“State of emergency” isn’t as alarming as it sounds

“State of emergency” isn’t as alarming as it sounds

California, Florida and Washington have all declared states of emergency over the COVID-19 outbreak. That means different things in different states, but officials are stressing that although an emergency may sound alarming, the purpose of the declarations is to help get people and money to the frontlines as quickly as possible.

Cities, counties and states declare emergencies on a fairly regular basis for disasters like bad storms, fires and floods.

“Really, all it means is that the government entity declaring the state of emergency can waive regulations, and then seek resources from a higher level of government,” said Christopher Douglas, associate professor of economics at the University of Michigan-Flint.

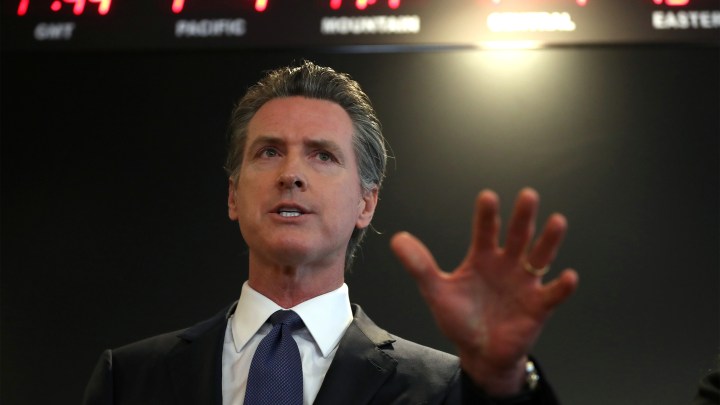

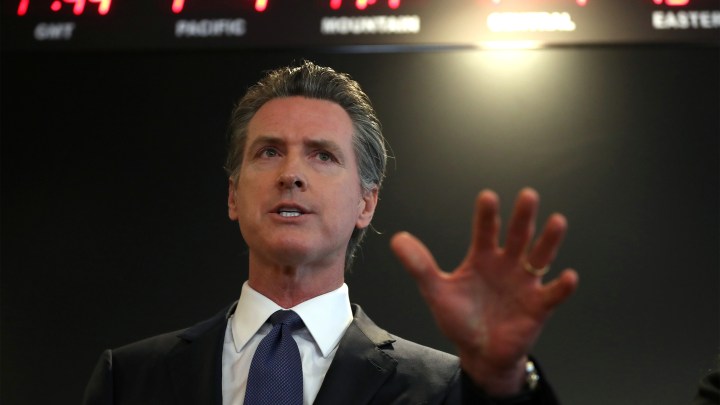

In California this week, Governor Gavin Newsom explained it also gives him power to curb things like unfair price hikes.

“We need to go after those that are price gouging not just for hand sanitizer, but for medical supplies and other equipment,” Newsom said.

Andy Baker-White, senior director of State Health Policy at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said what a state of emergency doesn’t mean is that people have to worry.

“I think that they should be reassured that the jurisdiction where they’re living is doing everything it can to respond to the coronavirus,” he said.

That could mean the freedom to bring in out-of-state medical staff, to use state property like fairgrounds in emergencies and to buy medical supplies with less red tape.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.