Campaigns don’t need a Cambridge Analytica to target you

It’s primary season, with voting in Idaho, Nebraska, Oregon and Pennsylvania on Tuesday and dozens more elections in the coming week to determine who will land on the ballot for November’s midterm elections.

But you can’t talk about elections these days without talking about voter data — how campaigns gather it, and how they use it. The scandal involving Cambridge Analytica, which created detailed profiles of voters by scraping their data, may dominate headlines. But that sort of research, even when it is gathered properly, is pretty far beyond what most campaigns can manage or afford.

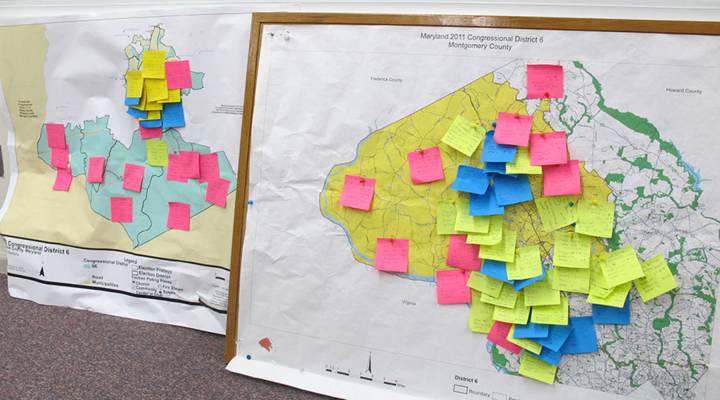

Nevertheless, even small campaigns are using technology to harness voter data. Republican Amie Hoeber, for instance, is a candidate for the House seat open in Maryland’s 6th District. She uses data to help her pinpoint specific homes in specific neighborhoods, where there might be voters receptive to her message.

“You want to know who are the regular voters? Who are the people that you want to make sure that you get them through mail, or phone call, or knocking on their door?” said Hoeber, a former undersecretary of the Army and business owner running in a Democratic district.

Republican primary candidate Amie Hoeber relies on data to help her small campaign target likely voters.

She gets that information from an app called Advantage, which gives her team a list of suggested homes to visit in one tree-lined suburban neighborhood in Rockville on a sunny spring day.

“The software that we use,” explained campaign field director Dan McHugh, “[gets] data for us on the voters that we’re trying to target, which right now is a lot of … Republicans, soft Democrats, [and] we are hitting some independents.”

The details that help create such lists often don’t come from some highly advanced data operation. It’s usually information from state or local election boards that is available to all candidates. David Nickerson, an associate professor at Temple University who studies data and elections, said it’s usually pretty basic.

“[Things] like name, age, gender,” said Nickerson, “and it has whether or not the person voted in each election, going back close to 20 years in most states.”

Whether someone voted, or their party registration, can be particularly helpful to candidates, said Nickerson. “It doesn’t make sense to knock on the doors and try to persuade them if people have never voted.”

Nickerson said these voter files tend to be relatively inexpensive for candidates at the local level, maybe $100-$150, but prices can vary widely. On top of the information from local election boards, candidates can also buy commercially available data sets that can include updated phone numbers, people’s shopping habits and other information that will better identify likely voters. Or they may get that data from their party or a national campaign committee.

“The best data available is coming from the national parties, who are in the business of giving it at a subsidized rate to the state party,” said Nickerson. The state parties then have the choice to share it with individual candidates.

Even without advanced data, the basic technology is good enough for even small campaigns with limited funds get pretty specific. Hoeber, the congressional candidate, for example, is confident enough in her data that she doesn’t even bother to leave campaign leaflets at homes not on her list, although she does chat with people she meets along the way.

As she goes from house to house, she coordinates with her field director, McHugh, to keep track of the responses she gets — enthusiastic, positive, negative, not home. All information that gets fed back into her campaign database.

“So it reinforces the validity of the database,” she said. “And so that again ensures that the right feedback gets into the database because it gets refined essentially every day.”

Every day up until primary day, which in Maryland is June 26.

| Cambridge Analytica, Facebook and the new data war |

| Mark Zuckerberg to Congress: My team will get back to you on that |

| Erasing your digital footprint is hard |

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.