What it’s like to walk away from a house

Tess Vigeland: We talked earlier with a couple who decided not to walk away from their mortgage despite owing more than their property is worth. But for tens of thousands of people the American Dream of home ownership ended when they handed the keys over to the bank — and said goodbye. There have been dire warnings about financial lives crashing and burning for years on end after home owners walk away. We wondered what the reality looks like.

SOUND OF GUITAR

Jon Wittenberg: I’m gonna play you something that’s appropriate to the occasion.

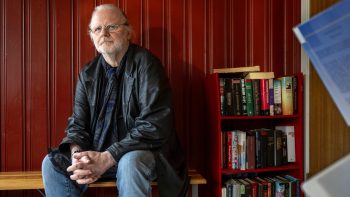

Jon Wittenberg is 42 years old. He walked away from his condo a year and a half ago.

Wittenberg: A little Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: “This old house of ours is built on dreams. And a businessman don’t know what that means. There’s a garden outside she works in every day. And tomorrow morning, the man from the bank’s gonna come and take it all away.”

In the middle part of the last decade, the pharmaceutical company Wittenberg worked for moved him from Boulder, Colo., to Agoura Hills, Calif.

Wittenberg: There was a lot of pressure at the time to buy houses in Southern California. Everybody was making tons of money. And my company had a relocation expert who said to me, “I’m almost going to have to insist that you buy a property.” So I did. I bought a fixer-upper for $450,000 in April of 2006.

Wittenberg put 20 percent down on a 30-year fixed mortgage — and spruced up the two-story condo himself. A year and a half later, he was laid off. He got a new job with a renewable-energy company in San Francisco. So he turned the condo into a rental and headed north. But tenants kept demanding lower and lower rents, until he had a shortfall of more than $1,000 between the rental income and his mortgage payment. And by 2009, comparable homes in Agoura were selling for almost $100,000 less than what he owed on the property. He tried to get the bank to modify his loan, to no avail. So with the help of a company called YouWalkAway.com, he stopped paying his mortgage.

Wittenberg: We looked at how much my home was underwater, how much money I’ve lost thus far, and how much money I will continue to lose until I start to break even. That could be 20 years away, I mean it’s not going to recover that quickly. It was a no-brainer. It became a business decision.

YouWalkAway.com’s Chief Executive Jon Maddux says that’s how it should be — a no-brainer — for the 11 million people who are underwater on their mortgages.

Jon Maddux: A lot of our clients are people who have never been late on anything in their life. And now it’s this massive thing that they’re going to default on and it goes against everything they’ve ever known. But I think as more and more people know someone that’s done it, it’s something that people are accepting.

Jon Wittenberg knew that a default on his home loan could spell doom for his credit score, which he says was in the low-to-mid 700s. The bigger question was: What would happen to the rest of his financial life?

Wittenberg: Am I gonna have to pay this back? What are these banks capable of doing to me? So here I am — I’m probably upper-middle class, I have two degrees and here I am, I’m stuck.

He won’t have to pay it back — because California is what’s called a “non-recourse state.” The bank cannot come after mortgage holders when they walk away. As for his credit score? Fair Isaac released a study earlier this year showing the average FICO score drops around 100 points in a foreclosure, which is how walkaways are classified.

The bigger surprise, according to YouWalkAway.com, is that many of its clients are finding their scores begin to recover within a few months. The impact so far for Wittenberg? Well, there hasn’t been any. He lives in his girlfriend’s house north of San Francisco. So he didn’t have to worry about a landlord checking his credit. And he says he’s done with debt forever.

Wittenberg: I don’t have a credit card. I don’t have a car payment. I don’t have anything. I live in a cash world, and I want to keep it that way.

That’s not to say he hasn’t paid a price. He lost his entire down payment and drained a significant portion of his savings account to make up for that monthly rental shortfall. But he hasn’t checked his FICO score — and he doesn’t want or intend to. What saddens him most is the loss of the condo he would have held onto, but for the math.

Wittenberg: There is a pride of ownership. It’s nice to own your own castle.

And it may be quite some time before he is a king again.

Bill Sawyer: OK, so I’m doing my FICO score.

Six hundred miles north in the rural community of Wilsonville, Ore., 50-year-old Bill Sawyer sits at a laptop in his apartment, punching in his Social Security number at MyFico.com.

Sawyer: OK, so we gotta type in a profile here.

Vigeland: I promise I won’t watch your Social Security number.

Sawyer: OK. You can take my credit if you like. Don’t know if you’d want my identity.

Last he knew, as of a couple of years ago, his credit score was in the low 700s. But that was before he walked away from a small townhouse in nearby West Linn. He bought it a decade ago for $138,000. Over the next few years, its appraised value nearly doubled. And the bank let him borrow money twice against the house.

Sawyer: They just crunched the numbers like a car salesman might. And, you know, you sign the dotted line and this is what I need to pay every month and this is what I get.

Sawyer, who works as an operations and policy analyst for the state, used the money to pay down other debts — including credit cards and a car loan.

Then in 2007, tragedy struck. His 18-year-old son Daniel was killed in an auto accident. Aside from the emotional and psychological devastation, the accident sent Bill Sawyer into a financial tailspin.

Sawyer: There were some financial hardships that kind of started a chain reaction, you know, with a maxed-out credit card and a line of credit through my bank. When you have a limited income, and you make minimum payments, well that debt just keeps going.

Then, on top of everything, the housing market collapsed. And he owed more than his home was worth. He tried to negotiate for a loan modification. After that fruitless effort, he abandoned the property in March of this year — also with the help of YouWalkAway. But he had not wanted to check what that has done to his credit scores.

Sawyer: I’m holding on tight. Oh my gosh. Never has it been that low. TransUnion 535. Equifax 520.

Vigeland: Are you surprised?

Sawyer: I’m not shocked by it, no. You know, but it hurts. You work your whole life establishing a reputation with your credit. Pretty much start over from the bottom of the barrel now.

It’s not the bottom of the barrel, but it is close. And it was made worse by a bankruptcy filing over the summer. Sawyer made sure to get his current apartment before moving out of the townhouse just in case landlords were scared away by a low score. But if he ever has to move, he knows the walk-away could make everything more difficult. For now, he feels relief.

Sawyer: We were happy in that home. I didn’t see any other way to resolve this matter without pretty much putting money down the drain for years to come. I made the decision.

And it was the best decision, he says, for him and his 23-year-old daughter Vanessa — who lives with Sawyer. His financial recovery appears to have started already. Sawyer was approved last month for a $300-limit credit card through Capital One, which he plans to pay off each month in an effort to repair his score.

Sawyer: I’m not looking to buy another house. Probably ever. I’m going to live within my means and kind of start from scratch.

They key is that he was able to start from scratch.

There’s a lot happening in the world. Through it all, Marketplace is here for you.

You rely on Marketplace to break down the world’s events and tell you how it affects you in a fact-based, approachable way. We rely on your financial support to keep making that possible.

Your donation today powers the independent journalism that you rely on. For just $5/month, you can help sustain Marketplace so we can keep reporting on the things that matter to you.