Improving the restaurant industry could mean higher prices for diners

Improving the restaurant industry could mean higher prices for diners

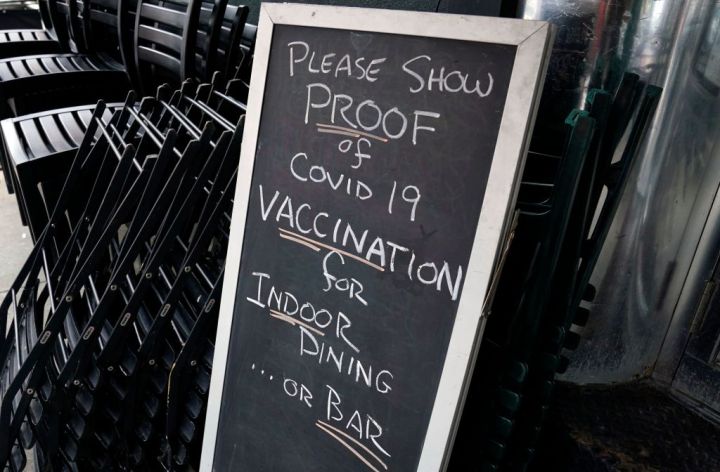

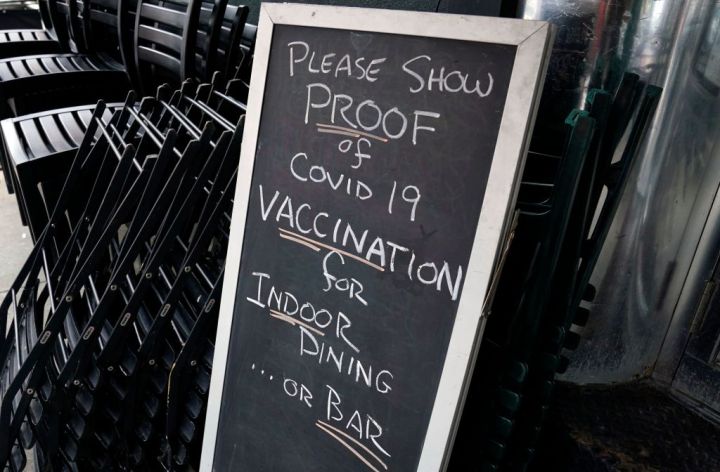

The restaurant sector has been dealing with a “reckoning” of sorts due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed the problematic nature of operating a restaurant on tight margins, cheaper ingredients and cheaper labor. But Peter Hoffman, a chef and former owner of the farm-to-table restaurant Savoy, believes this reckoning within the industry has been coming for some time. His new book “What’s Good? A Memoir in Fourteen Ingredients” explores, in part, how the restaurant sector got here.

“Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio spoke with Hoffman about how improving the industry could lead to a more expensive dining experience for customers. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Peter Hoffman: You know, it’s not just about raising wages, although that’s an important part, but it’s about a workplace that offers work life balance. Instead of being forced to work 60, 70 hours a week. And so we have to figure out how to make that possible. You know, one of the implications of it, David is, is that dinner is gonna cost more. And, you know, there’s a lot of pushback, obviously, we have limited budgets. But my experience being a farm-to-table chef and my journey to educate my customers over decades of running Savoy was that when we showed them what the real cost of food was, that is, if you don’t externalize costs and push them on to future generations, or push them onto taxpayers because they’re paying for health care from diet related diseases, people embrace that and want to pay more for dinner. They want to participate in a better world and a better planet.

David Brancaccio: So one of two things happens if you have an enlightened restaurateur, who wants to give flexibility, make sure that the work is not as grueling as it typically used to be, and to pay more. Prices would go up, you want the patron to actually be willing to pay the extra. And in some cases, the patrons may not be as enlightened as you want them to be. And that could be a moment of reckoning for a certain kind of restaurant.

Hoffman: There may be fallout from all of that. And, you know, when I grew up dining out was a was a special occasion, it wasn’t something that people did every day of the week in their lives. And we’ve gotten to the place, and part of that has to do with lowering the cost, that people could not cook at home at all and live their entire lives in restaurants. And so I’m not sure that’s been healthy for the economy. And, and that’s part of the reckoning that we’re seeing now. So when we completely outsource our dietary needs, we’re very dependent. And of course, you know, there’s a huge proliferation of restaurants that that has come with it.

Brancaccio: The fancy restaurants are gonna do fine, right? And I assume publicly held restaurant chains like Chipotle are, you know, probably gonna do alright. But you’re worried about a distinctive place that’s in the middle.

Hoffman: Yeah. And we see it in so many other parts of the economy and movement in our culture is that the high end will retain and possibly expand but they’re immune to these changes. And then the middle is dropping out, the middle class is dropping out, and so that in this case, what you have are more and more of faster food, fast casual. Even if they are about better for you or better for the planet kinds of concepts, which is good – it’s sort of farm to table trickle down – but at the end of the day, the restaurant that Susan, my wife and I built and started, which was a, you know, a more artistic, individual artistic expression of a exploration of cuisine, those places are going to be harder and harder to maintain and to be profitable.

Brancaccio: You’re not predicting they can’t survive. But the big open question is, if you pay people more, and if you give them more flexibility, which potential restaurant employees will be increasingly demanding after the pandemic, the question is, will the diners pay for the difference? That’s the question.

Hoffman: Yeah. Will they appreciate the fact that that’s an important aspect? Or will we come to acclimate that that is what the cost is. Plenty of businesses, right, large companies have all kinds of perks that they offer their employees that’s built in. Everybody understands that health care plans are part of large company offerings. Not that they haven’t come under pressure, when contracts get reevaluated and things like that over the years because of the high cost of health care. But still, they’re part of what the company model is. It’s not part of the restaurant company model for the most part. And so we trade on as diners, we want cheap meals, instead of saying we want a quality experience and this is what the real cost of dinner is.

“The reckoning is a good reckoning.”

Brancaccio: And from the potential restaurant employees point of view, there is a, what is seen as a shortage of workers in many parts of the economy. And it might be that the person who says, ‘I don’t know if I want to do those hours for that pay at the restaurant. When I can get a job working from home for an insurance company that has better benefits.’

Hoffman: Precisely and given the fact that we’re still struggling with the pandemic, by definition, it’s not a safe workplace, right? Or not as safe as some others. Restaurants don’t have the opportunity to work from home. Kitchens are by design, particularly in urban areas, kitchens are tight and people are working closely together and they’re interacting with all kinds of strangers in close quarters, without any knowledge of their behaviors. And so, people are reluctant to go back into restaurants, I get it. And as we said, it’s grueling work. It’s not always a positive work environment to be in. It’s a business that is being forced and it’s – the reckoning is a good reckoning. I love the restaurant business. I loved being in it, and I want it to be a healthy work environment rather than one that burns people out and casts them aside.

Brancaccio: So maybe we should brace ourselves for one of our favorite restaurants down the street that you know, wasn’t a chain place but wasn’t a one star fancy place. You know, you wonder how long they’ll be able to stick around.

Hoffman: Yeah, or brace yourself for the fact that you want them to stick around and so you’re prepared to pay more for dinner.

Food is best when it’s seasonal, transitional and ephemeral

Brancaccio: Let’s turn to a separate topic, specialized food. When people want what used to be rare and hard to find, or only available in a certain season for a certain moment in a year, you know, what do you want from people? If it’s good enough for you, as a chef, it should be good enough for me. But that has consequences and you’ve thought about those consequences?

Hoffman: Yeah. There are multiple chapters in my book where I tell the story of our journey in wanting to produce ubiquity in the food supply and the dangers of that, one of them is the chapter about strawberries. They’re highly perishable and very seasonal. So the journey for hundreds of years, actually, but really, in the late 20th century did it get quite serious was to say, how can we turn this food into a year round fruit so that it can be available all the time, across the nation? What’s sad about it is, is that what we traded away was flavor in order to have increase shelf life so that trucking times across the country could increase and things like that. That’s what the title of my book is about. And we’re saying, well, what’s good? What’s good is to say that something is here now, and is going to pass and it’s transitory. And I love it when it comes into season. And I actually love saying goodbye to it. Because it reminds us of the ephemeral nature of life as opposed to trying to think that we’re masters of the universe and can have anything that we want, any time of the year.

Brancaccio: It’s amazing the degree to which we’ve lost this idea of seasons, when it comes to food. This weekend, I went to three places – probably burned some gasoline doing so – looking for a pomegranate for this rice salad I wanted to do. Then I got home and was reminded that the reason I couldn’t find a pomegranate is it’s out of season, and I never even began to consider when is the best time to get a pomegranate. That’s the sort of thinking you argue in that book needs to change?

Hoffman: That’s right. And that it’s not just this self indulgent, I want to, you know, live this artistic life of living by the seasons. But I’m here in New York City and in fact, living by the seasons has real implications for our entire society. It’s a healthy way to live.

Brancaccio: But also your argument extends to bespoke artists and all things that we’ve come to expect will just be everywhere. That’s even more than a seasonal issue?

Hoffman: Yeah, Dr. Seuss in the Lorax talked about “biggering” and the danger of ever wanting to bigger and bigger and I think that that’s some of what we’re looking at. And looking at the climate crisis, climate collapse, so much of that is is about wanting more all the time, biggering as it were, instead of saying, what grows here, what grows in my region I’m going to try and live off of. Which is not to say that I’m anti-global, I mean, I drink coffee and like lemons and olive oil and things like that they don’t grow in this region. But if I was more limited in those choices, maybe that is a way of living more within our means, as opposed to living so far beyond our means that we are really in the process of destroying the planet.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.