How the energy boom shaped a small town in rural America

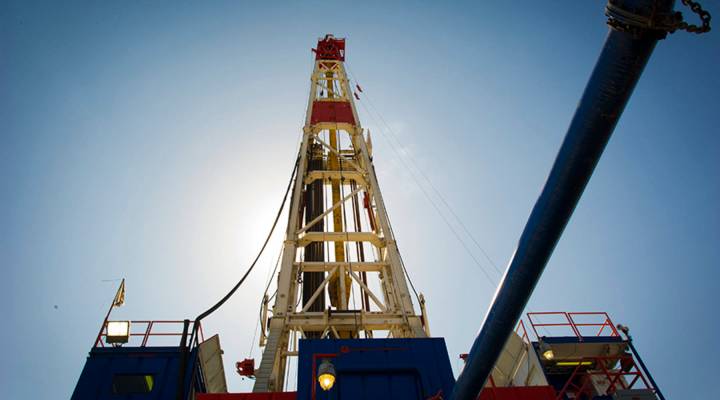

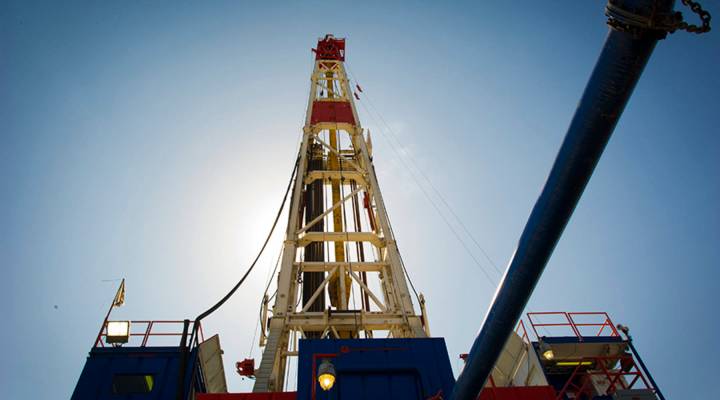

When a fracking company came to a small community in rural Pennsylvania, many people signed the lease that allowed the company to access the natural gas resources on their land. Among them was Stacey Haney, who at that time owned a small farm. Haney saw the lease as a way to support American energy, and like many other people, a way to get some extra money to support life. But money is not the only thing fracking brought to the town, and people like Haney ended up paying a price.

Marketplace host Kai Ryssdal talked to Eliza Griswold about her new book “Amity and Prosperity,” which delves into how the fracking company changed people’s lives in one rural Pennsylvania community. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: Before we actually get into the substance of this book I want you to tell me, and this is going to sound weird, but I want you to tell me about Cummins the puppy.

Eliza Griswold: So Commins the puppy belonged to Beth and John Voyles. And Beth Voyles, she thinks Cummins drank from a puddle of water that was contaminated by industrial waste. And that’s what made him sick, and eventually Cummins died.

Ryssdal: So now that we have Commins the puppy, I want you to tell me about Stacey Haney.

Griswold: So Stacey Haney is a single mom and she has for many years been a nurse, and she has a small farm … she had a small farmer. And she was living there pretty happily until 2010.

Ryssdal: You say she was happy until 2010 because in 2009, if I had my dates right, she signed a fracking lease?

Griswold: Yeah. So Stacey Haney, she was very proud to sign a lease when the oil and gas industry came about a little more than a decade ago to her area. First of all, she wanted to buy her dream barn, a barn that was going to cost about $9,000. But she was also proud to support America because she believed that American energy independence would help keep American soldiers out of foreign entanglements that involve oil. And she saw exploiting the energy that was on her land as part of an American solution.

Ryssdal: I want to point out here that this is a story, in part, anyway, of the terrible things that happened to Stacey Haney’s family — contaminated water is the least of them. The child gets horribly sick, the livestock — I mean, terrible, terrible things happen after she signs with Range Resources, the fracking company. But at the time she signed it, it was a good idea for her.

Griswold: It was a good idea. She is a pretty tough customer. She’s very smart. And for all she could see and hear, this was the right thing to do.

Ryssdal: You reported this story over like seven years or something, right?

Griswold: Yes.

Ryssdal: You got there sort of two years after she had signed the lease and after the fracking started. When you got there, what did it look like, smell like? Was there grimy dust in the air? I mean, what was it like?

Griswold: You know, what struck me most was just that this was a network of industrial sites. It’s some of the most beautiful country I have ever seen. And I have been all over the world. The frack sites can be hard to see. There often at the top of hills, which can make their water contamination even more of a concern because anything of that top of the hill is going to run down. But all of the industries surrounding, truck traffic waiting, getting stuck at behind water trucks that traveled at that point in caravans really for safety because that was better for them. It was just —

Ryssdal: There was —

Griswold: Yeah, go ahead.

Ryssdal: Sorry. There’s a great scene — it is not a scene, it’s like a sentence and a half in this book — talking about those water caravan trucks, and the first one goes through like a yellow light. And then the other, you know, 10, 12, 14, whatever it is keep on going. And so if you’re driving through Amity, because of these trucks, you get stuck.

Griswold: Exactly. And that’s the least of it. So one of the things that the book really tries to chronicle incredibly carefully and fairly are the hidden costs associated with industry. In some places, people love the oil and gas company that has come through and paved their roads. But how long does that paved road last, and what are the longer-term costs that Americans end up paying?

Ryssdal: There are, we have to say, people in Amity and Prosperity and in the surrounding townships, who were OK with the fracking company Range Resources and didn’t actually have a problem with it.

Griswold: More than OK. One of the first times I went to Amity, I went to meet a farmer, but he also, what he did day to day is he’s a barber. So this one barber said to me, you know, “Where are you from?” And I said, “I live in New York City, but I’m from Philadelphia.” And he said, “That’s two strikes against you.”

Ryssdal: [laughs] Yeah.

Griswold: And that conversation began for me a learning, which was why over so long have rural Americans felt increasingly disenfranchised and really enraged at urban Americans? And part of that has to do with people who are supportive of fracking, legitimately so, saying, “Listen, you guys are going to come in here and wag your fingers at us? This is the first opportunity we’ve had to make money off of our land in more than a century.”

Ryssdal: I don’t usually do this, but I want to go on the way out here, I want to go to the note on sources that you include in the back of this book, and I want to go to the very end. And the last two sentences of this book are: “This is the story of those Americans who’ve wrestled with the price their communities have long paid so the rest of us can plug in our phones. Some feel that price was worth paying, others don’t.”

Griswold: You want me to say anything.

Ryssdal: I don’t know, what do you say?

Griswold: I mean, what I hope this book does is fairly portray a place and a people who have been screwed by disparate interests for a very long time. And sometimes those voices can be hard to listen to, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t have to do it.

Click here to read an excerpt from the first two chapters of her book.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.