The complicated history of voting technology

The complicated history of voting technology

The relationship between technology and voting goes way back to the late 1800s, when automated, hand-lever voting booths were introduced to help make vote counts go quicker and make voting more secure.

“I think a good argument can be made [that they] actually helped to achieve a certain degree of increased honesty in elections,” said Charles Stewart III, political science professor at MIT, in an interview with “Marketplace Morning Report” host David Brancaccio.

“The things were big beasts, they weighed 800 pounds, so you know, you’re not going to easily steal them,” said Stewart, who also founded MIT’s Election Data and Science Lab. “The machines were actually, and I think rightfully so, seen as bringing a bit of kind of business practice and a bit of kind of greater control and honesty in the vote-counting process.”

In recent history, however, fears of ballot box stealing have been replaced with fears of potential cyberattacks and other issues linked to technology. In what ways could the interaction between voting and technology change in relation to these kinds of worries?

Below is an edited transcript of Brancaccio’s interview with Stewart about the history of voting technology and where it’s likely to go in the near future.

David Brancaccio: I was surprised to see the first voting machines really go back to the late 19th century. We’ve been doing it that long?

Charles Stewart: Oh, yeah, they arose in the late 19th century. You know, there are periods in American history where technology is all the rage. And I think the rush to automate industry caught the idea of reformers, so we got automation in voting about 150 years ago.

Using voting machines to preserve election integrity

Brancaccio: Those machines could even tabulate back then?

Stewart: Oh, they could. They were great pieces of machinery. It was very similar to the same technology that was used in cash registers, that later we would see even in odometers and in automobiles. The technology was roughly the same for about 80 years, where you would indicate your choice by pulling down the lever next to a name. You’d have a curtain drawn around you while you were voting and then when you were done, you would just pull a lever. And so at the end of the night, all the election officials would need to do is pop the back of the machine off and write down the numbers that were on the counters.

Brancaccio: And some of this was the idea of modernity. But also some of this was, they thought those machines might help mitigate fraud at some level.

Stewart: Oh, absolutely. And, in fact, I think a good argument can be made, actually helped to achieve a certain degree of increased honesty in elections. The things were big beasts, you know, they weighed 800 pounds. So, you know, you’re not going to easily steal them. If someone crumbles up the piece of paper with the returns written on them, you can go back to the machine. It also made it easier for cities to have more voting sites. One of the problems in the 1890s and ’80s was that voting sites were so crowded, and automation facilitated kind of distributing out the voting so that the precincts were smaller, easier to control in terms of the crowd. And so, you know, faster recording of the vote, harder to steal, harder to make mistakes on the ballots. And so the machines were actually, and I think rightfully so, seen as bringing a bit of kind of business practices and a bit of kind of greater control and honesty in the vote-counting process.

The move back to paper ballots

Brancaccio: Now, in our current generation, we’re faced with this, I guess, it’s almost a paradox, right? In a world that’s getting rid of paper and embracing information on screens, the move for America’s voting system has really been back to paper and ink. And it’s on purpose, right?

Stewart: Oh, it has been and it’s very interesting as somebody who has gotten into history of technology by looking at voting machines. You know, a century after the mechanical lever machines came into view, the types of problems that election reformers worried about became very, very different. You know, we’re not as worried as we once were with crowds overwhelming a precinct and stealing the ballot box, for instance. We’re much more aware of ways in which computerized equipment can break down. We’re concerned with hacking and the rest. And so, you know, now, among kind of experts in the field, there’s greater interest in going back to paper, at least for the marking of the ballots. We’re still tabulating using automation — in this case, computers — but we have much better record now of what a voter intended to do in the event the equipment breaks down. Which, of course, we didn’t have with the mechanical lever machines, right? When you pull the lever back, all evidence about what you, an individual voter did, disappeared. So if the programming of that machine was bad, you couldn’t recover. If the programming of a computer is bad, you can’t recover. And that’s why it’s nice to have individual paper ballots as a backup.

Brancaccio: And, people don’t often reflect on this, but there is a way to do voting, and we were doing it for a while in a lot of places, where you press the electronic button, and you hope the vote gets recorded. But, in a sense, if it’s not recorded, you never know. And that’s why there’s been this move, in the past 20 years to, you know, have some kind of audit trail.

Stewart: Oh, absolutely. There’s a number of people who are worried, concerned about hacking and all of that. But I think the bigger concern, empirically, is just mistakes. And, as you say, you know, you push the button and you just don’t know if the vote has been recorded, nor can anyone even prove that anyone’s vote was actually recorded properly. There’s a lot of things that happen — you know, programming errors, the miscalibration of a touchscreen — and so being able, at the end of the day, to audit a system to demonstrate that the computerized tally equals, or is consistent with, at least, the paper ballots that are also evidence, can really assure election officials, the public that the election was handled properly.

Managing the broader voting system, beyond the ballots, with IT

Brancaccio: And, you know, we need to remind ourselves — you don’t, but I have to remind myself — a voting system goes beyond the recording of the voters’ choices and the scanning part of that. There’s a lot of storage, distribution, networking. That’s where you’re, I would imagine, you’re seeing more innovation than on the actual front end, which tends to look still, these days, pretty clunky.

Stewart: That’s right. What the voters generally don’t see is the increasing use of information technology to manage the broader voting system. Starting with voter registration, handling, not only the initial registration, but when people move, making sure that addresses are up to date. You need up-to-date addresses to make sure that people are assigned to the proper precinct and are given the proper ballot. And so that involves the use of geographic information systems, software to help manage the ballots that people get. As I said, you had the computerize voter registration systems not only keep track of the voters, but on Election Day they produce poll books that voters interact with and poll workers interact with to make sure that the proper people are voting and voting in the right place. And then, you know, after Election Day is over and the votes have been tallied, there’s a very large computer network that helps to aggregate all of those tallies, and to communicate them, at least unofficial tallies, to the press, to state election authorities, etc. Voting would be very different in the United States without the use of computing technologies, much like all of public policy, and actually all of our commercial lives, would be very different without the use of information technology to create the networks to do all of the transactions and allow us to do almost everything we do hundreds of times every day.

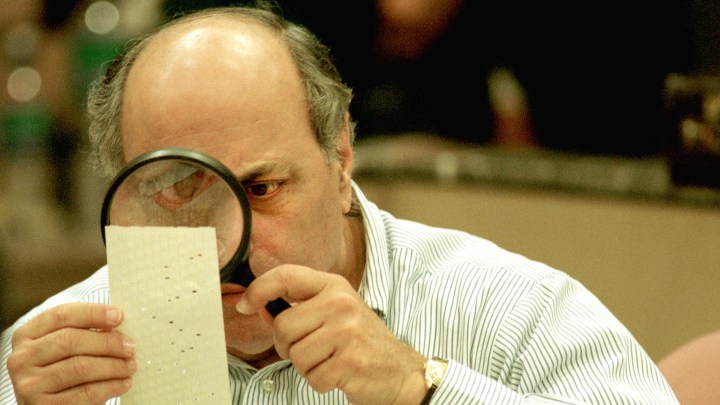

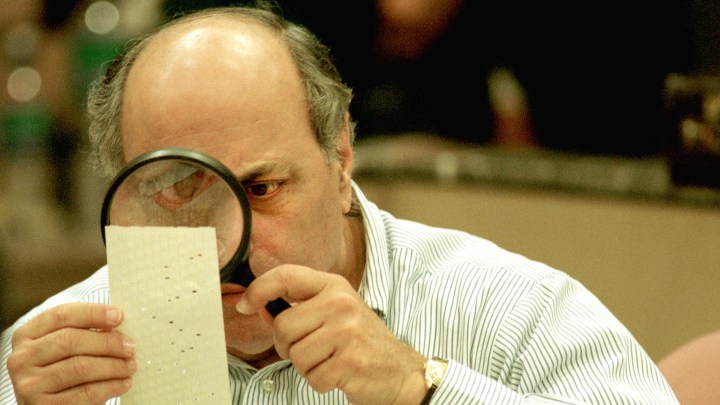

What issue could be the “hanging chads” of the 2020 election?

Brancaccio: Before we go, I got to ask: Is 2020, this election — are we finally post-chad, those little rectangles of ballot paper that voters poked out with the stylus? Or are chads still going to play a role in this election?

Stewart: Well, chads will not literally so, although I have one of these machines in my office and I still have to clean up after it every now and then. The closest thing to chad in this election would be, I think, the possible malfunctioning of an electronic voting machine that did not have a paper trail to it. There are still some of those machines left, between 5% and 10% of voters will be voting on those machines. Fortunately, they’re used in almost none of the battleground states. But, you could imagine, you know, a race for a county commissioner or maybe even for a state legislator, on the off chance there was a serious malfunction of a voting machine, it could happen. But those sorts of malfunctions have been pretty rare. And I doubt we’re going to see it implicated in the count of the presidential vote. I’m sure there will be other controversies around the count of the presidential vote, but I’m betting that they won’t be around the functioning of the voting machines.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.