A working man’s poet

This piece was originally published in April 2009. We’re bringing it back today having learned that 6.6 million people filed for unemployment last week, in addition to the 3.3 million that filed the week before. Ten million people are now out of jobs due to the economic shutdown brought on by COVID-19.

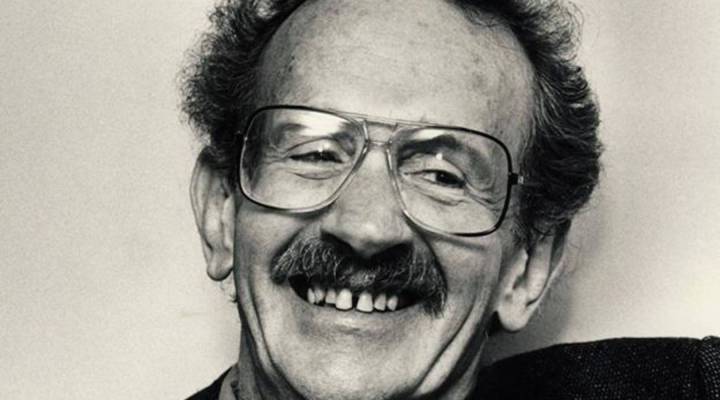

Those jobs bring income and stability. For a lot of people, they also provide a sense of self-worth. Poet Laureate Philip Levine died in 2015.

April is National Poetry Month. So for the next couple of Mondays we’re going to be looking at and listening to the poetry of all things economic. Money and work, commerce and labor, almost anything you can attach a value to.

Philip Levine grew up in industrial Detroit. He worked on the assembly lines at General Motors as a young man. His experiences there fed a lifetime of writing about the blue-collar economy. And when we spoke, I asked him to read one of his poems about not getting a job. So here’s Philip Levine and “What Work Is.”

We stand in the rain in a long line

waiting at Ford Highland Park. For work.

You know what work is — if you’re

old enough to read this you know what

work is, although you may not do it.

Forget you. This is about waiting,

shifting from one foot to another.

Feeling the light rain falling like mist

into your hair, blurring your vision

until you think you see your own brother

ahead of you, maybe ten places.

You rub your glasses with your fingers,

and of course it’s someone else’s brother,

narrower across the shoulders than

yours but with the same sad slouch, the grin

that does not hide the stubbornness,

the sad refusal to give in to

rain, to the hours wasted waiting,

to the knowledge that somewhere ahead

a man is waiting who will say, “No,

we’re not hiring today,” for any

reason he wants. You love your brother

now suddenly you can hardly stand

the love flooding you for your brother,

who’s not beside you or behind or

ahead because he’s home trying to

sleep off a miserable night shift

at Cadillac so he can get up

before noon to study his German.

Works eight hours a night so he can sing

Wagner, the opera you hate most,

the worst music ever invented.

How long has it been since you told him

you loved him, held his wide shoulders,

opened your eyes wide and said those words,

and maybe kissed his cheek? You’ve never

done something so simple, so obvious,

not because you’re too young or too dumb,

not because you’re jealous or even mean

or incapable of crying in

the presence of another man, no,

just because you don’t know what work is.

Ryssdal: You start this poem, the second or third line you say, “you know what work is, if you’re old enough to read this, you know what work is, although you may not do it.” And then you end with “because you don’t know what work is.” What does that mean? How do you make that transition from knowing to not knowing in the sense of this poem.

Levine: Ah, that’s the poem. If you’d listen to the poem carefully, you’d know the answer. Yeah, you know what work is abstractly. Right. I say to you, “Hey, do you know what work is?” Sure. But do you really know what work is? Especially this kind of work. No you don’t know what it is. It’s not an abstraction for people working on the line, let me tell you.

Ryssdal: What do you think of now when you read the problems that GM and Chrysler are having and then the problems that that is causing for all the folks who having been working for those companies for 35 or 40 years.

Levine: It’s heartbreaking. It’s heartbreaking. I mean, because there was a myth, of course, that these companies could never perish. And that their promises would be made good. Right now, I’m an older guy, you know, I’m 81. And what would happen to me if I lost my pension from the California State University system and Social Security. I mean I’d be out on the streets like these people might be.

Ryssdal: What is it about good, solid, difficult blue-collar work that so resonates?

Levine: I suppose it’s like reading about the Napoleonic Campaigns. It’s so far from most people’s experience, that is, people who do a lot of reading. It has a reality to it. It has a power because of that. At the time that I was doing it, I thought this will prevent me from becoming a poet. I will never have the time or the energy to write poetry because it was sapping to me to such a degree. And later on, when I was in my 40s, I realized, no Phil, that was the school you went to. And my whole attitude toward those years changed, so there was a way in which I realized that I had had an irreplaceable experience of brotherhood and sisterhood in those years that I was an industrial worker. And I wouldn’t give them up for anything.

“What Work Is,” from WHAT WORK IS, by Philip Levine, copyright © 1992. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.