting, could Elizabeth Holmes eventually have created a device that works, and nobody would have investigated this period of time when she was faking it? I don’t know. It’s an interesting question.

Why didn’t anyone go to jail over the 2008 financial crisis?

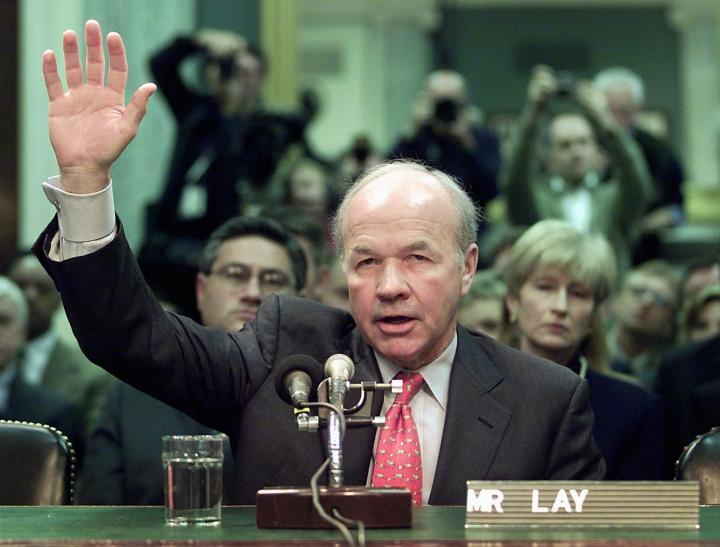

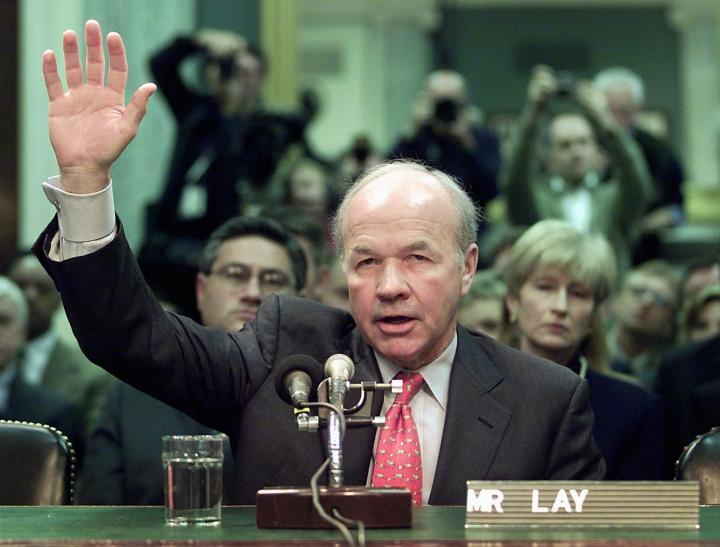

Brancaccio: [Enron’s] CFO, Andrew Fastow, went to jail. Enron’s former CEO, Jeffrey Skilling, went to jail. The former CEO and Chairman, Ken Lay, was awaiting sentencing when he died. We didn’t get to see similar scenes play out, people going to jail, after the mortgage crisis that came seven or so years after Enron. Is it apples and oranges, two different types of disaster?

McLean: No, I actually think it’s apples and apples. I think the line between what happened at Enron and what happened in the global financial crisis is much blurrier than people might think. Both were examples of lots of people manipulating the rules and figuring out how to make money for themselves out of something that was pretty much destined to collapse and leave economic wreckage for a lot of others in their wake. And both were, arguably, quite legal. There was just a different appetite for prosecution in the wake of Enron. I think one part of it is that what happened after Enron actively scared the Justice Department from prosecution because they did successfully prosecute Arthur Andersen, the big accounting firm. It went bankrupt; it destroyed tons of jobs. And people said, “Oh, wait, if we prosecute these big companies, then a lot of innocent people at these companies lose their jobs.”

Brancaccio: So maybe Enron was the last of a breed where people go to jail if the company’s big enough?

McLean: I worry that it was. I think that justice is not equal. A lot of it depends on time and place and the appetite for going after things. You’d like to believe that, when something goes wrong, the people who did bad things would pay the price for it, but I don’t think that’s the way it works.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.