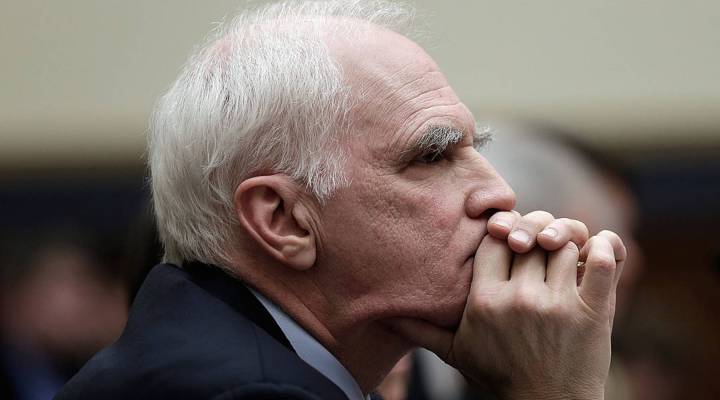

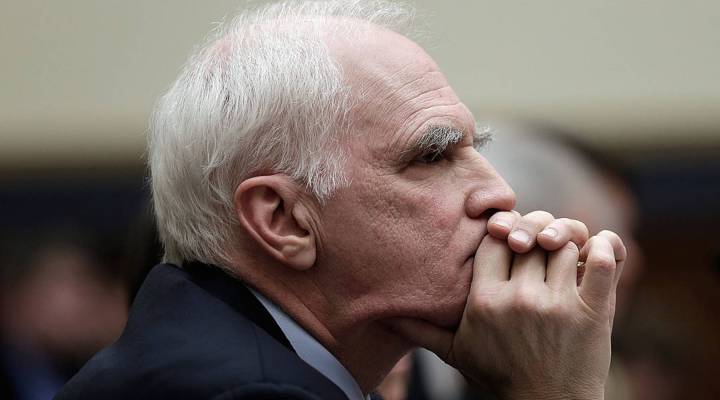

Outgoing Fed Gov. Daniel Tarullo says cyber security is top on his list

Outgoing Fed Gov. Daniel Tarullo says cyber security is top on his list

“Too big to fail,” “systemic risk,” “financial stability” — three phrases used when it comes to regulation of the financial system. But they’re also ideas that have been the primary focus of Federal Reserve Board Gov. Daniel Tarullo the past eight years.

Wednesday is Tarullo’s last day at the Fed, so Kai Ryssdal spoke with him for a look back at his time at the central bank.

Below is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: Why are you leaving now? Your term runs for another number of years.

Daniel Tarullo: Well, you know, Kai, I’ve been at the Fed for over eight years now. I came in with a group of people with the intention of trying to get a set of things done to make a safer and sounder financial system. And I think we’ve collectively made a lot of progress towards that end. And I think there just comes a point where everybody for their own purposes should probably move on and do something else. And I just felt it was the right time for me to do so.

Ryssdal: I’m going to put some words in your mouth here. But we’ll see how this goes. Are you declaring victory and departing the field on your regulatory goals when you join the Fed.

Tarullo: No, not at all. I mean, I think the dangers come when anybody declares victory, probably on any policy issue, but certainly in financial regulation. Because as you know, the financial system is a constantly adaptive one, and so regulation needs also to be adaptive. No, I just think we achieved a set of specific concrete goals that we wanted to achieve, particularly with respect to building up the capital and liquidity positions of our largest banks. And although there’s going to be a need to refine what’s been put in place and adapt those regulations over time, I did think this was a good point for me to leave.

- RELATED: What Trump territory thinks about the Fed — and raising interest rates

- A fully public Fed?

- Janet Yellen’s job explained in five questions

Ryssdal: You’re satisfied now, just to put it in the vernacular, that the big banks have enough money in the bank to weather another storm?

Tarullo: Well, I think that we have definitely strengthened the financial system substantially. You know, I think there might be an argument for a little bit higher capital requirements for the very biggest banks. But if you look at where we are today compared to where we were seven or eight or nine years ago, it’s just a much stronger financial system.

Ryssdal: I’ll tell you what, take me back then, would you, to early-ish 2009, when you joined the Fed. You walk in the door, and Ben Bernanke goes, “Oh, my god, am I glad to see you.” Right?

Tarullo: Well, sure. I think everybody was looking for help anywhere they could find it. And just to take your listeners back to late 2008 when we were in transition from the election to early 2009, remember what was happening at the time. I mean, Kai, you probably did programs where people were talking about whether the financial system needed to be nationalized. And so faced with the complete lack of confidence in the financial system, faced with the fact that we had had to inject taxpayer capital into all of our largest institutions, we had two jobs. The first was tried to restore public confidence in the financial system, and second, after we did that, was to try to make sure that we put the financial system on a footing where the risks of that kind of calamity would be much, much lower.

Ryssdal: Let me extend that then from the financial system, which you’re directly in charge of, to the economy writ large. Are we — economically, now, not financial system — but are we safer and better off now than we were in 2009?

Tarullo: Well certainly we’re better off than we were in 2009. I mean, again, our economy was hemorrhaging jobs. We were on the way to what turned out to be the deepest recession since the Great Depression. And obviously, we’re in a substantially better position than we were then. I think, though, that notwithstanding six or seven years of steady if unspectacular growth, we’re all still focused on the fact that we’re not achieving growth levels that existed in the economy even in the somewhat pre-crisis period. And we do have a question of inequality, which has been hanging over the economy for a long time. But I think people are focused on it more since the crisis.

Ryssdal: Well, so but here’s the thing. Just continuing in that thought, I mean we go out, I, personally, and our reporters obviously go out and do reporting trips. But I’ve been to Alabama and Oregon and all over this country. And people aren’t feeling the stability and the safety that the Fed, yourself here now, and Chair Yellen, certainly in her public remarks, is is talking about. What is that disconnect between actual people in the economy and what you all are doing?

Tarullo: Well, I think you know it’s difficult for any one of us to say with assurance why that’s the case, but let me just offer you at least one thought. I mean, you and I both know a lot of people who grew up in the Depression, and as we know, a lot of people who grew up in the Depression have had an attitude towards savings and towards economic stability and job security that was very much shaped by that period of their lives. And I suspect we’re seeing in somewhat lesser form a repeat of that. People are now aware of the fact that things can go badly wrong in the economy. And so there’s, I suspect, some lingering anxiety, which is not without foundation.

Ryssdal: Is it true that you had decided to step down from the Fed even before the election?

Tarullo: Yes, pretty much. In fact, a couple of years ago, I thought this was getting to be about enough. I had basically decided that it was about the right time to go and the spring would be about the right time.

Ryssdal: Do you have concerns, though, with what seems to be the deregulatory environment in Washington? Certainly members of Congress and some folks at the White House have talked about changing Dodd-Frank and doing what they can to loosen some of the restrictions on the financial sector.

Tarullo: Well, sure, I would have concerns about some directions that some of those impulses might go. But having said that, there are also some things which I think could command a pretty broad consensus across party lines of relaxing some of the restrictions on community banks, raising some of the Dodd-Frank thresholds for the size of banks that have to be covered by particular regulations. And again, it’s important to note that the most important thing for us to emphasize is the stability and the resiliency of our very largest institutions, because it’s those banks whose problems, whether idiosyncratic or systemic, can threaten to bring down the whole system.

Ryssdal: You’re going to give a speech tomorrow. It’s been billed as your farewell address at Princeton. I imagine you’re going to outline what you’d like to see happen with financial regulation in this country. Give us a quick sneak preview.

Tarullo: As you can imagine from our conversation, I’m going to emphasize the importance of capital and of keeping capital high, because that is a buffer against losses that may come from unexpected sources. You know, Kai, it’s not as if there’s not room for change in Dodd-Frank. There was never an opportunity to have a technical amendments bill to Dodd-Frank the way most major pieces of legislation have. So it’s not surprising there are things that could be changed. I just hope that people don’t rush into changing things without evidence and that people remember there was a reason why all these new regs were put in place, and that reason is those dramatic times in late 2008 or early 2009 that we were talking about.

Ryssdal: Let me get Rumsfeldian on you here for a minute. What is the unknown unknown in the financial sector that keeps you up at night as you leave?

Tarullo: Well, I would say, of course by definition, you don’t know the unknown, and so you just kind of have a generalized middle-of-the-night angst that you can’t totally pin down. There’s always the possibility, right, of the creation of new asset classes with new funding vulnerabilities that over time turns out to be problematic.

Ryssdal: So wait, let me let me ask you actually about that. In other words it’s Wall Street creativity, right? New asset classes, things that Wall Street innovates and says, “Hey, this is a great new idea.”

Tarullo: Right, subprime securitization, you know, in its new avatar. Of course, we can’t say it won’t happen. But there, I think, the oversight and monitoring processes that the Fed and the Treasury Department, and for that matter, a lot of private academic economists, have put in place, will at least help draw our attention to those things. So I think when you talk about the unknown unknown, I think we probably need to worry about operational risks, cyber security risks, and I would put cyber right at the top of my list of concerns. Because that is a different kind of world and one in which our regulators and supervisors don’t have as much experience with as they do with overseeing sound underwriting practices for lending, for example.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.