Why a mystery social media account on the U.S.-China trade talks is generating buzz

Why a mystery social media account on the U.S.-China trade talks is generating buzz

In the U.S., the press reports every twist and turn in the trade talks with the Chinese delegation, while the media in China remains tight-lipped on the subject.

However, a mysterious source of information has emerged in recent months that appears to have the inside track on the Chinese leadership’s thinking in the trade talks.

It has prompted China watchers to question who is behind it.

Chinese smartphone users can now subscribe to news and opinion articles about the trade dispute published on the widely used message app, WeChat, under an account called Taoran Notes.

One recent article includes an photo illustration of American and Chinese shipping containers crashing into each other.

The title of the article is: “Without sincerity, there is no point in coming for talks and nothing to talk about.”

In another article, Taoran Notes described a round of trade talks back in January in a way that caught the eye of Marketplace’s Shanghai bureau news assistant Charles Zhang.

“It’s this sentence that said [U.S. trade representative Robert] Lighthizer was very nervous and almost silent. Chinese vice premier Liu He had a natural facial expression,” Zhang said. “It means Liu He was more relaxed, maybe confident, even.”

Chinese citizens rarely get this kind of detail from their own state-run media, which is why Taoran Notes has created a buzz among China observers.

“Information tends to get people excited in China,” said David Bandurski, co-director of the China Media Project.

China’s news censorship

The Chinese Communist Party censors news and information, especially about U.S. tariffs. This leads to murky coverage on the trade dispute in the Chinese state-run media.

For example, President Donald Trump complained on Twitter earlier this month that trade talks with China were moving “too slowly” and that he was going to increase the tariff level on $200 billion worth of Chinese from 10% to 25%, with more tariffs to come.

The news was not widely circulated in China because Twitter is blocked in the country, like many foreign news web sites.

Mentions of President Trump’s tweets were scrubbed from China’s social media, while the Chinese state media ignored the news for much of the day until China’s foreign ministry commented on the issue.

However, rather than reporting that President Trump is raising tariffs again, Shanghai’s financial TV channel Yicai opened its evening broadcast as follows.

“On May 6, the foreign ministry spokesperson, Geng Shuang, held a press conference and a journalist asked about President Donald Trump’s statement to add additional tariffs on Chinese products,” said Yicai program host Li Ting.

She proceeded to read the foreign ministry’s response in full before abruptly returning to the day’s top news, which was that the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets slumped between 5.6% and 7%.

“Due to the impact of some external factor, the stock market in Shanghai and Shenzhen both had big drops today,” Li said.

She avoided linking the stock market slump directly to President Trump’s tariff threats.

Censorship expanding

Economic news is more regulated than ever before, which wasn’t always the case, said Bandurski.

State-run media editors may get a directive from the Chinese Communist Party on how to cover a topic or avoid sending a reporter to a breaking news story.

“Ten years ago this would still have left a huge gray area outside of what is explicitly prohibited,” Bandurski said.

For example, an environmental story could have interesting political elements.

“That has become very difficult to do under [Chinese President] Xi Jinping,” Bandurski said.

Small investors like Huang Shengjun have noticed the general quality of financial information downgrading. Huang says he doesn’t even trust research notes from economists.

“The China Securities Regulatory Commission held a meeting last year with chief economists from funds and brokerage firms. The meeting was called a seminar, but actually it was to tell chief economists to be careful of what they write,” he said.

After that meeting, the economists signed a pledge to “positively guide market expectations.”

Self-censorship

Self-censorship is a key part of information control under the Chinese Communist Party.

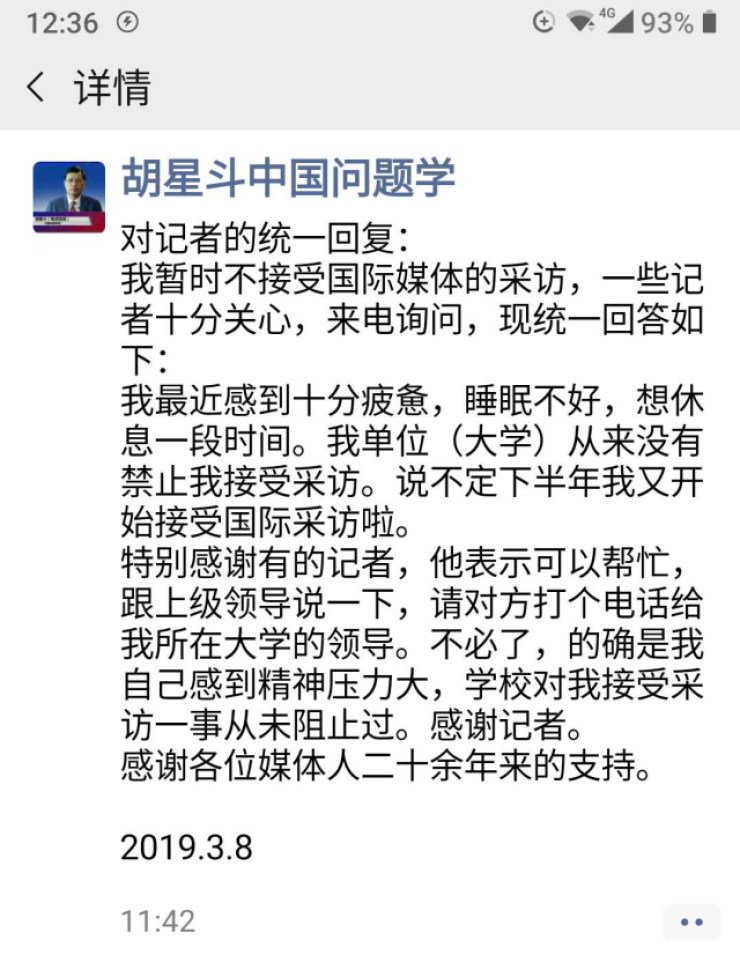

In March, an Beijing Institute of Technology economics professor, Hu Xingdou, published a statement on his social media account that he could no longer do interviews with the foreign media because he was “tired” and “didn’t rest well recently.”

Hu had previously spoken to Marketplace and was often quoted in the domestic Chinese and foreign press.

He added that turning down foreign media requests was his own decision and not a result of pressure from his university.

Marketplace has encountered more instances of interviewees in China withholding their full names out of fear of official retaliation since the tit-for-tat tariffs began.

This occurs even when the topic is neither political nor related to the trade dispute.

Given the heavy censorship environment, Taoran Notes’ existence is unique.

When President Trump made good on his threat to boost tariffs, it published an article that said: “If you want to talk, talk. If you want to fight, fight.”

Who is behind the Taoran Notes account?

Huang, the investor, has a theory on who might be behind Taoran Notes.

“Since its articles were reprinted by the official media, the account should be run by some editor-in-chief from a state news outlet, or at least someone with a government title,” he said.

Taoran Notes has not acknowledged whether it has state backing, but Chinese media analyst Bandurksi said there have been other social media accounts that were later revealed to be associated with a government ministry. He said the Communist Party has a dilemma.

“We have, under [President] Xi Jinping, controls to an extent we have not seen at any period in the reform era and yet, China is more enmeshed with the world. Its people demand real information, because this is the information on which they base investment and business and the future,” Bandurski said.

“Part of what we’re seeing with cases, even like this Taoran account, are maybe [China’s Communist party’s] experiments with new ways to put information out there without rocking the boat, or without really owning up to it.”

For anyone who wants to know the Communist Party’s official line on trade talks with the U.S., Bandurski advises sticking to the carefully curated People’s Daily newspaper edition.

“It’s always a good bellwether to see how China is thinking at the top,” he said. “But it’s not a perfect measure.”

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.